In part three of this five-part series, Geetha Ramanathan explores the use of American mythology and folklore in two African American films. Click here to read part one of the series.

The great mythology of the US is written on the cinema screen, rendering it imperative for African American filmmakers to find, wrestle with, and imprint their own myths.[1] Too often, critics and cinema-goers look for explicit protest in black cinema and art. Charles Burnett speaks of spending days and hours in the 1970s in UCLA film school trying to define “black film.” In 2017, responding to Robert Townsend’s question of what black film is today, Burnett laughs and shrugs the question away.

And yet, film critics are still trying to grapple with the question. Among others, the films of Kathleen Collins, Charles Burnett, Eloyce and James Gist, and Spencer Williams translate realisms —folkloric, allegorical, magical realist—to create a mythology relevant to their history. When these filmmakers address other African Americans, they come together as a community, remembering their stories even as they question them. As early as the silent cinema era there are examples of African American films that use folkloric beliefs, and religious ideas, culled from the south as a moral basis with which to confront urban modernity.

“Hellbound Train” Eloyce Gist and James Gist. USA: Eloyce Gist and James Gist, 1930.

The film sets out moral choices for the newly migrated African American in strong terms. The modern is presented as unequivocally corrupt in this film that is akin to a Stationen Drama, a play that takes the protagonists through the various stations of their life, the title being a dead giveaway as to the destination. The wider availability of the work of the Gists has been very welcome, and allowed for a larger audience to recognize that there had been African American women filmmakers before the 1990s and the theatrical release of Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust.”

The film is rich in religious imagery and boasts a totally enjoyable Devil figure, almost straight out of medieval plays where the Devil was mocked in the form of the figure Vice. And herein lies the rub with the straight-shooting message about the terror of modernity; the devil is less scary than amusing, pointing to the chiasmus between the narrative weight and the image.

The venue for the exhibition of the films is relevant – the church. It is a surprisingly modern moment in all, given what Baldwin recounts about the unlawful and sinful status film held for churchgoing folk in the 1980s. [2] Clearly didactic in purpose, the film was obviously intended also to be entertaining while presenting a moral. In using such a modern medium to translate the virtues of what was essentially a morality play, the Gists were attempting to persuade the congregation of the dangers of alcohol, and fast city life in general.

Each stage is marked by a shot of the train moving across the screen, and each of the coaches that the passengers climb is classified according to a scheme, not unlike Dante’s. Coach No. 7, for instance, is for liars. The train ends in blazing flames, surely intended for those congregants who can sympathise with many of the misdeeds that are catalogued. The film’s modern form triumphs over the traditional narrative; the other woman’s life comes across as more exciting than the virtuous woman’s. Indeed, if the black female viewer were to identify with the virtuous woman, the pleasure would be masochistic.

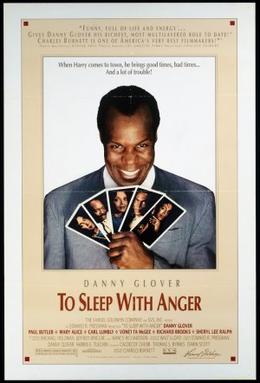

“To Sleep With Anger” Charles Burnett USA: Thomas S. Byrnes, 1990

The opening sequence of the film visually explains what is at stake for the audience, the soul of the human being. A frontal shot reveals fruit on fire, we see several medium shots of a man formally dressed in a white suit, conjuring up images of a funeral. A pan from his face to his shoes reveals that the shoes are in flames, the flames lick upwards. We cut to the same man sleeping under a tree. Ostensibly a dream sequence, the film builds on such imagery to add a level of density to the plot, showing the uneasy existence of conjure and southern rural religious beliefs with urban modernity and assimilation.

Gideon’s family recreates a rural space in their suburban backyard, and live by those values of hard back-breaking work. These values are challenged by his younger son, Babe Brother who swears that he doesn’t want any of this for his son. The entrance of the trickster figure in the form of Harry, an old friend from the South, exacerbates the situation.

Burnett builds tension in the film through a variety of auguries—an egg falling to the floor, a tea-cup breaking, a broom touching a man’s shoe—to create a world that exists in the empirical real of African American life in LA. Danny Glover, as Harry, chills the viewer to the bone. Coming in as the intruder, he quickly seems to have the family under his grip, as he very subtly casts doubt on their ideas.

The vernacular blues aesthetic of the film renders it a pleasure to watch, and connects it to other films in the independent canon that draw the folkloric, and the musical into the visual. One haunting sequence, featuring the trickster and the migrant, recalls African Americans laying down the train-tracks, a reminder of who they were then and who they are now.

[1] Kathleen Collins in a talk at Howard University in Washington DC.

[2] James Baldwin, The Devil Finds Work (New York: Bantam, 1976)

About the Author

Geetha Ramanathan is the author of Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020). She is Professor of Comparative Literature at West Chester University where she teaches Comparative Literature, film and Women’s Studies (including Feminist Film and African American Film). Her interests include modernist, feminist and third world literature.