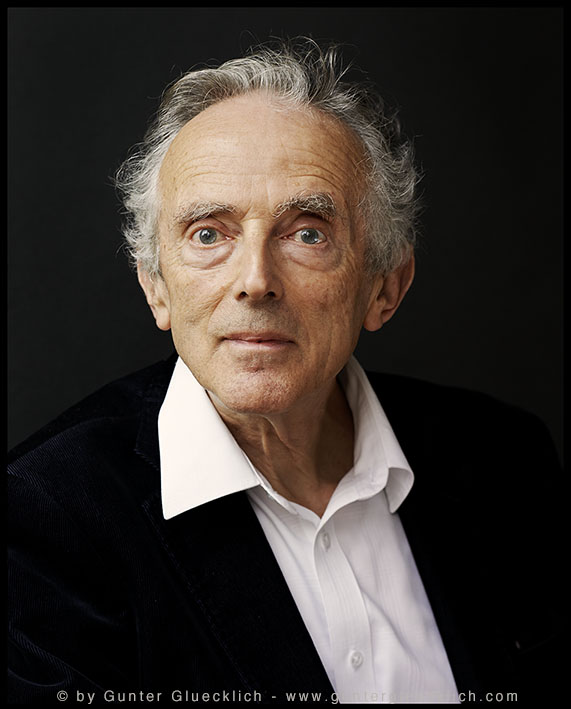

By Peter Burke

The idea that the unintended consequences of human action are often more important – for better and even more often, for worse – than the intended ones is a well-known theme among historians, whether they study politics, the economy or war. One of the aims of ‘The Jesuits and the Globalisation of the Renaissance’ was to suggest that this idea also has its uses in the history of culture (my other aims were to approach the Renaissance from a relatively unfamiliar angle and to illustrate the importance of globalization before the Industrial Revolution).

Missionaries

In the sixteenth century, many Jesuits left Europe for India, China, Japan and the Spanish and Portuguese empires in the Americas. They went as missionaries, hoping to spread the Christian message in these parts of the globe, but their activities there had far-reaching consequences for Asian, American and also for European cultures. Hence the Jesuits may be regarded as ‘cultural missionaries’ facing in two directions. On one side they brought not only Christianity to the world beyond Europe but also many other items of European culture. On the other, the Jesuits helped to make Europeans more aware of other civilizations, providing information about non-European languages, customs, religions and philosophies.

Art and Architecture

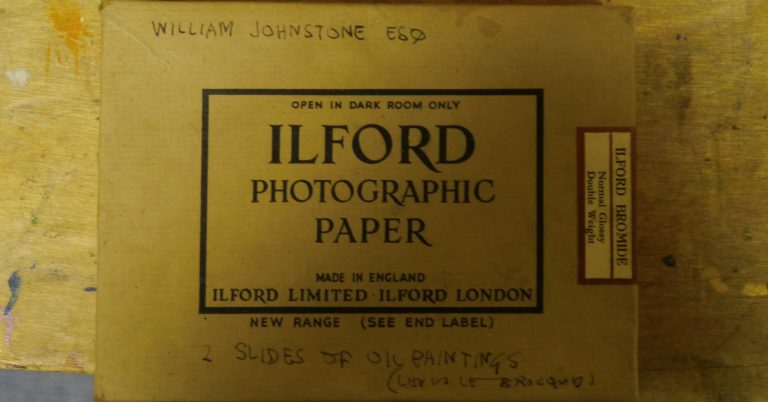

The |Jesuits built churches in what they intended to be the Renaissance style, but their use of local artisans who had been trained in other styles introduced elements of cultural hybridity, as in this church in Arequipa, Peru (fig.1). When the missionaries showed their converts religious images, again in a Renaissance style, they prepared the way, without wanting it or even knowing it, for the later reception of western art outside Europe.

Humanism

A central feature of the Renaissance was the rise of humanism, the study of what we still call the ‘humanities’, especially ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and rhetoric. From Goa to São Paulo, the Jesuits founded colleges that taught these subjects as well as theology. They learned the languages of the peoples among whom they lived and published grammars and vocabularies of Japanese, Tamil, Quechua, Aymara and Tupí, recording some of these languages in writing for the first time. They did this to help a later generation of missionaries but also made an unintended contribution to comparative linguistics. Jesuit descriptions of the customs of the peoples among whom they lived, written once again to inform their successors, circulated in print and helped to widen the horizons of their readers.

Between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, it became possible for Europeans to know more and more about the world beyond their own continent, while others (especially the Chinese and Japanese) discovered ‘the West’. As mediators in this process of cultural globalisation, the Jesuits played a crucial role.

Peter Burke is Emeritus Professor of Cultural History, University of Cambridge. He has written books on the Renaissance and the social history of knowledge and is now working on a social history of ignorance.

Read Peter’s article, ‘The Jesuits and the Globalisation of the Renaissance‘, in the special issue of Cultural History: Global Cultural History.

Cultural History is the only journal in the world that takes cultural history in general as its chief concern, bringing contemporary cultural theories and methodologies to bear on the study of the past, with a broad historical and geographical remit. Its main focus is on the ways in which people in the past orientated themselves as individuals and groups towards others. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.