by Geoffrey Marsh

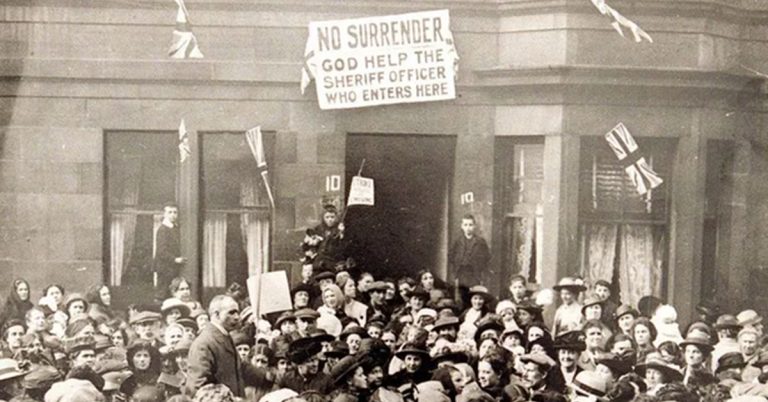

Wednesday 31 December 1600 is one of the pivotal dates in English history. It was not only the end of the 16th century but the day Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to 215 London merchants for what, eventually, became the massive and sprawling East India Company. However, as the project developed in 1599-1600, the original ambition was much simpler; an organisation to challenge the Portuguese naval dominance of the East Indies trade, especially in spices and luxury fabrics, and to ensure that the ambitious Dutch did not steal a commercial advantage over England.

If you walk around St. Helen’s today, you can examine the funerary monuments of three men involved in the foundation of the company. For those who cannot make it to the church, there are pictures of two of these memorials in my Living with Shakespeare.

Given that St. Helen’s was only three hundred yards from the Royal Exchange and the surrounding ‘central business district’ of the Elizabethan City, it is hardly surprising that a significant group of locals from this and adjacent parishes were amongst these first members. From St. Helen’s, the dominant figure was the ex-Lord Mayor (1594/95) Sir John ‘Rich Spencer’, who owned Crosby Hall. His large funerary monument survives in St. Helen’s, although it has been repositioned. He was also an important figure in the Levant Company (the ‘Turkey’ merchants), the organisation chartered in 1592 to trade with the Ottoman Empire. The new company drew members from the Levant Company (20) but even more from previous investors in privateering (27) and the Merchant Adventurers (27).

A second key merchant was Alderman Richard Staper (c. 1540-1608) who lived in the next-door parish of St Martin Outwich, ‘by the well with two buckets’. His fine funerary monument can also still be seen in St. Helen’s, where it was moved to when St. Martin’s was demolished in 1874. It records his crucial role inthe development of England’s international trading, the inscription recording ‘hee was the greatest merchant in histyme the cheifest Actor in Discoveri, of the trades of tvrkey, and East India….’. Staper was one of the twenty-four directors chosen to manage the new company.

In terms of proximity to Shakespeare, the most significant were the members of the Robinson family. Alderman John Robinson the Elder, a potential investor in September 1599, lived in a large house carved out of the north wing of the St. Helen’s nunnery, less than a hundred feet to the north-east of the likely location of Shakespeare’s lodgings. However, he died in February 1600 but three of his sons, Henry, Robert (who took over his father’s house) and Humphrey were members, as was William Walstall (St. Peter, Cornhill), whose daughter married John’s son Arthur and his son-in-law Robert ‘Sandy’ Napier (St. Martin Outwich). His eldest son, John the Younger, with whom he was in dispute in 1600, was not a member but in 1603 he married Susan, the daughter of Alderman Edward Holm(e)den, who was a founder and director. John Suzan, an important trader to Morocco and a witness to Robinson’s will, was recorded as an investor in 1599 but was not in the final 1600 listing.

Two more of the original members, Thomas Marsh and John Hewitt appear to have moved into St. Helen’s after October 1599 but before October 1600 when they are recorded in the Lay Subsidy roll. Humphrey Bass(e) seems to have moved into the parish c. 1605. So, at least half a dozen residents were directly involved in the 1599/1600 founding and a generation later Crosby Hall was the headquarters of the East India Company from 1621-38.

What did Shakespeare make of all the discussions over the previous months leading up to this massive investment in international exploration and trade? The short answer is we do not know. It is unclear whether Shakespeare was living in St. Helen’s after October 1598. By 1602/04 he was definitely living as a lodger in the house of Christopher Mountjoy in Silver Street in the parish of St. Olave, in the north-west corner of the City, close to the modern Museum of London. However, his was probably far more focused on local concerns. Late 1598/1599 saw the Lord Chamberlain’s Men seize the timber frame of the Theatre in Shoreditch and transfer it across the Thames to form the core of the new Globe Theatre. At this point, Shakespeare’s priority was the financial success of this new theatre venture. Furthermore, Bearman’s recent detailed research on Shakespeare’s finances suggests that, following his purchase of the extensive New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1597, his investment strategy was to build up property holdings around the town. Therefore, although Shakespeare set many of his plays in the Mediterranean and created characters from north Africa, ‘O brave new world’ was not to appear until The Tempest written c.1610/11.

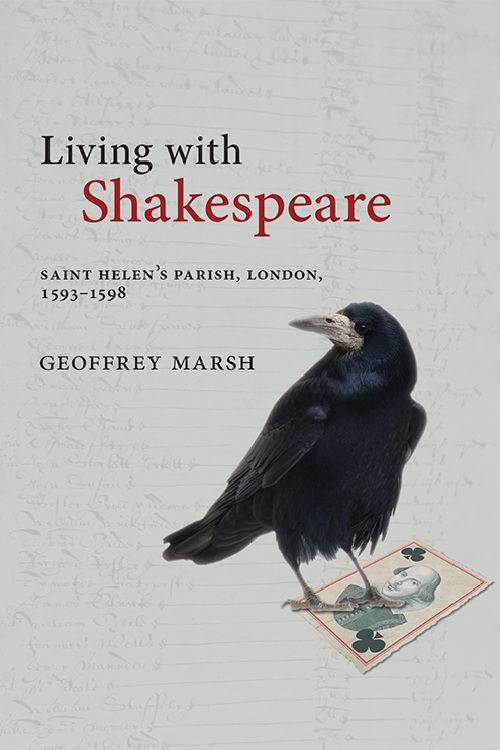

About the Book

Living with Shakespeare examines his parish, church, locale, neighbours and their potential influences on his writing–from the radical ‘Paracelsian’ doctors, musicians and public figures–to the international merchants who lived nearby.

Geoffrey Marsh is runs the Theatre and Performing Arts department of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He is the co-editor of David Bowie Is and You Say You Want a Revolution: Records and Rebels, 1966-70.

Enjoy this blog? Read more from Geoffrey here.