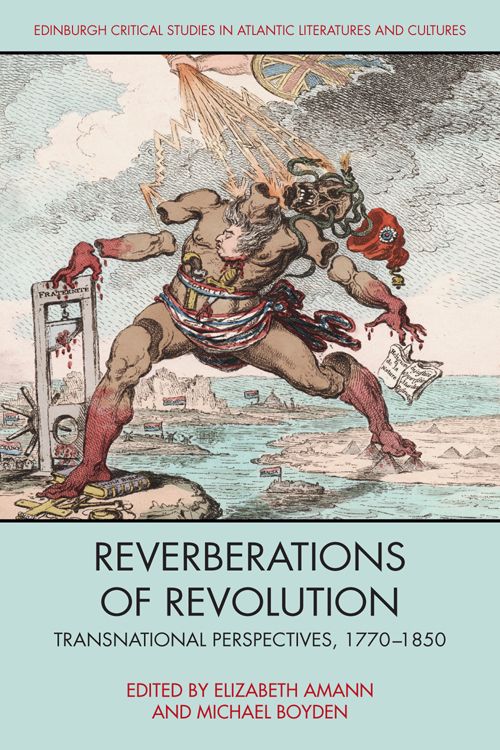

by Elizabeth Amann & Michael Boyden

1. How did this book come about?

Michael: This collected volume came out of a research network on revolutionary cultures involving the universities of Ghent, Göttingen, Groningen, and Uppsala. From the beginning, our aim was to explore how revolutions – which by definition present themselves as unique events – are remembered, repurposed, or appropriated in new contexts. The classical studies on modern revolutions (Palmer, Hobsbawm, Skocpol) tend to focus on what makes revolutions special and unprecedented. We decided to look instead at what makes them iterable: how revolutions are repeated, copied, translated. That was our starting point, and we then organized a series of symposia at each of the four institutions in the network in which we explored various aspects of how revolutions reverberate.

2. What inspired you to research this area?

Elizabeth: A few years ago, I published a book titled Dandyism in the Age of Revolution: The Art of the Cut (University of Chicago Press, 2015) in which I explored representations of male self-fashioning during the French Revolution. The study examines a number of dandy figures that emerged in the 1790s and that were used to make various types of political commentaries. The last two chapters examine similar representations that appear in the Spanish and British press of the period, which react to the political situation in France. These figures —the crops in England and the currutacos in Spain— could be considered reverberations of the Revolution. The collaboration with Michael, who at the time was working on the Revolution of 1848 and its transnational repercussions, was a logical next step.

3. What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Michael: What was most exciting for me was the possibility of working for a sustained period on a shared theme with scholars from various disciplinary backgrounds who otherwise might not interact. This resulted in very inspiring and stimulating discussions. It was just wonderful to tease out all these interconnections between revolutionary movements that are often studied in isolation. As we were working on this project, we also saw connections with what was happening in the world around us. We began drafting our proposal for the network in the wake of the Arab Spring, and our Göttingen symposium coincided with the Brexit vote. The morning after, we were all a bit stunned by the result, which “reverberated” during our panels the rest of the day.

4. Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

Elizabeth: When we began this project, I imagined that most of our case studies would involve literary texts, essays, newspaper articles or artworks. I was very surprised then by Marion Loeffler’s research on the words used to convey the concept of revolution in Welsh. Revolution is such a familiar idea for us that one assumes that it is relatively easy to translate but Marion shows that it was not always so straightforward. Her essay traces how Welsh speakers attempted to find equivalent terms in their language and how the vocabulary evolved in relation to the different types of revolutions they observed. I was also intrigued by Malte Griesse’s account of representations of Pugachev, the revolutionary impostor who pretended to be the late tsar Peter III in the mid-eighteenth century. Not only is the history of this event utterly fascinating but so is the European reception of Pugachev, who could be represented as an enlightened cosmopolitan or as a provincial barbarian. What is also interesting is the way in which the Russian writers later incorporated these foreign visions of Pugachev in their own accounts. The reverberations echo not only abroad but also back at home.

5. What’s next for you?

Michael: The book I am currently completing deals with climate perceptions in Euro-American picturesque travel writings about the Caribbean during the period 1870-1860 and is thus not directly about revolution at all – although it focuses on what is traditionally labelled the Age of Revolutions. Indirectly, I drew a lot of inspiration from conversations with colleagues in the Reverberations network. I discussed the intimate ties between early American writers and French radicalism with, among others, Clifford Siskin, John Mee, and Wil Verhoeven. I feel that much more remains to be done on such mediations and translations, especially when it comes to the influence of radical French thought on authors and thinkers with a Federalist signature. Maybe I will work on this further for my next book project!

Elizabeth: In my current book project, I continue to study revolutions and their reverberations with a focus on fictional representations of the Revolution of 1830. The July Revolution was a movement that spread to various countries in Europe (Belgium, Germany, Poland, etc.) and that was conceived of at the time as a transnational phenomenon. The literature of the period reflects this consciousness of a common project. My corpus includes not only French novels but also German, English and Spanish texts that grapple with the uprisings taking place in other countries. It is my hope that we will maintain our network on Reverberations of Revolution and continue the very productive exchange of ideas that gave rise to this volume.

About the Book

Cutting across disciplines and linguistic borders, Reverberations of Revolution explores the dissemination and transformation of revolutionary ideas in the period between the mid-eighteenth century and the revolutions of 1848.

About the Editors

Elizabeth Amann is Professor in the Department of Literary Studies at Ghent University, Belgium. She is the author of Importing Madame Bovary: The Politics of Adultery (Palgrave, 2006).

Michael Boyden is chair professor of English at Radboud University Nijmegen. He is the author of ‘Introduction to Special Issue: The New Natural History‘, Early American Literature (University of North Carolina Press, 2019) and ‘Salt and Slavery in Crevecoeur‘, Early American Literature, (University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Enjoy this blog? Check out more here.