By Marek Sroka

Seventy-five years ago, Winston Churchill, in what was to become one of the most famous orations of the Cold War, declared that “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” At that time, which Churchill called “these anxious and baffling times,” few could have predicted that it would take almost half a century to tear down the walls that had divided Europe into two adversary blocs.[1] Meanwhile, the question that many were considering, including George C. Bidwell, the first postwar head (representative) of the British Council in Poland, involved possible cultural cooperation and engagement “with a communist-dominated, and even with a Russian-communist-dominated state.”[2] Although there were some differences of opinion regarding the best approach in presenting British culture in People’s Poland, the Council had never wavered from its commitment to engage culturally with Britain’s ideological adversary, despite (or perhaps because of) Polish government-sponsored occasional anti-Western campaigns aimed at discrediting and intimidating Western institutions operating in Poland. Moreover, British officials were aware of the positive reception of the Council’s work by a large segment of the Polish society. Donald Gainer, the British Ambassador to Poland (1947-1950), warned that “if the Council was either to be closed down in Poland or seriously restrict its activities,” the Polish people would take that “as the final indication that Great Britain had abandoned Poland.”[3]

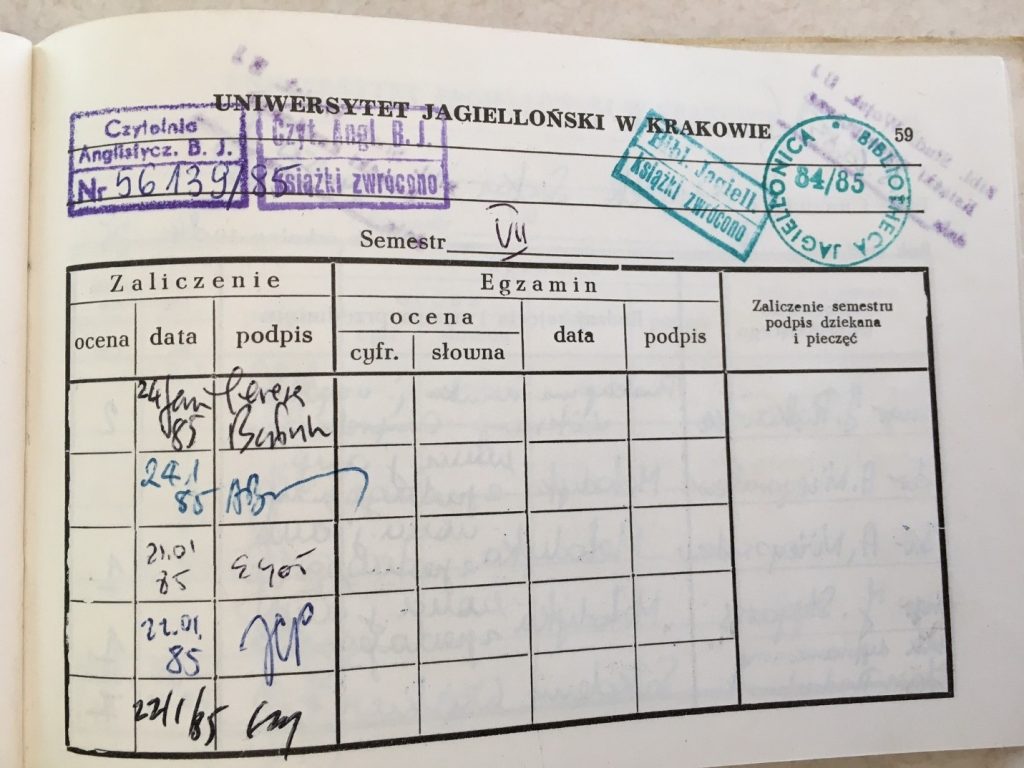

How can we assess the Council’s impact on Poland’s cultural and educational institutions during the Cold War years? In my recent article (‘Spreading the word’ in the Polish People’s Republic: the British Council and the English Reading Room at the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków, 1946–1989) published in Library and Information History, I tried to answer this question by focusing on the Council’s library work, especially its reading room at the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków. The Council’s cooperation with the Jagiellonian University led to the development of remarkable library collections and services and allowed it to expand its library operations into the university setting and reach a significant segment of academic population in southern Poland. I can attest to that as I was one of many students who frequently visited the Council-sponsored English Reading Room at that time.

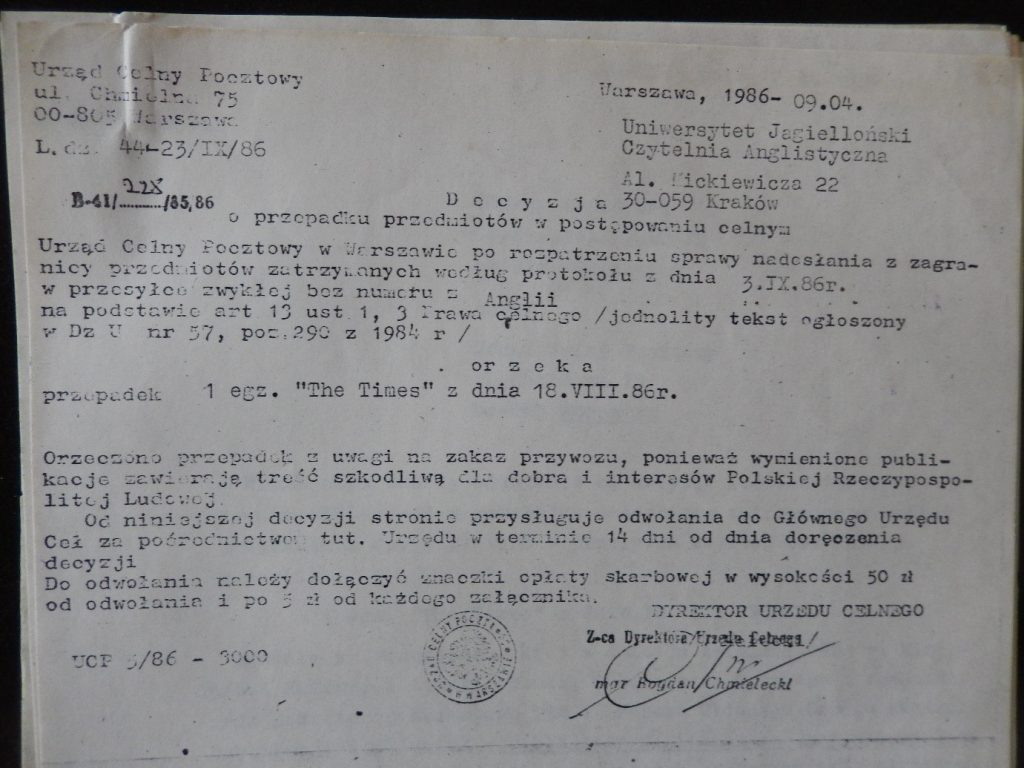

However, what is even more interesting is the Council’s role in providing Polish readers with books that would have been considered “subversive” by the state censorship. The most glaring example were the works by George Orwell, including Animal Farm, 1984, and Homage to Catalonia. The importance of those titles in the collection of the previously mentioned English Reading Room should not be underestimated. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Orwell was the second most translated foreign writer in samizdat editions, after Solzhenitsyn, in Poland’s burgeoning underground publishing market. Thanks to the Council’s library collections, anybody with a decent command of English could read Orwell in the original. Although, there is no evidence of censoring the British Council library collections in Warsaw or in Kraków, I have come across a few cases involving the confiscation of some British journals by the authorities. The confiscations occurred from 1984 to 1987 and included titles subscribed to by the English Reading Room such as Encounter, New Statesman, The Economist, The Observer, The Spectator, The Sunday Times, The Times, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Times Higher Educational Supplement. The Customs and Postal Office in Warsaw, that carried out the confiscations, notified the Jagiellonian Library about the seized materials stating that “the publications include content harmful to the well-being and interests of the Polish People’s Republic,” and thus they were forbidden from being imported to Poland.

We can only assume that the appropriated pieces must have reported on the topics that the authorities would consider objectionable on the grounds of their “anti-Communist” or “defamatory” character. Paradoxically, the University’s objection to the confiscation of British periodicals reaffirmed its right to collecting foreign literature and tested the boundaries of intellectual and academic freedoms. Although, it would be presumptuous to conclude that the Council’s activities had direct impact on the democratization of Poland’s political system, it would be hard to overlook its positive impact on Poland’s cultural evolution towards more open and free society.

Perhaps, those “lessons from the past” can still be useful in our challenging times, including the need for cultural cooperation that has long been seen as a way to further understanding between countries, whether friend or foe.

[1] Winston Churchill, “Iron curtain” speech, 5 March 1946. The National Archives (NA), https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/cold-war-on-file/iron-curtain-speech/ (accessed 5 March 2021).

[2] George C. Bidwell, ‘The Council and Communist Culture’, 1 September 1947, NA, BW 51/14.

[3] The British Council Work in Eastern Europe, 25 May 1948, BW 51/14, NA. The feeling of abandonment (or even betrayal) by the West was quite deep-rooted in Poland after 1945.

Marek Sroka is Andrew S. G. Turyn Professor and Literatures and Languages Librarian at the University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research interests include the history of Polish libraries and the post-World War II cultural reconstruction of libraries.

Library & Information History is the journal of the Chartered Institute of Library & Information Professionals, and the only British periodical devoted exclusively to the history of libraries and librarianship and to the burgeoning field of information history. The journal publishes works about all subjects and all periods related to the history of libraries and librarianship, and to the history of information. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.