In the final part of this five-part series on African American film, Geetha Ramanathan discusses 2017 hit “Get Out” alongside Kathleen Collins’s “The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy” to consider different ways race relations are portrayed on screen. Click here to read part one of this series.

Hollywood has been a ready conduit of ideas, and in many instances expanded the public imaginary on other cultures and peoples, however imprecisely. In the silent era and later, these included European and Latin American stars. One way in which the Other could be integrated was through the romance story that ceded the Other entrance into the universal narrative of humanity. African Americans however were forbidden from participating in the romance story. Inter-racial romance was labelled taboo by the Motion Picture Production Code or the Hays Code (1930). Narratives of inclusion in the family plot were then arrested resulting in decades of roles as domestic servants, performers, and sidekicks among other diminishing roles. “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” (Stanley Kramer: USA, 1967) with Sidney Poitier and Katherine Hepburn features an inter-racial romance, a romcom, but the joke is on the Poitier character.

African American filmmakers have engaged with other communities in a more egalitarian and comprehensive manner. Two films, one made in 2017 and the other in 1980 pursues the relationship of the minority community to the majority, reflecting on the political, social, and personal dimensions of these relationships.

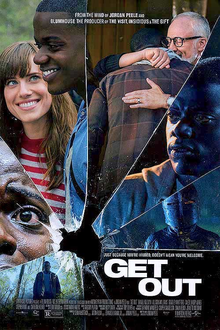

“Get Out” Jordan Peele, USA Blumhouse Production, 2017.

Peele’s hugely popular film gives the romance motif a kick in the teeth when we find that that the romance between Chris, a Black photographer, and Rose, a liberal white woman is part of a larger twisted white supremacist plot. Sci-fi elements blend supremely with the social awkwardness of a first visit to the girlfriend’s parents’ home. The zombie motif is interlaced in this romcom turned horror film. Peele uses this generic blend to question the liberalism of the so-called progressive white community.

The chilling contradiction between the liberal philosophy of Rose’s father—“he would have voted for Obama three times if he could”—as proof of non-racism is laced with an irony that lingers. Its lie is revealed when the couple arrive at Rose’s house. The long shot, showing the parental home, is a reprise of the opening long shot of the plantation genre of films set in the ante-bellum south, complete with the gracious paternalistic father, and the concerned overbearing mother. Their whiteness, evoking the 1950s, contrasts with the zombie-like Black groundskeeper, and marionette-like Black housekeeper. Uncanny for Chris and the viewer, perfectly wonderful —peaches and cream—for Rose and her parents.

Peele’s critique of the depth of entitlement, and enjoyment thereof, experienced by white liberals is bruising and dismissive of liberalism’s capacity to be inclusive, and stresses, rather, its exploitation of Black talent. That the film has given rise to a huge volume of discussion on race relations, specifically the memory of slavery in the US, speaks to the urgent issues of the now.

“The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy” Kathleen Collins USA CGR Productions, Eleanor Charles and various non-profit agencies, 1980.

Four decades ago, Kathleen Collins made a film based on a short story collection by Henry Roth that was a homage to Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” Three Puerto Rican boys, brothers, thrilled to be out of New York City, seek to eke out a living by hot-wiring cars, and doing whatever jobs they can get. The voice of their dead father exhorts them to be virtuous, he having ended up dead after a bungled bank job. He appears only to Victor, the oldest, who is a self-made ethnographer and records the community’s activities and observations. Like Chris in “Get Out” these auteurial surrogates are crucial to lending Black/Puerto Rican subjects an authority over the world and their ability to represent it.

The sequences that show us the exploits of the daredevil brothers —risking their lives running across the side ropes of a bridge—accompanied by an upbeat soundtrack are replete with a joyousness that appeals to all our senses. Another ghost-like figure, but all too real, an old New York lady tails them, marveling at their dance with death. She accosts them and offers them a princely wage to restore her crumbling home to its former glory. As the boys try to accommodate themselves to this somewhat unusual situation, their ease with Miss Malloy is disturbed by the middle brother, Felix’s suspicions, and the youngest, José’s, flirtation with her.

The “marvelous real,” rich with the possibilities of human interchange, animate this film that is shot using the palette of a Romantic artist. Its measured pace urges us to bring colour, sound, and shape together to enjoy this simple story of human contact that avails of the literary, pictorial, and aural.

The film’s plot, based on the unlikely bond between three young Puerto Rican men and an old white woman, speaks to Collins’s philosophical advocacy of trying to listen to the stories of others, and to catch the universal connection as human beings, no less, no more.

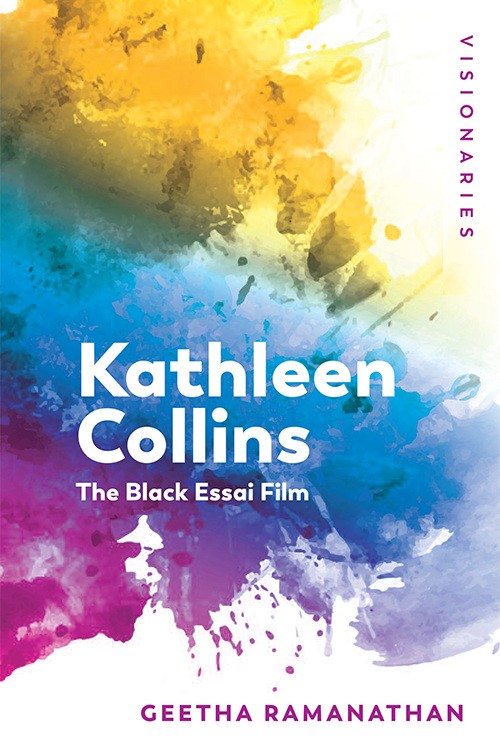

About the Author

Geetha Ramanathan is the author of Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020). She is Professor of Comparative Literature at West Chester University where she teaches Comparative Literature, film and Women’s Studies (including Feminist Film and African American Film). Her interests include modernist, feminist and third world literature.