by Patricia Pisters

Watching horror movies

Previously, I truly disliked horror films. In the late 1980s Brian de Palma’s Carrie (1976) was shown on television. I did not want to see it, but my friends and sister convinced me that I should stay in the living room and watch with them. It was a nerve-wracking experience. I had no way of distancing myself from this poor girl covered in blood on her prom night, and from her humiliation and the unbridled fury unleashed from within. I did not see the point of the gruesome images, shocking suspense and the dominance of fear and disgust that Noël Carrol identified as the dominant emotions of the horror genre in his seminal book Philosophy of Horror (1990).

Some years later, however, after I had discovered the powers of cinema, studied film at university and worked in a film-oriented bookstore named Cinequanon in Amsterdam, I had a change of heart. In a small corner of the store there was a cult video section. One day a most angelic-looking boy entered, asking me with the kindest shy smile: ‘Excuse me, but do you have I Drink your Blood and Eat your Skin?’ Baffled by the contrast between his timid and friendly looks and the ferociousness of the title he requested, I handed over David Durston’s 1970 cult film.

Re-zoning gender and monstrous femininity

It was there and then that I decided to give the horror genre another try. In the meantime both Carol Clover’s Men, Women and Chainsaws (1992) and Barbara Creed’s The Monstrous-Feminine (1993) had appeared. Since I had also begun to teach, I designed a course on horror film around these feminists’ interpretations of the genre, and took my students to the carnivalesque Night of Terror in the Tuschinski theatre. Beginning to understand that there is much more to the horror genre then just plain violence and disgust, I learned to appreciate the explicit exploration and exploitation of themes that in other genres often remain that ‘what lies beneath,’ our hidden desires and deepest fears, especially in relation to questions of gender.

While the films discussed by Clover and Creed were all male-authored and the audiences at horror festivals was also predominantly masculine, the genre is also about opening-up and rezoning traditional gender boundaries, albeit often at the expense of women, as Clover argued in her analysis of tropes and themes of the slasher and possession films of the 1970s and 1980s. According to Creed’s psychoanalytic reading of the genre, women are not just damsels in distress, victims of the male monsters, as classic horror cinema would have it, but they often inspire fear and have castrating powers.

Women directors and the poetics and politics of blood

Twenty-five years after these seminal feminist readings of the 1990s, the horror genre has made a come-back with art cinema and even Hollywood appeal, as testified by the films of Jordan Peel. However, thinking about the most salient changes in respect to the genre and gender, I am in particular struck by the fact that since the first publication of The Monstrous-Feminine a great number of women directors have begun to adopt and adapt formal and thematic elements from horror cinema.

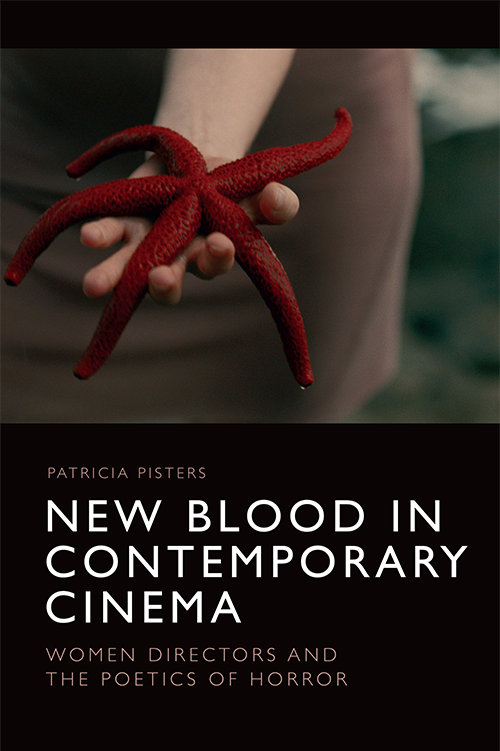

This focus on women directors is the main consideration of New Blood in Contemporary Cinema. Following quite literally a trail of blood and its different shades, hues and values of its red colour in the poetics of the cinema of female filmmakers, I investigate both the formal and affective qualities as well as the particular themes and meanings of horror embedded in these films. Therefore, my initial definition of horror is that there must be blood, ranging from invisible blood of ghosts of the past to just a drop from a nose bleed or a barely-visible scratch to rivers of ruby-red blood covering the entire screen.

While many films in this book contain typical tropes of the horror genre such as monsters, avenging women, vampires, witches and ghosts, there will also be other, sometimes more subdued forms of horror that we will encounter. Taken together, these female-directed horror films demonstrate a fascinating spectrum of the poetics of horror that resonates with the socio-political environment of our contemporary world where Black Lives Matter and #Metoo find expression in the voices of many women that speak out, finding ‘a poetics of their own’.

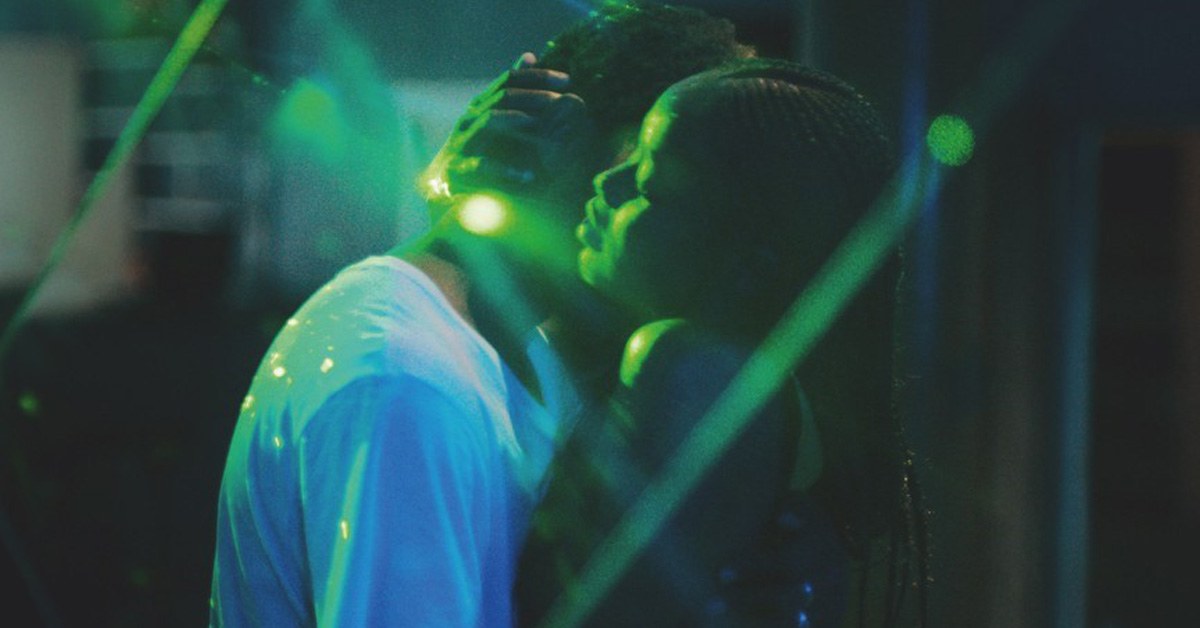

One of the films that I discuss in the book is Mati Diop’s zombie-ghost-love story Atlantics (Senegal, 2019). For the International Film Festival Rotterdam I made a video essay for this film, that raises the ghosts from the sea in an association with other films. You can watch the video essay here. The title of the essay ‘Now the sun had sunk’ is from Virginia Woolf, who also plays an important role in each of the chapters of New Blood in Contemporary Cinema.

Patricia Pisters is professor of film at the Department of Media Studies of the University of Amsterdam. Her latest book New Blood in Contemporary Cinema is available now from Edinburgh University Press. She writes about film, philosophy and media in respect to (collective) consciousness; psychopathologies and psychedelics of contemporary media culture; and on the idea of filmmaker as metallurgist and alchemist of our times. For articles, her blog, audio-visual material and other information see www.patriciapisters.com.