By Richard Rodger

You might think that with a commitment to Open Data and Open Access from the Scottish Government and Local Councils that you would be able to consult Census records from 150 years ago. You might think that having paid your taxes, local and national, that you would be able to consult the electronic version of the Census online.

There’s good news – you can. Go to the UK Data Service and you can download UK Census data for 1861 to 1901 (1911 for England but not Scotland). An excellent guide at Integrated Census Microdata (I-CeM) is also available.

But don’t expect any names and addresses. To obtain these two, ‘safeguarding’ tests have to be passed. One is whether access to names and addresses is prejudicial to ‘personal’ interests. This is rarely invoked for the historical Census. The other is safeguarding the ‘commercial’ interests at stake. In the case of the historical Census, ‘commercial interests’ are cited in order to protect the digital investment made under a contractual agreement between The National Archives (TNA, Kew, London) and DC Thomson Media, to which the National Records of Scotland (NRS) at General Register House, Edinburgh is party. Yes, access to the Scottish Census is dependent on the owner of those other national institutions, The Beano, The Dandy, and the Sunday Post newspaper and its national treasures, The Broons and Oor Wullie.

Making the Census Count: Revealing Edinburgh 1760-1900, my full article in the latest issue of the Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, explores how under present arrangements Scottish historians and the Scottish public are denied access to a publicly-funded historical source, and argues that a ‘pay-as-you go’ approach is inappropriate for access to the Census specifically and archival materials generally. Nowadays, as in the past, we are routinely asked for our ‘name and address’ for almost all transactions and relationships. Linking common data fields is a key tool to enriching historical analysis and to forfeit ‘name’ and ‘address’ also diminishes the productivity of many non-Census sources.

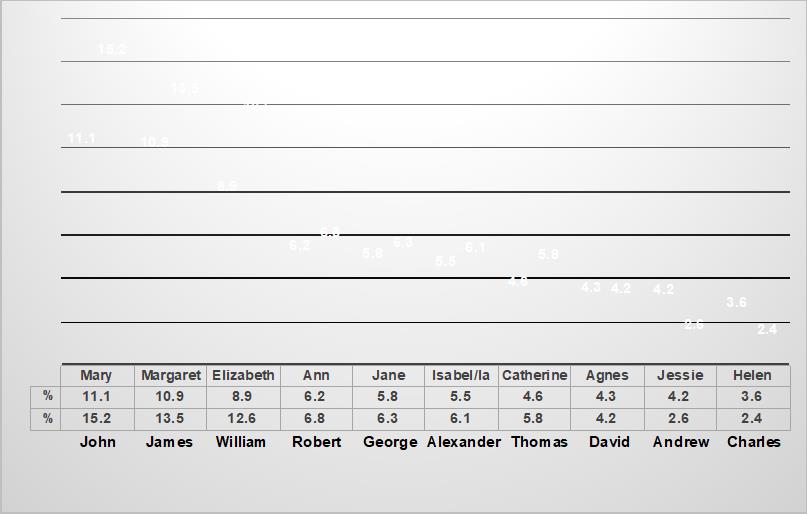

Three examples are used to show how access to access to names and addresses enriches historical understanding. One example for purely illustrative purposes example utilises the Census of Edinburgh to identify the ‘Top 10’ popular male and female names in 1861 (Chart). Another example considers Alfred McNightingale’s addresses over forty years to understand his employment patterns. A third illustration considers a selection of Old Town Closes in 1861 and 1891 in order to reveal how household size and composition was affected by the demolitions initiated under the ‘Improvement’ Act of 1867. None of these strands, and many others, can be undertaken without access to nominal records.

The interests of local historians, genealogist, students and academic historians are adversely affected by current arrangements. The inability to harvest quantities of data from the Census impairs social, economic, cultural, demographic and social science history generally. It limits local interests and civic engagement by denying a legitimate interest in local themes and general trends. School projects and undergraduate dissertations are limited, and for the general public at a time when digital resources are a godsend cannot access their own historical interests. Of greater significance perhaps are questions such as: How can the histories of a nation be written without access to the core data – the inhabitants and their locations? And, when does the contract with DC Thomson end?

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of all is that the terms ‘Archives’ and ‘National Records of Scotland’ did not warrant a single reference in the recently published Scottish Government publication A Culture Strategy for Scotland. That really is shocking. Heritage issues, culture strategies, and planning policies rely on understanding the cumulative layers of the past, that is, the historical record. Our forbears proudly preserved the Declaration of Arbroath, 1320; that is why it can be displayed in its 700th year. Meanwhile the Scottish historical Census is still in lockdown.

The Journal of Scottish Historical Studies is the journal of the Economic & Social History Society of Scotland, publishing the very best research in the rich social, economic and cultural history of Scotland and Scottishness, as well as historical geography, anthropology and historical theory. It is primarily engaged with the ways in which Scottish people of the past lived, worked and played.