by Jürgen Pieters

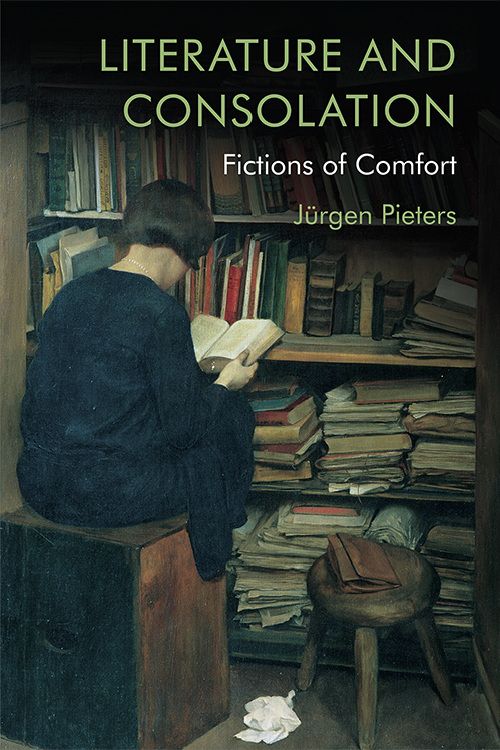

The painting on my new book’s cover was made by the Viennese artist Friedrich Frotzel (1898-1971). Its title – ‘The Old Bookcase’ – makes it even more appropriate. The library of comfort, as I make clear in my book, is a very old bookcase indeed. The period that I traverse in the course of the book’s six chapters – from Homer, through Dante, Shakespeare and Flaubert up till today – is dauntingly large. However, as I mention in the book’s introduction, my goal was not to survey the entire history of the interrelationships between literature and consolation. What I wanted to do, was to show how the idea that readers derive consolation from the books that they turn to in moments of distress – a critical intuition that we hear quite often nowadays – is itself underpinned by ideas and notions derived from a dual conceptual history, that of literature and poetics on the one hand and that of consolation on the other. Representing specific moments in which these two historical trajectories intersect, my selected case studies tell us something about the development of the two concepts considered in isolation.

The woman on the painting, in my predictable reading of Frotzel’s beautiful image, is looking for comfort in the books that she finds assembled in the old bookcase in front of her. She may well have found it in the volume that she is visibly engrossed in. The white handkerchief that is lying on the ground – it must have dropped – is clearly meant to catch our attention. I take it this female reader is not simply having a cold. She must be sad, for whatever reason. Could it be that she is in mourning? The black dress she is wearing is surely not sufficient proof in itself. Also, since the painter has allowed her to turn her back on us, it is impossible to detect in her facial expression further signs of distress.

Still, the book that is sitting in the young woman’s lap clearly renders her handkerchief useless. Whether or not it really alleviates her sadness, we can only guess. But even if she turned around for a moment to look us in the eye, the outcome of her consolatory reading would still be for her to decide. Frotzel’s painting remains silent on the identity of the books and the other writings in this library of comfort. While the spines of a few of the books on the painting seem to be adorned with titles or the names of authors, none of these are legible. The painting is dated 1929. Some Rilke perhaps? Who knows?

Different books have different effects on different types of readers. Some will manage to provide comfort for numerous readers, but leave other readers unresponsively cold. Some books will provide comfort to different readers for different reasons or in different respects. Joseph Luzzi and Rod Dreher, as I show in the second chapter of Literature and Consolation, were both comforted by Dante’s Divine Comedy, but the book clearly did not simply result in a common consolatory experience.

In order to be comforted by books, we need first of all to be responsive to their effects. Once we understand literature’s potential to console better, we might even find comfort in texts that first appear to be anything but comforting. At one particularly interesting moment in his Paris Review-interview, Mark Phillips briefly turns the tables on his interviewer, asking him what he thinks of the Randall Jarrell-line ‘The ways we miss our lives is life’ that Phillips discusses in the ‘Prologue’ to his book Missing Out. ‘I don’t know what it’s about’, the interviewer says, ‘but it strikes me as true, and painful because it’s true.’ ‘What’s painful about it?’, Phillips wonders. ‘It could be extremely comforting, couldn’t it?’ Since the interviewer doesn’t seem convinced right away, Phillips goes on to explain: ‘I’m saying there could be comfort in that line. And the comfort would be something like, You don’t have to worry too much about trying to have the lives you think you’re missing. Don’t be tyrannized by the part of yourself that’s only interested in elsewhere’.

The issue is not so much whether or not Jarrell’s line is or is not consoling. The issue is that in matters of literary consolation it is up to readers to decide whether or not they want to be comforted, even though putting it like this might be overstressing the impact of the will in matters of consolation. Quite often, being comforted is something that happens to us, unexpectedly. This is especially the case when we happen to come across a passage in a literary text that moves us in the way that comfort can. The young woman in Frotzel’s painting may well be on the verge of experiencing such a moment. Whether or not the author she is reading intended to write words of comfort is not really relevant. What matters is that the words on the page, in the full ambiguity that we like our literary texts to display, reach out to this reader and allow her to come to a new insight that makes life more bearable.

The large majority of visual representations of comfort that I know picture two people. One of them, the person in need of comfort, is visibly sad. The other person, the comforter to be, stands or sits nearby, usually within reach. More often than not, the latter is putting an arm around the former, or laying a hand on his or her shoulder. The comfort of reading is much harder to visualize, but Friedrich Frotzel’s painting does the job better than most. If we look at the painting through the lens of the topic that is central to my book, it does not take too much imagination to see that the book in the young woman’s lap is, likewise, holding its sad reader in a consoling embrace.

About the Book

Taking its cue from the rich history of consolatory thinking, the book shows how writers from different times have explored the potential of their writing to offer solace. The result of these explorations, this book argues, has shaped the history of Western literature decisively.

About the Author

Jürgen Pieters teaches Literary Theory at Ghent University, Belgium. He is the author of Moments of Negotiation. The New Historicism of Stephen Greenblatt (Amsterdam University Press, 2001) and Speaking With the Dead: Explorations in Literature and History (Edinburgh University Press, 2005).

While I wholeheartedly agree with the comfort of books, I think that what is depicted is a bookshop employee set to the task of dusting the books, then, being drawn to one of them, stops mid-dusting to read it, dropping the dusting cloth.