By Jemma Stewart

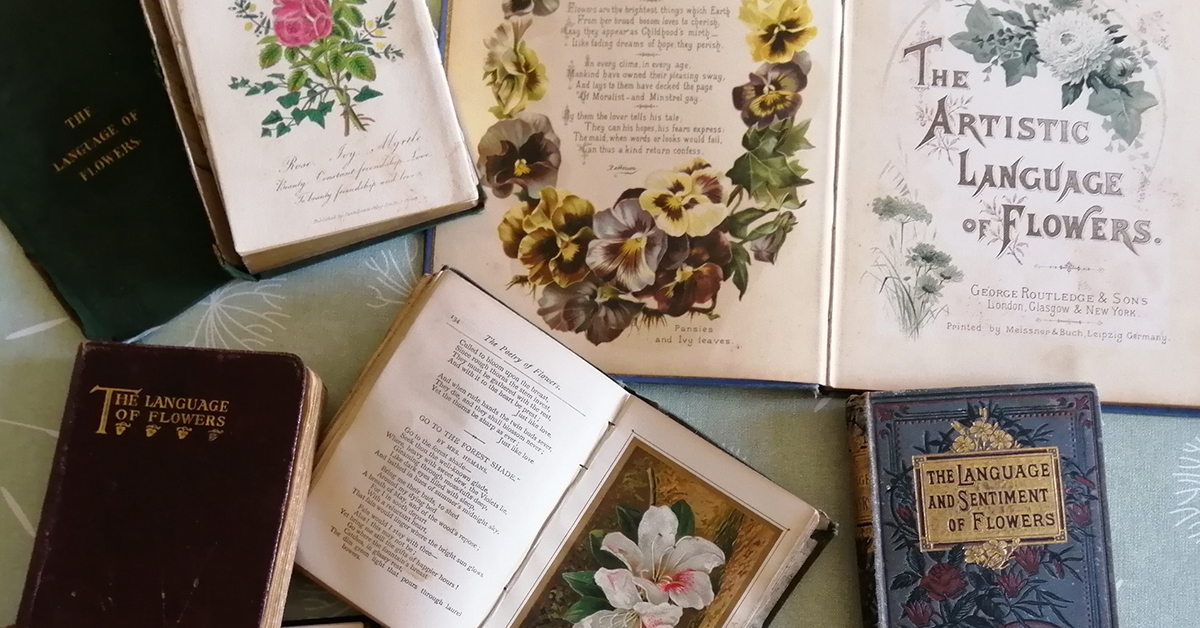

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this blog series.

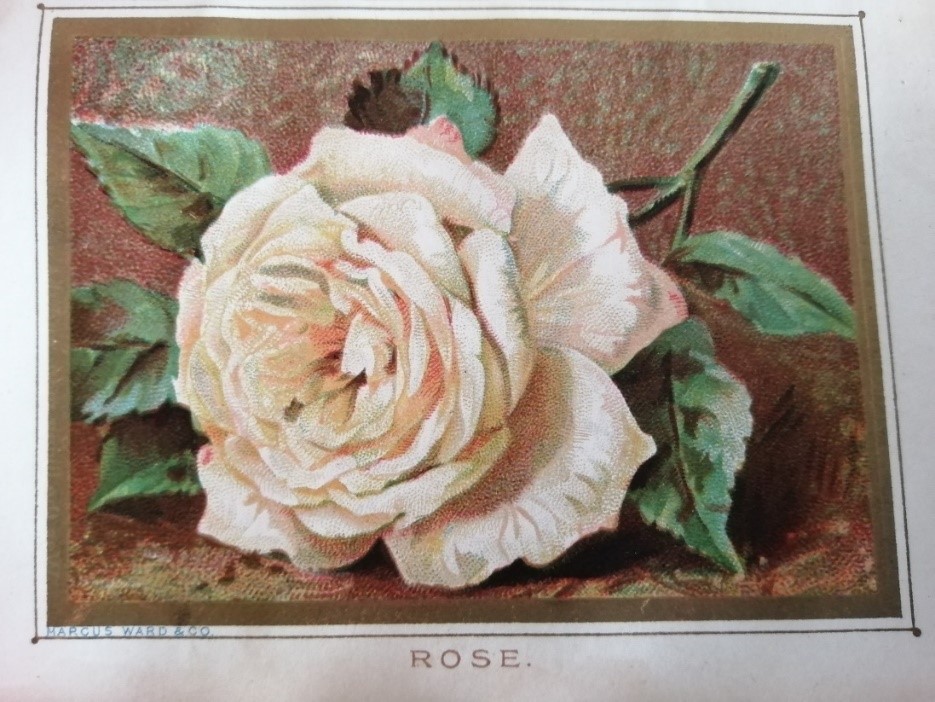

Rose

Roses…have ever reigned as queens of flowers.[i]

The rose bloomed in Ancient Egypt, as Jack Goody attests:

Above all there was the hundred-petalled rose, which became so important a product of Egyptian gardens but was only cultivated under the Ptolemies. All these flowers were used to create the bouquets, chaplets and garlands so much admired by the Romans. Garlands were offered to the army after military triumph. On a domestic level, women placed them in their hair and on their breasts, but men also wore flowers and used perfume, even in war. (43)

Roses in Cleopatra are a symbol of corrupt beauty, venomous passion, extravagance, duplicity and demise. Wearing perfume is not seen as a desirable masculine trait in Haggard’s Victorian reimagining of Cleopatra’s story – perhaps unsurprisingly – see, for example, ‘Perfumes’ in the Graphic (adjacent to a review of Haggard’s Cleopatra, no less) where author A. S. links the dandy and unmanliness to male use of perfume:

Beau Brummel was just the sort of man whom one would expect to find revelling in perfumes, but his craze for self-adornment did not carry him so far, and his protests against the use of them by members of the sterner sex placed an interdict upon this which has never again been overcome.[ii]

In The Language and Sentiment of Flowers, author Laura Valentine states that:

Cleopatra, studying the tastes of the world’s masters, is said to have spent an Egyptian talent, £200, for one night’s adornment of a room with roses, thus excelling in extravagance those fashionable dames who now-a-days pay a florist £50 for an evening’s flowers for their ball-room. (p. 39)

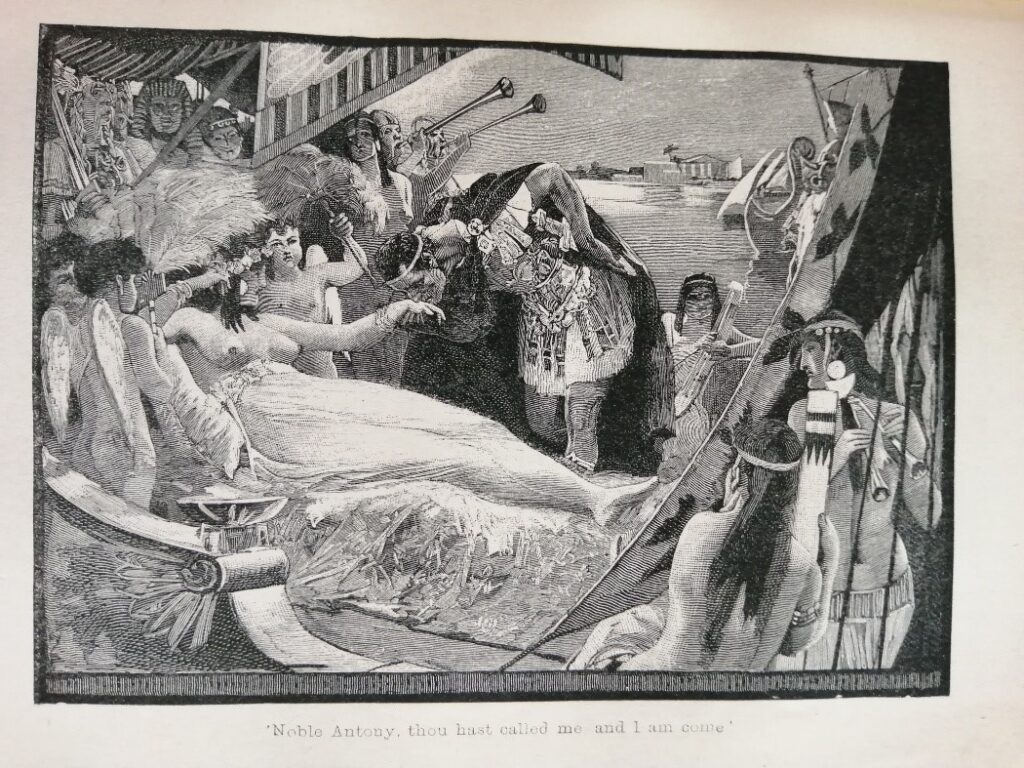

Haggard corroborates this image of luxury and pomp by connecting Cleopatra and the rose, as she decorates with roses ‘strewn ankle-deep, that as the slaves trod them sent up their perfume’ (223). The aura of sensualism cultivated by Cleopatra helps to win Antony over at her feast in the ancient city of Tarsus (223).

Midway through the narrative, Harmachis is adorned with a chaplet of roses by Cleopatra and dubbed ‘King of Love’ (119). This is not appreciated by the recipient:

‘King of Love!’ they crowned me in their mockery; ay, and King of Shame! And I, with the perfumed roses on my brow – I, by descent and ordination the Pharaoh of Egypt – thought of the imperishable halls of Abouthis and of that other crowning which on the morrow should be consummate. (119)

Cleopatra’s treatment of Harmachis and his adornment with roses corresponds with what Mario Praz defines as the romance trope in femme fatale narratives:

Cleopatra, like the praying mantis, kills the male whom she loves. These are elements which were destined to become permanent characteristics of the type of Fatal Woman of whom we are speaking. In accordance with this conception of the Fatal Woman, the lover is usually a youth, and maintains a passive attitude; he is obscure, and inferior either in condition or in physical exuberance to the woman.[iii]

Although Harmachis is supplanted by Antony in the role of youthful lover, and he ultimately kills Cleopatra in Haggard’s version of the story, roses are here displaced onto Harmachis as the male subject to fit this typically feeble ‘lover’ figure for the femme fatale. The displacement causes an inversion of floriographic tropes (the rose more typically emblematising women, their sexuality and ‘bloom’), thus emasculating Harmachis and enslaving him to Cleopatra. As Amy M. King suggests:

The separation of bloom from its female subject denaturalizes the plot’s expectation that blooming signifies the healthy sexual promise of a marriageable girl.[iv]

Roses are used as signs of the frustration experienced by Harmachis – in terms of both his goal to rule and his relationship with Cleopatra. Later in the narrative he attempts, with the help of Charmion, to seek vengeance for the earlier floriographic displacement by poisoning a chaplet of roses intended to be dipped in wine by Antony and Cleopatra to sweeten their beverages (288-91). The plan is thwarted, but the use of roses, here arranged as a deadly trick, embellishes the crowning wreath of Haggard’s poisonous garden. By rejecting the rose as an emblem of love and devotion, Haggard’s roses exemplify voluptuousness, duplicity and tainted love.

Pomegranate

‘Presently something fell out; it was the sceptre of the Pharaoh, fashioned of gold, and at its end was a pomegranate cut from a single emerald’ (187).

Marina Heilmeyer notes that:

Pomegranate blossoms were woven into the necklaces of many high-ranking Egyptians before they were buried. The blossoms were scarlet, but unlike the fruit itself, they had little significance. The ancient Egyptians made a wine from pomegranate seeds, too, that hardly surprisingly, was said to have aphrodisiacal qualities. (p. 30)

Rather than a symbol of fertility or sensuality, the appearance of the pomegranate in Cleopatra is an omen of death – so seductive to Cleopatra that she cannot resist procuring the riches of the tomb erroneously for her own ends. The sceptre of Menkau-ra foreshadows the curse that Cleopatra’s lust for riches and conquest brings down upon her: her desire to maintain power determines the direction of her romantic liaisons with Harmachis and then Antony. The consequence of the curse culminates Cleopatra’s overthrow and demise. This symbol of fertility is therefore reversed in Haggard’s tale, as the only blossoming that occurs is the fulfilment of the curse, albeit, ‘pomegranate’ fruit in the language of flowers often stands for ‘foolishness’ – an apt sentiment in this section of the tale. The connection between pomegranates and death comes to fruition through the reminder of the myth of Proserpine or Persephone, a story revisited by writers and artists in the nineteenth century – see for example Algernon Charles Swinburne’s ‘The Garden of Proserpine’ (1866) or Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s painting ‘Proserpine’ (1874). Haggard’s symbol of the pomegranate has little to do with rebirth, fertility or accounting for the seasons – it represents merely an end for Cleopatra as the cursed treasure, epitomised by the emerald pomegranate, prove too (fatally) tempting.

My current doctoral research investigates floriography within nineteenth-century gothic fictions composed by female authors. I will be looking at whether these women writers conform with, extend or subvert traditional floral meanings found within the Victorian language of flowers. The research will also query the extent to which ecoGothic and ecofeminist analysis can be applied to floriography within the gothic fictions of the Victorian fin de siècle.

[i] John Ingram, The Language of Flowers; or, Flora Symbolica (London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1887), p. 25.

[ii] A. S., ‘Perfumes’, Graphic, 13 July 1889, pp. 45-48 (p. 48).

[iii] Mario Praz, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, in The Romantic Agony, trans. Angus Davidson (London: Collins, 1960), pp.215-321 (p. 231).

[iv] Amy M King, Bloom: The Botanical Vernacular in the English Novel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 207.

Gothic Studies is the journal of the International Gothic Association, and covers the field of Gothic studies from the eighteenth century to the present day, providing an international platform for dialogue and cultural criticism in the sphere of Gothic from within every period and media form. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.