By Sarah Nelson

In Scotland and internationally, most policy on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) has placed overwhelming emphasis on children. Traumatised adults have been surprisingly neglected. Yet as I describe in my recent article for Scottish Affairs, the key message from the original ACE studies was the need for changes in the way adults with ill health are heard, diagnosed and treated.

Of these ACEs, attention to childhood sexual abuse (CSA) also remains marginal. For instance, though the current national Scottish training programme to create a trauma- informed workforce is welcome and overdue, almost all specific mention of CSA and its impacts has disappeared. Adults need to be back in the centre-ground of ACEs policy, with a key role for addressing the legacy of sexual abuse.

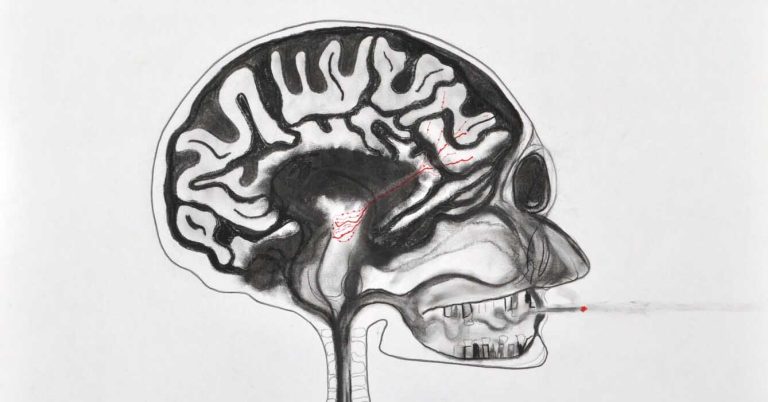

The wide range of damage to mental and physical health which CSA often brings in later life raises an important question. Are some of the ten ACEs widely used as a basis for policy today more influential, more impactful, more dangerous to health and wellbeing over the lifecourse than others? Should they receive greater attention and priority in terms of prevention and recovery? Research and commentary have instead concentrated on the cumulative effects of ACEs, for instance the difference to life experience between ticking three boxes and ticking six.

My paper considers some key questions to ask and answer if Scottish ACEs policy is fully to reflect the experience and needs of adults who suffered the adverse childhood experience of sexual abuse.

These include:

- How far does psychiatric diagnosis now recognise post-traumatic conditions, how far does it remain dominated by biomedical and personality disorder diagnoses? Yet research has revealed the frequency of a CSA history, even in patients diagnosed with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

- How far does the dominance of medication as primary or sole treatment persist, even when a trauma history is recognised? How available are talking therapies, even if Scottish health boards achieve the modest goal of seeing 90 per cent of patients within eighteen weeks?

- How far can survivors of sexual trauma and their third sector support agencies contribute collaboratively to the evidence base of ‘what works’? That is about giving survivors genuine control over decisions about their own treatment and recovery. It is also about moving from offering only certain psychological therapies, towards examining key ingredients of therapeutic approaches which prove most helpful to recovery.

- Since the original and follow-up papers on the effects of ACEs on health are now 15-20 years old, how far are services taking their findings on board today? Do all drug and alcohol services address the extent that substance misuse may be about self- medication of distressing post- traumatic symptoms? Is avoidance of preventive health checks still met with a scolding health promotion approach, rather than sensitive exploration of the reasons?

- How far have health services, including GP practices, dentistry and prison health services adopted survivor-informed guidance about safe, welcoming and trauma-informed healthcare settings? Abuse survivors often fear such settings and decline intimate examinations. That question is also relevant to survivors of domestic abuse, to refugees and asylum seekers, and to victims of sexual exploitation.

Pockets of excellent practice in safe, welcoming and trauma-informed settings need to be copied throughout Scotland. For instance, it is nearly ten years since Health Improvement Scotland in 2011 set out very patient-centred guidelines for work with survivors of sexual abuse during pregnancy, birth and postnatal care. Yet it is unclear if these are currently being followed by midwives and other staff in reproductive health.

In sum, my paper argues that to promote a successful ACEs strategy Scottish policymakers need to show informed thought about how to address – and gradually implement – individual ACEs.

Yet not only has ACEs policy failed to concentrate on the pressing needs of adults. The ACE of childhood sexual abuse itself, which endures “cycles of discovery and suppression” (Olafson et al, 1993) risks disappearing once again from being officially named, or openly addressed.

Reference

Olafson, E., Corwin, D. and Summit, R. (1993). Modern history of child sexual abuse awareness: cycles of discovery and suppression, Child Abuse & Neglect, vol.17(1), 7-24.

Sarah Nelson OBE is a specialist on childhood sexual abuse and its effects throughout the lifecourse, and a research associate of the Centre for Research on Families and Relationships.

Scottish Affairs is Scotland’s longest running journal on contemporary political and social issues and is widely considered the leading forum for debate on Scottish current affairs. Articles provide thorough analysis and debate of Scottish politics, policy and society, and is essential reading for those who are interested in the development of Scotland. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library. You can also sign up for Table of Contents alerts.