By David H. Fleming and William Brown

We began writing this weird book (The Squid Cinema from Hell) together at some point in 2016. Its conception or gestation predated this by a few months. We likely began sharing thoughts on cephalopods and cinema during a visiting scholar trip that allowed Will to travel out to China in December 2015 and stay at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, where David was then working. We had written together prior to this on digital cinema, and collaborated on a few other projects.

During this visit to China we presented on a panel entitled ‘The Star, the Squid, and the Posthuman: Three critical, theoretical and philosophical approaches to ScarJo and digital era actors.’ This was a fun panel to do, not only because it was delivered to a packed venue, but because the three papers hung together so well. As if they were planned that way.

The first paper was delivered by Professor Adam Knee, who charted a course through several star studies paradigms to best approach the celebrity phenomenon that was Scarlett Johansson. David then delivered a paper that put Vilém Flusser’s defamiliarising biophilosophical concepts (from his inspirational Vampyroteuthis Infernalis) into dialogue with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s immanent models to describe a clutch of ScarJo sci fi roles and performances. And William’s paper then offered a posthuman engagement on similar films that took a different detour through Deleuze and Guattari and critical race theory. The three papers overlapped like Dutch tiles, and offered a neat cubist approach to the study of this epochal, digital-era star.

At this point we had both just finished writing monographs about the ‘outside’ of cinema, or that which falls outside of the cinematic society (see Brown’s Non-Cinema and Fleming’s Unbecoming Cinema, respectively), and we were planning to write a book together on mud in cinema. We discussed this intensely during the December trip. However, over the following months we most commonly found ourselves sharing ongoing parallel encounters with squids and octopuses (on screens or paper). Peter Godfrey-Smith’s 2016 book Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origin of Consciousness was one we both enjoyed immensely. As was Donna J. Haraway’s Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene,which confirmed we were on the right trail. We started to think that this project really had legs (eight of them!), and that it was somehow part of a larger evental happening.

When we both attended the Film-Philosophy conference in Edinburgh 2016, we decided that we would write a short book together on cephalopods and cinema—as a warm up for the mud book. Octopuses often disguise themselves as mud using their skin-screens, we noted, in order to avoid detection. So, over the next year we collated a huge database of images and readings and films, which gradually made clear that this book was going to be a far bigger monster than we initially anticipated. And by the time we attended the Film-Philosophy conference in Lancaster in 2017 we were known to many as ‘the octopus guys,’ and were getting useful tips and pointers from multiple friends and colleagues. We were also starting to get invites to attend and perform our work (in progress) in various locations.

We were very keen on experimenting with our writing as part of our drive towards a new, soft theory, and a ‘molluskian methodology’ that we were developing as we moved around and in-between various different global locations. One standout event we attended together took place on the breathtaking island of Ischia, which was fittingly close to the place where the zoologist John Zachary “J.Z.” Young had been commissioned to experiment with the octopus brain as a kind of cybernetic template or model for the computing machines that were newly emerging after WWII. By this time our work together was also bearing witness to a novel, eight-limbed ‘third author’ persona that was more than the sum of its parts, and which allowed inky passages to emerge for which neither of us is individually responsible.

It’s fair to say that The Squid Cinema from Hell covers a lot of material and technologies between its eight chapters, conducting as it does a weird media archaeology of global films, music videos, hentai pornography, sculpture, machines, technologies, and multiple other art and image forms. We feel like we trawled and dredged up a lot. But of course, no book can ever cover everything its authors want it to. And there remain so many things we simply had to cut, withdraw, or jettison to come in on size and on time. We have also inevitably discovered many other artefacts and arguments since, which we shamefully remained ignorant of at the time. And there are yet others still that we wish we could have incorporated.

One of the wordplays that we make in The Squid Cinema from Hell is the idea that the universe is a single worm, from the French ver, meaning worm—a link between verse and worms that poets like Charles Baudelaire have made long before us. If the universe thus is a single, invertebrate worm, with its eight legs, the octopus constitutes a multi-verse. And so, in what remains of this blog post, we hope to foreground eight (of course!) other ver-sions of our introduction, which although marginally or not even included in the book itself, are, we feel, clearly linked to the broader evental project, and which thus can help us to introduce the book and the wider project here.

1. The Arrival of an Octopus at the (Train) Station

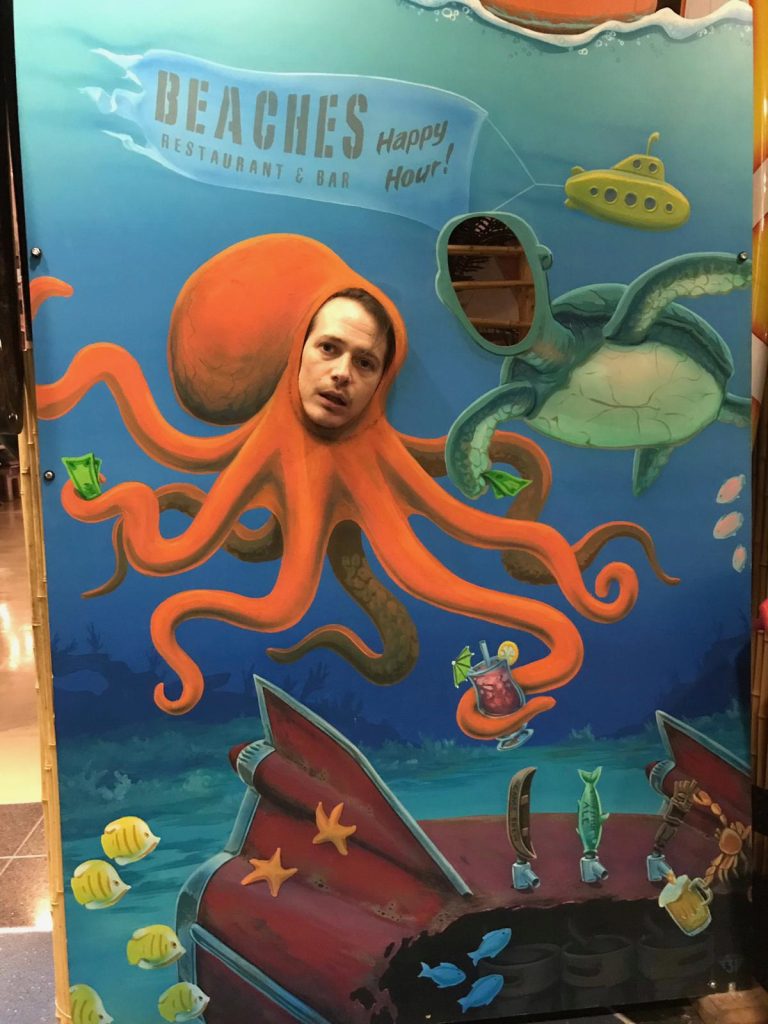

Ahead of a trip to Paris to sit in the cinema and watch the sorts of films that rarely if at all get a theatrical screening in London, William noticed in the summer of 2018 that a giant octopus was situated on a machine about the size and shape of a passport photo booth in the London Eurostar terminal.

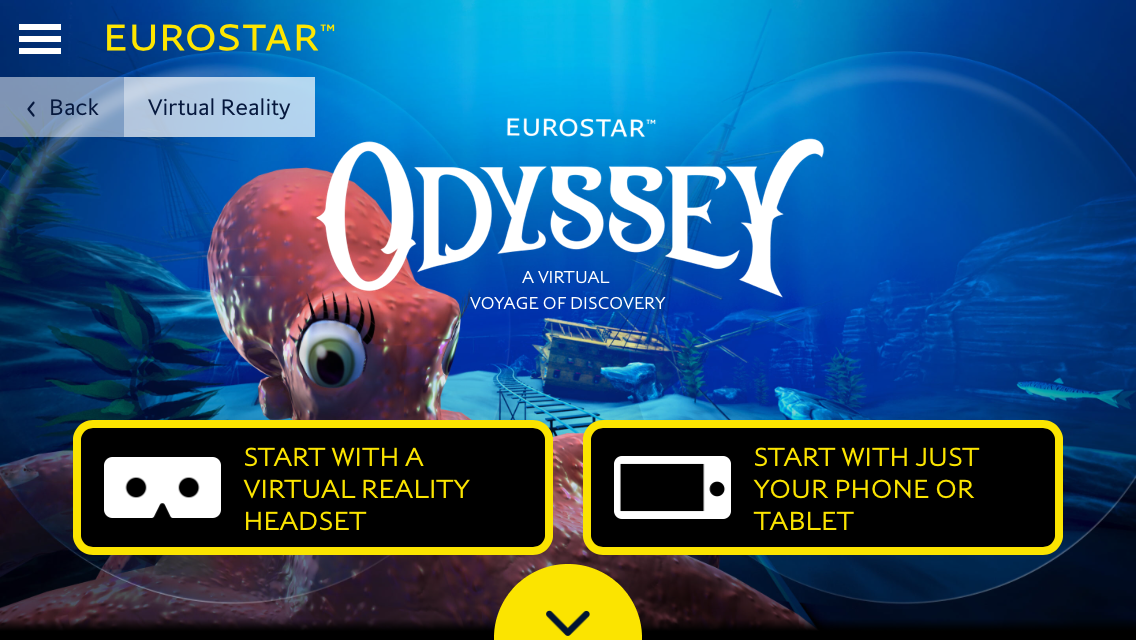

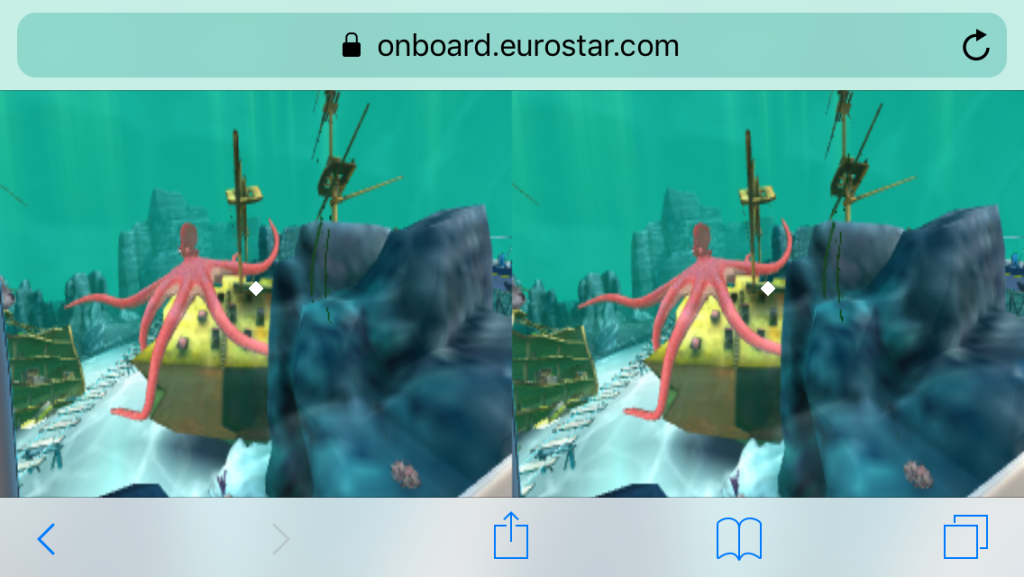

Curious, William shelled out for what was essentially a set of cardboard glasses, but into which one could insert one’s smartphone so as to turn it into a viewing screen for a VR experience entitled Eurostar Odyssey: A Virtual Voyage of Discovery (see image 1.1).

While somewhat uneventful as a VR experience, one can nonetheless sit in the Eurotunnel and look out of the train as if at the surrounding Manche (Channel) within which the Eurostar is enfolded. Included among the beasts that one encounters are of course octopuses (image 1.2).

Although we mention this VR experience in a footnote in The Squid Cinema from Hell, we do not have the opportunity really to investigate its meanings and/or resonances. That said, we might connect this train-based VR experience to another text that we also mention in passing in our book, namely Frank Norris’ The Octopus: A Story of California (1901).

For, one of the definitions of the titular octopus in Norris’ novel is the railway network that is appearing across the USA in the early twentieth century (largely constructed by imported Asian ‘coolie’ laborers, which the novel does not really acknowledge). That is, the tentacles of the railway network are akin to the arms of the octopus, meaning that trains and octopuses have a longstanding figurative, if not literal, relationship.

And, of course, trains also have a longstanding relationship with cinema, thanks to the Lumière brothers’ early Arrival of the Train (1896).

The postcinematic VR experience on the Eurostar, then, completes the con-ver-gent relationship between octopuses, trains and digital media, which, as pointed out above, also have cephalopodic origins thanks to the research on octopus brains by J.Z. Young, which played an important role in the development of digital computing.

Of course, the concept of ‘arrival’ has also now been linked to tentacular culture thanks to Denis Villeneuve’s film of the same name, and which features various cephalopodic heptapods trying to engage humans in timeless con-ver-sation.

In other words, we can chart a course from the arrival of the train, to the arrival of cinema, to the arrival of the digital computer, to the arrival of virtual reality, and to perhaps the arrival of tentacular, alien intelligences…

As arrival means to reach the shore (from the French à rive), so does arrival thus imply the coming to the land of something from the deep. Perhaps this process of arrival is always, therefore, linked to the Emergence of Chthulumedia themselves…

2. A cephalopodic agencement of software, projection, and architecture in Collioure

Continuing the French connection, the charming southern village of Collioure, where the Pyrenees crash into the Mediterranean, is an important geographic location for us both. For one, it is the home town of David’s in-laws. Consequently, beyond being an annual family holiday destination, it is also the place where he got married in 2014. William attended this event, and has since returned to use the beautiful location as the setting of a forthcoming film, Mantis, made through his no-budget production company, Beg Steal Borrow. Saying all this, we mention Collioure here today because the village also boasts a beautiful coastal bay that has, since 2014, witnessed the annual return of a peculiar species of chthulumedia that we barely cover in The Squid Cinema from Hell.

Worth stating here is that the unusual quality of light that floods Collioure and the surrounding picturesque landscape has made it an irresistible historical draw for innumerable artists over the years, including luminaries such as André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Charles Rennie Macintosh to name but three. Nowadays this ‘ville des artistes’ is also a summer touristic destination, a fact that perhaps accounts for the more recent appearance of an annual pop-up son et lumière art event in the winter too, now known as Collioure Couleurs.

Collioure Couleurs sees the town’s iconic round-towered church—which juts out over the harbor waters—become a ‘living canvas’ for a unique projection mapping show. Therein, the latest digital illumination techniques—sometimes known as spatial augmented reality displays—see powerful projectors used to ‘mask’ the church and bell-tower so that they appear to be, for around 20 minutes at least, a moving canvas brought to life by a software-enabled ‘kino brush’ (to use Lev Manovich’s term, see image 2.1).

In one annual show David attended shortly after his wedding, he saw Matisse’s painting of the Collioure church become projected over the building’s actual façade, so that the real setting appeared to withdraw behind an illuminated dermal representation of itself. Many other moving and colourful displays in the style of Matisse have gained new animated (after)life upon the stonewall screen.

To us, such digital expressions and display phenomena surface as computational approximations of what in the book we call, again with brushstrokes of Manovich, cephalopodic “painting in time.” To briefly contextualise in relation to the cephalopod, several writers including Flusser describe the expressive chromatophoric skin-displays of squids, octopuses and cuttlefish as living acts of “epidermal painting”—an idea repeated by Godfrey-Smith who was moved to name one particularly dynamic cuttlefish ‘Matisse’ on account of this animal’s breathtakingly expressive dermal displays.

In The Squid Cinema from Hell we argue that there are material and molecular links between the bio-aesthetic skin-screen displays of soft animals like squids, cuttlefish and octopuses (like those found in the Mediterranean and regularly spotted in the bay of Collioure) and the pixelated renderings of today’s digital (software) machines and screens. To use the language of an eight-limbed French author on this outing (i.e. Deleuze and Guattari), we maintain that an immanent “block of becoming” has been established between the subaquatic invertebrate kingdom and these modern, supersaturated digital machines.

To us, then, the Collioure Couleurs projection mapping displays are an annual reminder that we are indeed living through a ‘chthulumedia’ moment. In the 2015 show, for example, the image of an octopus (and other mythical monsters) projected on to the church façade (image 2.1) served as a fitting prelude to a mobile underwater scene wherein human viewers were transported through an animated volume of water at seabed level to see a variety of other underwater inhabitants. A few years later, in an apparent act of cephalopodic mise-en-abyme, David saw a spatially augmented shoal of bioluminescent cephalopods soar across the building’s 2017 projected skin-screen (image 2.2). In this memorable underwater scene, another mythical sea monster (like a Stoor Worm) then spiralled around a drowning sailor (to see the sequence, watch from 8m50s to 9m15s of the YouTube video:

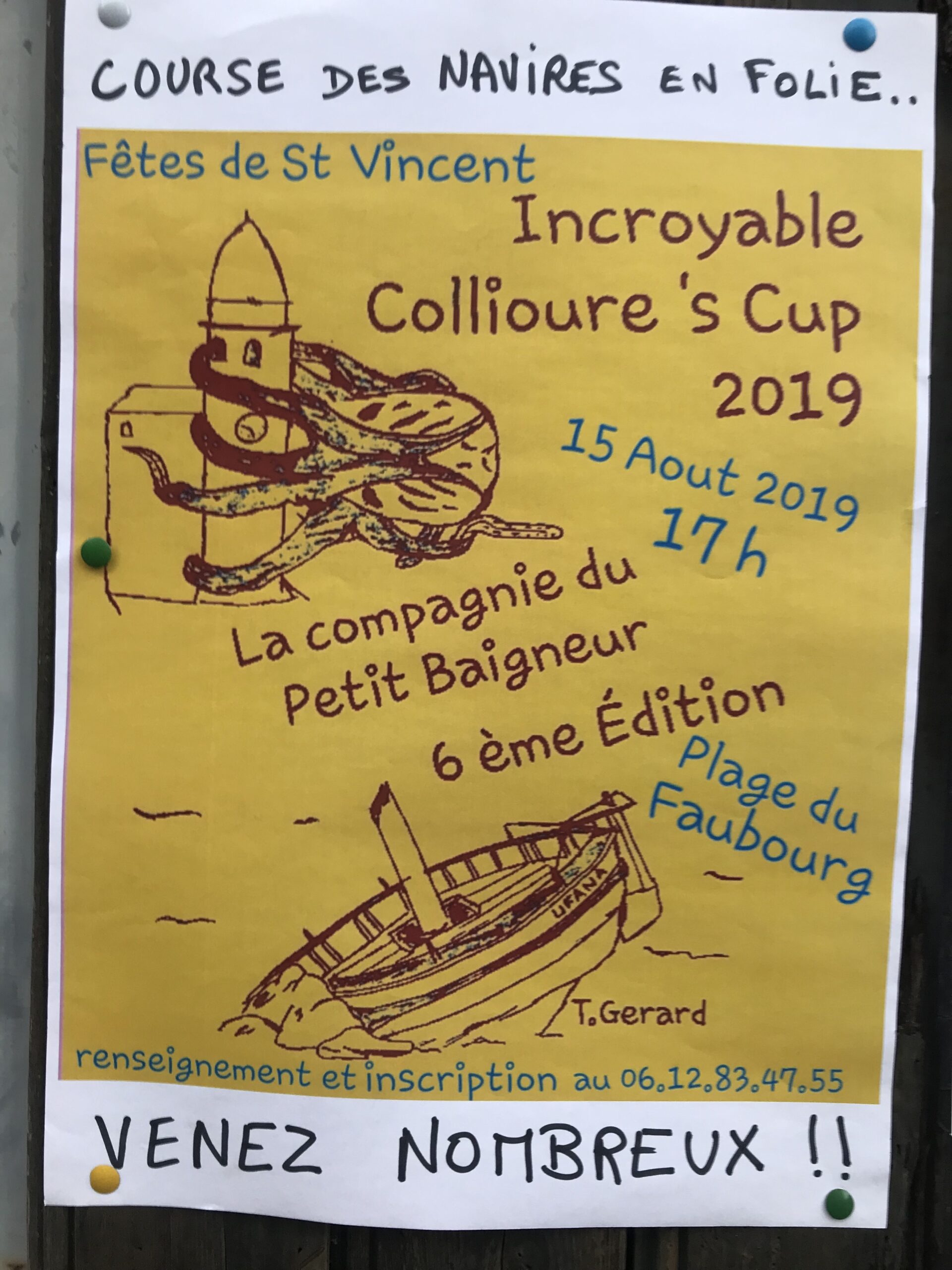

As if signalling that others have also subliminally or intuitively sensed that this display technique evokes the art of cephalopods, David also later began spotting and documenting a series of artistic images that depict the iconic church and tower being amorously embraced and penetrated by giant octopuses (image 2.3 is of a print by local artist La Lori in 2019, while image 2.4 is a poster he pictured on a notice board at the harbour in 2019). To us, such images suggest that the octopuses in question have responded to the seasonal performances as a form of cephalopodic mating display (note that male octopuses have a penis on the end of their ‘hectocotylus arm(s),’ which they use to penetrate the mantle of the female to deliver spermatophores).

3. Eurocentric “Chthulutelevision”

In The Squid Cinema from Hell we namecheck a range of “chthulutelevision” shows, including Sense8 (2015-2018), The O.A. (2016-2019) and Altered Carbon (2018-2020), which demonstrate a high fidelity with the broader event we chart. In naming these three, we admit that there were many others that we simply didn’t have the time or space to do justice to in that volume. For this reason, we felt that a (sort of) sequel to The Squid Cinema from Hell could expand on these sketches, mapping a further range of shows produced within the crumbling imperial center, and which would include: Stranger Things (2016-2020), Dark (2017-2020), Ad Vitam (2018), Watchmen (2019), The Twilight Zone (2019), Devs (2020), Tales from the Loop (2020), and Lovecraft Country (2020). At the time of blogging, we are indeed working up another book that develops a new kind of OOO (object-oriented ontology), and which provisionally is entitled ∞o/Infinite Ontology: Ne∞-Weird Adventures in Chthulumedia, and which should provide us with an opportunity to work through some of the signposted posthuman intersectionalities surrounding race, sex, gender, disability and humanity/animality as we push further towards a quantum model of ‘infinite ontology’ (∞o). This book-to-be also hopes to stand as a prelude to a further edited collection that will explore other species of (non-western) chthulutelevision that stream and screen outside of the fading geopolitical epicenter.

4. Inky octopuses in illustrated kids’ books

Image 4.1 illustrated octopuses

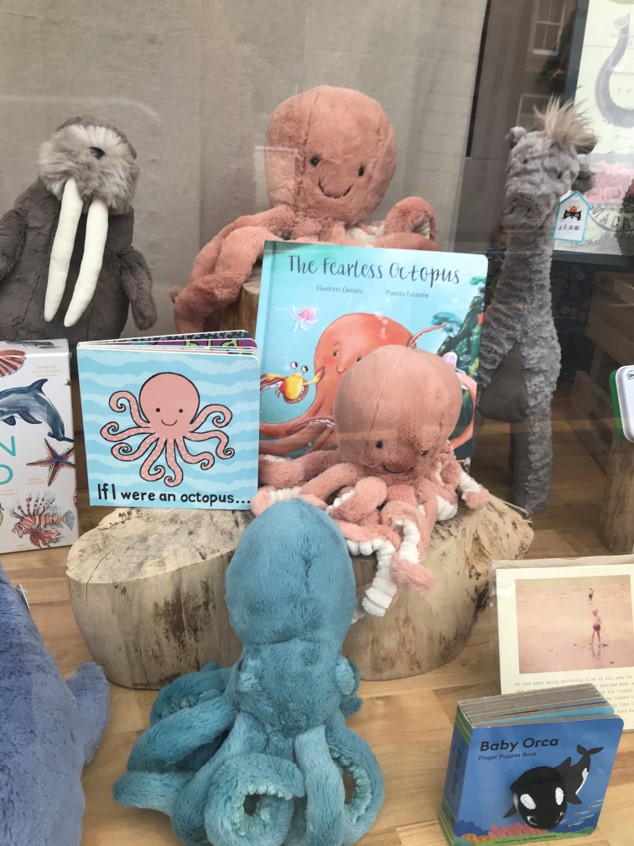

Image 4.2 Shop window

Throughout The Squid Cinema from Hell, we survey a wide range of literary and pulp (e-)works that also eventally channel cephalopods and betentacled monsters. Fictitious graphic novels such as Monstress (2015) are here hung alongside non-fiction books from the self-help genre, such as Jane Gilgun’s The Tentacles of Shame (2015).

For reasons we needn’t fully go into here, David was sent another self-help book of sorts by his sibling during the Covid-19 lockdown… to help with the affected behaviour of his four-year old, who was struggling to adjust to the so-called ‘new normal’ of home-bound familial isolation. David’s sister, who is an infant teacher by trade (and was unaware of her brother co-authoring a book on cephalopods and cinema) here ordered her niece a copy of Lori Lite’s Angry Octopus: A Relaxation Story (2011) to try out. This being an illustrated tale that teaches children to use breathing and relaxation to control their bodies and emotions. And as the title would suggest, it uses an octopus as the personage that needs to learn new anger-management skills. Although the book was not a favourite for the four-year old, it did become interesting to reflect upon the utilisation of these spineless animals as surrogates and tutors for human children—especially in relation to breathing, as we shall see below.

After reading, David also began to reflect on how common cephalopods were nowadays in his daughter’s illustrated library. For, beyond images on her shelves of Hank the ‘Septopus’ (in books spun-off from the Finding Dory (2016) franchise), or the inked out eco-adventures of the Octonaughts (2010-2018), David seemed to encounter these creatures in many other illustrated stories, too. Image 4.1 is a selection pulled out of a shelf when blogging today. These are mainly books that David’s daughter bought at her local charity bookshop.

For us, the ubiquity of octopuses and squids is not something that was true of the children’s books and stories we were read, or began reading, some forty years ago now. There were bears, dogs, cats, rabbits (and other mammals), personified cars, robots … but neither we nor our parents can recall any children’s books with octopuses or squids in them. Something has changed.

In Flusser’s writing in the 1980s he comments that boneless slimy animals such as cephalopods and molluscs typically trigger disgust in vertebrates like us. A fact that he attributes to humans feeling so little empathy or sympathy for them. In the time since Flusser’s writing, a different attitude seems to have emerged. For, many of the books David reads to his daughter, like the better non-fiction ones we enumerate in The Squid Cinema from Hell, now present them as beautiful, caring and intelligent creatures.

5. Tentacular, Volumetric and Mètic Video Games

We remain cognizant of how the tentacles of the video game industry stretch into the worlds of cinema, (sub)culture, economics, entertainment, sport, (bio)politics, pedagogy, psychology and biology among others. Acknowledging this, we felt that we simply didn’t have the time to go into this realm or do it proper justice on this outing. However, we know full well that tentacled monsters abound in contemporary computer games as they do in cinema and television. At least, this is what our colleagues and friends who playfully interact with their software machines are informing us.

Most recently, one colleague joked that while playing on some apocalyptic games on the PS4 during the lockdown, the game Death Stranding presented the bleak, tentacled, oily otherworld of Kojima (see image 5.1), which now ‘looked decidedly preferable to ours…’

David also worked on an earlier (still unpublished) paper with the games studies scholar Paul Martin, exposing a switch from pictorial to volumetric wordings in games and digital media. Although we barely scratched these gaming surfaces in The Squid Cinema from Hell, we comment on how the ludic and mètic transactional tricks and traps of incorporating gaming platforms can be mapped alongside our broader chthulumedia diagram. We sincerely hope that others might plug these gaps and blind spots in the future…. PhD proposals welcome!

6. Chthuluvideos across the multiverse

While David and William spend some time in The Squid Cinema from Hell discussing various music videos by the likes of the Gorillaz and Valentino Khan, there surely is a more concerted study to be done of music videos in relation to tentacular imagery, as well as in the history of music more generally. This might obviously include Pietro Mascagni’s opera Iris (1898), which features the Hokusai-inspired ‘Octopus’ Aria,’ through to the Beatles’ classic ‘Octopus’ Garden.’

The latter in particular could be read as an attempt to escape to a non-human and/or a non-capitalist world, which, by virtue of being ‘in the shade,’ connects with a history of darkness. The notion that the octopus’ garden is a place where ‘we can’t be found’ also brings with it sinister undertones of drowning at sea, something that we might imaginatively connect to the Middle Passage, and the way in which countless African bodies were cast into the darkness of the ocean (and much as numerous non-white bodies built the railway network and the various hard- and sofwares that go into the information superhighway).

Indeed, Kara Keeling has recently written about how Herman Melville’s Bartleby, a literary character who comes to refuse to work, constitutes for Giorgio Agamben a ‘new creature,’ who is also for Gilles Deleuze a ‘new, unknown element… the mystery of a formless, nonhuman life, a Squid.’ Not only does this association chime with Melville’s famous attraction for things oceanic (the white whale from Moby-Dick!), but Keeling goes on in Queer Times, Black Futures to link Bartleby, and by extension the squid, to Black America, in that it, too, is cast into the shade, outside of capital, and that, indeed, many enslaved human beings now ‘can’t be found.’

As much might also be expressed in Azealia Banks’ video for ‘Atlantis,’ in which we see tentacled and other submarine creatures interacting with the rapper in a specifically digital space—thereby suggesting the nexus of race, the digital and the cephalopod in a relatively direct fashion. (What is more, ‘Atlantis’ might itself be a reference to Sun Ra and his Astro-Infinity Arkestra’s 1969 album, Atlantis, with Sun Ra being a point of critical engagement for Keeling in her book.)

William and David take this line of thinking much further in their ∞o/Infinite Ontology book, but with regard to ‘Octopus’ Garden,’ we can identify an appropriative and wishful logic at work in Ringo’s most famous song: in effect, Ringo problematically desires like many a white musician before him to be black.

Meanwhile, Fiona Apple’s ‘Every Single Night’ features the singer with an octopus on her head at certain points in its otherwise rapid montage of Apple covered with snails, walking alongside a giant snail on a New York bridge, and encountering alligators, minotaurs, tortoises with the Eiffel Tower on their back and more.

‘I just want to feel everything,’ Apple sings repeatedly in the song, which also has some shots on the streets of Paris (to maintain our French connection). Perhaps it is by becoming cephalo-cephalous (cephalopod-headed) that Apple can indeed connect with and thus feel everything, living in a world of contact rather than distal observation.

We might also add that Apple not only famously covered the Beatles’ ‘Across the Universe,’ but that she also had a longstanding relationship with Paul Thomas Anderson between 1997 and c2002. We mention this because while cephalopods do not feature prominently in Anderson’s films, as the director of tentacular narratives like Boogie Nights and Magnolia, as well as the octological Hard Eight, and the Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice (with Pynchon featuring in The Squid Cinema from Hell via Gravity’s Rainbow), Anderson is a director par excellence of chthulucinema—something that only becomes more pronounced when we consider his exploration of the oil industry and California in There Will Be Blood, and his deconstruction of masculinity via mushrooms in Phantom Thread.

For more on how mushrooms in cinema play a part in our projects as they vert towards our book on mud, see an essay by William on Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled here: https://aim.org.pt/ojs/index.php/revista/article/view/557. And if you want to see the video for ‘Every Single Night,’ you can watch it on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIlLq4BqGdg. The video for ‘Atlantis’ is also on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yj-xBpQ0CI0.

7. Akira Mizuta Lippit’s Oectopus

If the connection between Apple and Anderson makes it perhaps unsurprising that both of their work features ‘pulpy’ elements, then it is also telling that Anderson was taught during his student days at Emerson College by David Foster Wallace, who also has a minor role in The Squid Cinema from Hell, and whose oeuvre, like Pynchon’s, might more generally be read through a chthulumedia lens (and upon whom we call again in ∞o/Infinite Ontology as a result of his working away from the American ethos of ‘e pluribus unum’ and towards the more multiversal ontology of ‘e unibus pluram’).

This is not to mention literary work by Rita Indiana, Matt Ruff, N.K. Jemisin and William S. Burroughs. To stick to the latter, his short piece, ‘Octopus,’ features in Living With the Animals, a collection of writings edited by Gary Indiana (no relation to Rita). It is a stupendous text, in which the author veers between the brilliance of the octopus, the idiocy of what Burroughs refers to as Homo sap, writing as hiding in ink, zombies, child molestation and nuclear tests… Burroughs even announces Haraway’s notion of making kin when he says that ‘[i]f Homo Sap has any mission, it is to enter into symbiotic relationships with other creatures on the planet—including, of course, biologic mutants and hybrids.’ What a shame, then, that humans spend so much of their time killing and eating animals (‘[a]ll those millions and trillions of years to produce THIS?’).

The Burroughs story also is the focus of Akira Mizuta Lippit’s brilliant essay, ‘Oectopus,’ which we discovered too late for the purposes of incorporating it into The Squid Cinema from Hell. (The essay appears in a journal called Octopus that appears only to have had a single issue, and which also features writing by Eva Hayward, whose work we also admire greatly, but discovered too late for the purposes of The Squid Cinema from Hell.)

What is especially embarrassing is that this is the second time that William has towards the end of a major project discovered a piece of work Lippit that speaks to many of the things that he (here with David) has wished to say on a given topic. With regard to Non-Cinema, for instance, it was Lippit’s fabulous 1999 essay, ‘Three Phantasies of Cinema – Reproduction, Mimesis, Annihilation,’ which made a case for thinking about cinema’s outside, both a supercinema and a non-cinema. But where William was fortunately able to reference the ‘Three Phantasies…’ essay in the conclusion to Non-Cinema, for The Squid Cinema from Hell, the discovery of ‘Oectopus’ came too late.

This omission provides us with a lesson in ongoing humility via humiliation. Why the hundreds of online and other searches did not sooner turn up Lippit’s essay is anyone’s guess—but it bespeaks primarily a failure on our part to hunt and to engage with all of the work that has been written by one of our favourite theorists… because of course they have come to the same topic before us, and all that we thought was so original and insightful is in some senses there in the existing words of another, wiser writer.

Lippit rides many waves in five remarkable pages—and, had we discovered it in time, his essay would have been of great relevance to The Squid Cinema from Hell, especially in our engagements with Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale and Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, where we posit that the cephalopod perhaps in some senses lies outside of Oedipus, or at least switches the sense modality of Oedipus from the eyes to the tongue, the one tentacle that nearly all humans retain from the common worm ancestor that they share with the octopus. But while we think of eyes and tongues, Lippit also introduces us to how the cephalopod (literally ‘head-foot’) is all about feet.

For, what is in particular exciting about Lippit’s essay is how he crosses the octopus with Oedipus, hence ‘Oectopus’ as the title, weaving a beautiful theory about how Oedipus’ bad foot (oidipous) resonates with the eight-footed octopus, and which in turn links to the Riddle of the Sphinx, which is all about the changing number of feet of the human (four in the morning, two in the afternoon, three in the evening). Given its changing feet, the human clearly changes form as the octopus changes form—since the latter of course is a soft mollusk and has no bones (and thus is informe, or what in the digital age we might think of as information). Perhaps an eight-, or even nine-footed being is what the human will becomes as it mutates into new life (with the renewed interest in walking, especially as it is brought to bear in work in the psychogeographic tradition, suggesting also that humans are beginning to think with their feet, as much as with their heads, since we are cephalo-pods, too)…

As we gear up to (or rather, as we have written three quarters of the first draft of) ∞o/Infinite Ontology, we promise of course to make good on our oversight of Lippit, as well as various other texts.

8. Breathing underwater

As we write our new book, what seems clear to us is that critical race theory and cephalo-thinking have much in common, as the reference above to Kara Keeling’s work implies; and this is indeed perhaps the chief direction in which we take our work in the upcoming book, having introduced it as a point of critical engagement towards the end of The Squid Cinema from Hell.

But if we, by which we mean we human beings as opposed to we mere writers, are to evolve into eight-, nine- or any number of multi-footed and ever-changing and informed creatures, then one thing is for sure: we shall have, like the octopus, to learn to breathe underwater.

The year 2020 will, for as long as it is remembered, be remembered for Coronavirus and the death of, inter alia, George Floyd. Both are of course linked by an attack on the respiratory system—something that we see taking place more generally as the oceans rise, as our air becomes more polluted, and as what Peter Sloterdijk would call the ‘atmoterrorism’ of capital continues apace.

If we have any 2020 vision (or feeling), then, it will be that we must learn to breathe underwater, to find new, previously impossible ways to breathe, since capital, especially in its racial politics, prevents humans from breathing.

And if we look at critical race theory, especially work from Black Studies, then we can find numerous theorisations of the human breathing underwater, having salt water in their veins, and so on.

And so it is in this direction that we are taking our work at present, as we continue to walk on our eight and more feet towards our mud project, which will indeed follow on from the cephalopods in our understanding of chthulumedia, or the (digital) media of/as the chthulucene.

We do this not because it simply is ‘timely’ or politically correct; rather, it is work in what Achille Mbembe might identify as the ‘necropolitical’ tradition that the most vital theorizing is today taking place, and which provides a possible future for what humanity may yet become. In some senses it stands to reason: as the human becomes the non-human, it is of course by engaging with theories of the non-human and that which has been relegated to the outside of humanity (Blackness) that we can begin to get a sense of our future.

But in another sense it is important that the animal, including the cephalopod, is not simply an excuse for us as scholars and as human beings not to look at race (in that we in the overwhelmingly white academy would rather think and write about animals, plants, machines and objects than we would about non-white humans, which might be one possible interpretation of the ‘animal,’ the ‘plant,’ and the ‘object’ turns alike—as Zakiyyah Iman Jackson has suggested in her recent work).

In a world increasingly understood to be built upon anti-blackness, it is only by venturing into blackness that we can find new, other worlds, which are not anti-black and where everyone can breathe. It is our duty, then, to pursue this line of thought. In the octopus’ garden, in the shade, we scholars and other human beings might find (non-)humans who can breathe underwater, who can help us to discover a more feeling world, and who can help us understand that we do not need an animal turn, a plant turn or an object turn. Indeed, as an invertebrate, the cephalopod has no back and cannot turn as such. In this sense, perhaps the cephalopod, especially when read through critical race theory, can help us to conceive a new, better, finally human world.

William Brown is an Honorary Fellow in Film at the University of Roehampton, London. He is co-author of The Squid Cinema from Hell: Kinoteuthis Infernalis and the Emergence of Chthulhumedia with David H. Fleming (EUP, 2020), and the author of Non-Cinema: Global Digital Filmmaking the Multitude (Bloomsbury, 2018), and Supercinema: Film-Philosophy for the Digital Age (Berghahn, 2013). William is also the maker of various no-budget films and film-essays, and currently is working on two books, one about ‘infinite ontology’ and ‘chthulutelevision,’ and another about mud and media.

David H. Fleming is Senior Lecturer in Film & Media at the University of Stirling, Scotland. His interdisciplinary research often engages the outsides and intersectionalities of images, technology, events and philosophy. He is co-author of The Squid Cinema from Hell: Kinoteuthis Infernalis and the Emergence of Chthulhumedia with William Brown (2020), and Chinese Urban Shi-nema: Cinematicity, Society and Millennial China (2020) with Simon Harrison. He is also the author of Unbecoming Cinema: Unsettling encounters with ethical event films (2017). David is currently working on an essay film about Hibs and Cinema, and books about infinite ontologly and ‘chthulutelevision,’ and mud.