In this exclusive extract from chapter 6 of The Eurasian Steppe, author and archaeologist Warwick Ball explores the material culture of the nomadic Scythians, a cultural group that flourished in the Eurasian Steppe in the first millennium BC.

What has made Scythian art so distinctive is that the vast majority of surviving objects are of gold, and of a gold of beautiful quality and frequently of excellent craftsmanship.

– Esther Jacobseni

Being nomadic for so much of their history, the Scythians have naturally left few material traces in terms of settlement: no great cities, temples, or palaces. There is one fixed abode, however, which even nomads cannot do without: their burials. These are known as kurgans in Russian (a Turkish loan word) or mogila in Ukrainian: underground burial chambers, often constructed of wood, covered by high mounds of earth, whose distinctive silhouettes are often the only relief on the otherwise flat Eurasian steppe.

But it is not the architecture for which these kurgans are renowned so much as their contents.ii Many of the Scythian elite were buried with a vast array of treasures: gold vessels, weapons, felts, carpets and other textiles, as well as items of everyday use. Fabulous treasures from nomad tombs have been found not only in Ukraine and Russia, but also in Thrace, Bulgaria, Iran, Siberia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and China.

Scythian Gold

Esther Jacobsen rightly emphasises the importance of gold in Scythian art in the quotation above, further emphasising that more gold art has survived among the Scythians than from most other ancient cultures. This is partly because gold is immutable so can survive in perfect form, but the same is true of, for example, Persian or Syrian gold, which has not survived in anywhere near the same quantity. This may be because of gold’s intrinsic value, hence its being more prone to recycling and looting in antiquity. Its intrinsic value also perhaps makes it more prone to study, the fascination for gold being universal. But the same can be said of Scythian gold. The point that Jacobsen makes is that it has been plundered: in by far the majority of excavated kurgans the contents have been looted, usually in antiquity. What we see now of Scythian gold must, therefore, represent a tiny fraction of the amount of Scythian works of art and craftsmanship that originally existed: ‘There is no doubt that the vast majority of what was originally made for the Scythians has been lost … and … object types we now know only through one or two examples may have originally referred to a substantial number.’iii

Legendary Scythian Gold

Herodotus recounts the foundation legends of the Scythians north of the Black Sea. These tell of four gold objects that fell to earth from heaven: a cup, a sword, a yoke and a plough. Accordingly, gold was, in effect, worshipped by the Scythians for its own sake rather than for its intrinsic value as an exchange commodity. This receives added support when we observe that even many wooden or bone objects were coated in gold leaf to simulate gold. Hence, the Scythian tribes would hold an annual gold festival.iv This is confirmed by the quantities of gold found in Scythian tombs, evidence not so much of wealth – nomads would have little need of a cash economy – but of the sacred nature of gold. There is emphasis on gold bowls, representing heaven; swords too are given prominence, although it must be admitted that ploughs are generally conspicuous by their absence.

Transportable Wealth

There is another reason why gold features so largely: it is the easiest of metals for a nomad to procure and handle. Gold is rare, found only in small quantities in specific localities that might be far distant from one’s base. For nomads, this is less of a problem; migrating vast distances is their way of life and they would have had access to sources of gold that might be many thousands of miles away – through inter-tribal exchange or raids across the steppes, if not directly. These sources, usually alluvial gold in mountain streams, are furthermore easy to tap by simple panning and similar methods, without the sophisticated mining for copper or iron that requires a sedentary population. The mountains on the fringes of the Scythian world, the Urals, the Caucasus and the Altai, are moreover all gold-bearing.

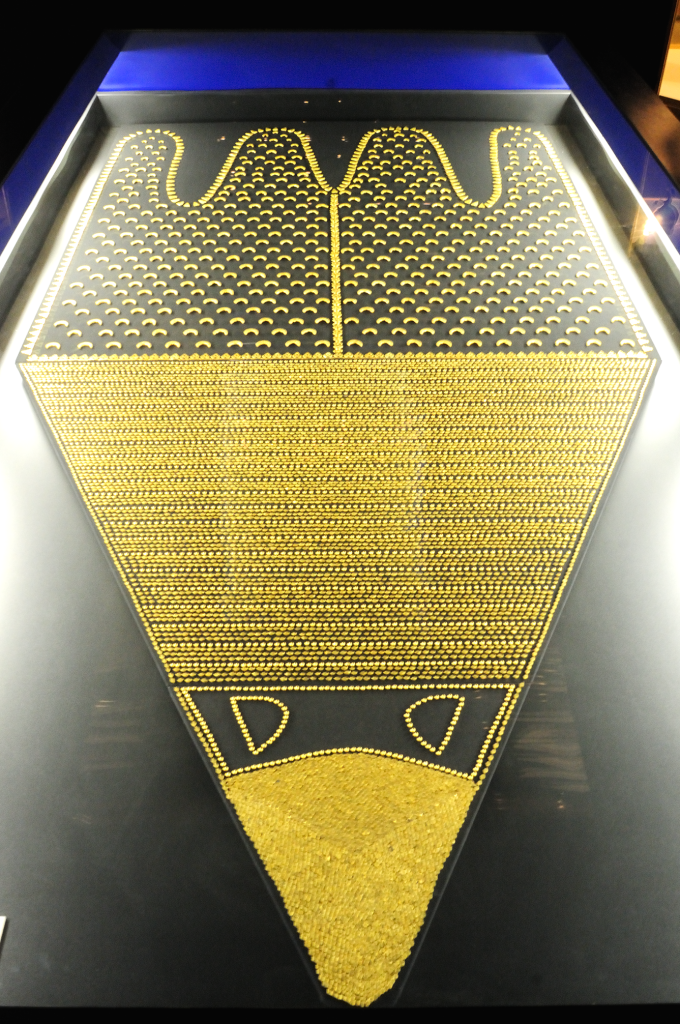

Because of gold’s intrinsic worth it is also easier to transport in the form of small objects of great value: nomads could not have their wealth tied up in permanent fixed structures, such as palaces, or bulky commodities; tribal wealth in the form of gold was easy to transport, usually on one’s person in the form of ornament. In effect the tribal chief was the palace (or at least the state treasury). Their other form of transportable wealth was the hoof, and horses often figured as highly in Scythian burials as gold did.

The nomad’s way of life also involved long periods of leisure, usually in the winter months, and decorative objects are often the result of such leisure. Carved objects of wood and bone are a characteristic of the nomadic lifestyle everywhere and at all times. Such skills would easily be transferred to working gold into the wonderful objects, ornaments and works of art that so characterise Scythian culture. The subjects depicted on these objects were equally a part of their way of life: their myths, the world of the steppe about them and the animals they observed there. This gave rise to their most distinctive style: the ‘animal style’.

Elements of Scythian Art

The Animal Style

Tuva, Kyzyl

The most distinctive feature of the art of the steppe was defined by Michael Rostovtzeff in 1929 as the ‘animal style’.v The term has since been questioned;vi nevertheless it is a recurrent motif and remains in common use, so is a convenient shorthand for the present purposes (so long as one remembers its limitations). Steppe animals, such as deer, are depicted in a very vigorous manner with exaggerated swept-back antlers, often dramatically depicted in mid-movement.

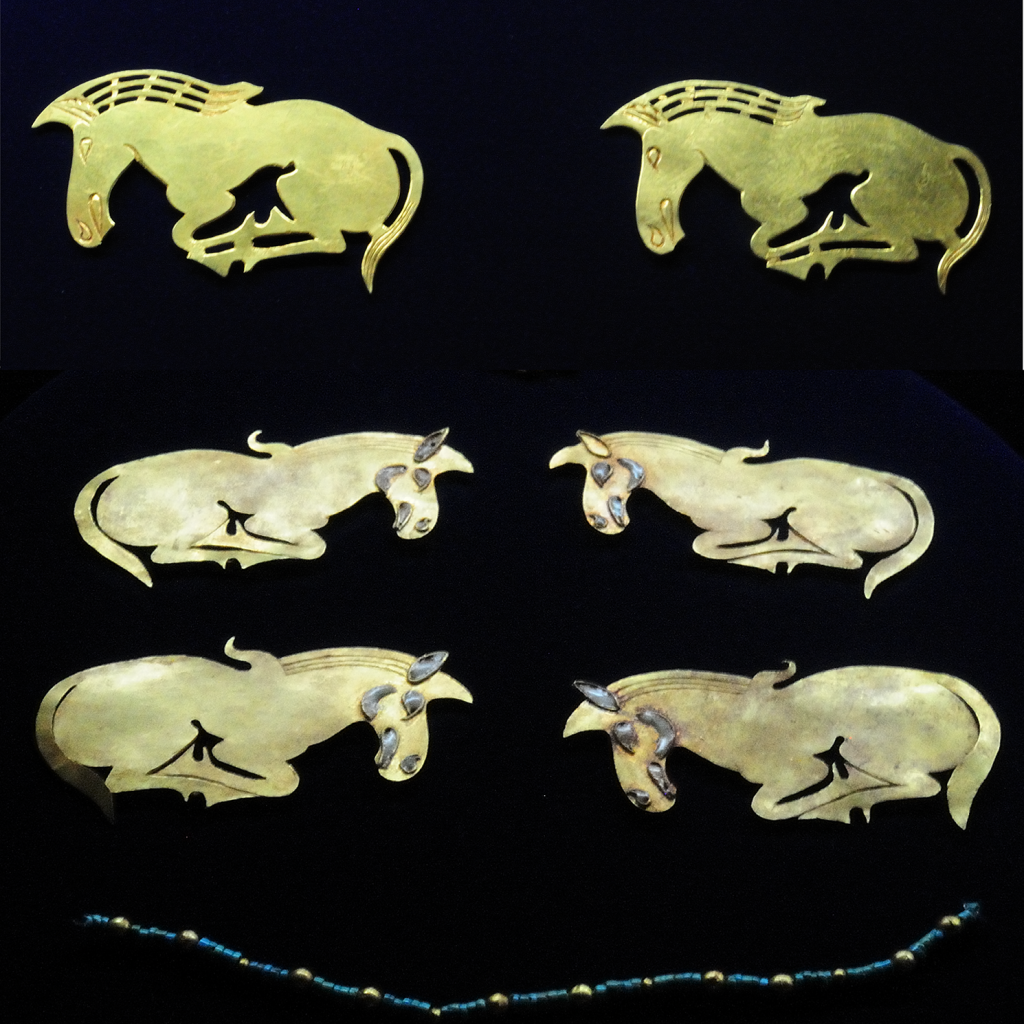

As well as deer and other steppe and forest animals, eagles, boars, leopards and other felines feature, as well as mythical birds and animals such as griffins, often depicted in minute detail. A recurrent motif is one of animals with their backs in a pronounced curve, sometimes even forming a circle. This often gives the impression of the animal in motion, caught, as it were, in full gallop. The motif has also been interpreted as the paws tied together, as if for sacrifice.1 It is certainly one of the most powerful images of Scythian art, and a gold breastplate in the form of a feline curved around to form a complete circle is one of the most powerful objects in the Peter the Great collection in the Hermitage.

Decorated Horses

It is hardly surprising that horses came in for particular attention in steppe art, as horses are a mainstay of the life of the steppe nomad (and horse sacrifices figured hugely in Scythian funerary rites, with over four hundred sacrificed at Arzhan 1, for example, with almost as large numbers in later Scythian burials in the north Caucasus).vii Horse trappings could be highly decorative: plaques, bits, cheek pieces, breastplates and other horse ornaments were ornately wrought or carved and often depicted animals: animal art for animals. A wide variety of materials was used for horse decorations: as well as bronze and gold, decorated leather and wood (also occasionally gilded) were used, as well as patterned felts. Saddles, bridles and reins glittered with gold ornament in some of the horse decorations. A peculiarity of some of the horse burials in the Altai – notably Pazyryk – was false antlers placed on the heads.

One cannot view steppe art in terms of a single style. Although recognisably interconnected, the art was, like the nomads themselves, constantly on the move and evolving. It was always absorbing elements from the cultures and civilisations around – Chinese, Persian, Anatolian and Greek are the main ones – and in turn contributing to them. Above all it must be emphasised that an article of steppe art was designed to be seen but not looked at. A belt buckle or a horse bit was nothing more than a belt buckle or a horse bit: nobody (except perhaps the wearer) would actually look at the individual pieces in the way that modern art historians do. But the whole – the entire decked-out man/woman/corpse/horse/wagon – was very much designed to be looked at, for show – and presumably on special occasions only when even the whole would be but a small part of a greater whole. Then one would no more notice the belt buckle than the cut of the hair, the horse bit than the breed of horse. A person adorned is the person, not the sequin; one admires the classic car, not the hub cap.

Enjoyed this extract? Find out more about Scythian art and much more in The Eurasian Steppe, available to order now from Edinburgh University Press.

About the Author

Warwick Ball is a Near Eastern archaeologist and author who spent over twenty years carrying out excavations, architectural studies and monumental restoration throughout the Middle East and adjacent regions. For five years he was founder, editor and Editor-in-Chief of Afghanistan, the journal of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies published by Edinburgh University Press. Two major academic books, the Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan (Oxford University Press) and The Archaeology of Afghanistan (Edinburgh University Press) were published in 2019.

[1] Or asleep: most animals, especially felines, curl round almost into a complete circle when sleeping.

[i] Jacobsen, Esther, 1995. The Art of the Scythians. The Interpretation of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenistic World, Brill: 1.

[ii] There are numerous books on Scythian art, e.g. Rostovtzeff 1929, Jettmar 1967, Rolle 1989, Jacobsen 1995, Korolkova 2006, Meyer 2013.

[iii] Jacobsen 1995: 1–2.

[iv] Baldick, Julian, 2000. Animal and Shaman. Ancient Religions of Central Asia, I.B. Tauris: 16–17.

[v] Rostovtzeff, Michael, 1929. The Animal Style in South Russia and China. Princeton University Press. Reprinted Rome, 2000.

[vi] So, Jenny F. and Emma C. Bunker, 1995. Traders and Raiders on China’s Northern Frontier. University of Washington Press: 13.

[vii] Petrenko, Vladimir G., 1995. ‘Scythian Culture in the North Caucasus’. In Davis-Kimball et al. (eds): 5-22.