Participants in the protests following the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota have emphasised historical continuity in the experience of racist oppression in the United States. In my recent publication, Anxious Men: Masculinity in American Fiction of the Mid-Twentieth Century, I consider writings from the middle of the twentieth century by African American authors – James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Chester Himes, and Anne Petry – that bear witness to this history. For example, in Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952 [Penguin, 2001]) the shooting by a policeman of Tod Clifton, an unarmed African American, is a trigger for riots in Harlem.

Throughout the novel, Ellison shows how violently enforced racist oppression is part of the everyday experience of African Americans. Yet the stories told by these writers are also important in representing the significance of the lives of black Americans in the period. They also show how the culture of African Americans is integral to the history and identity of the United States.

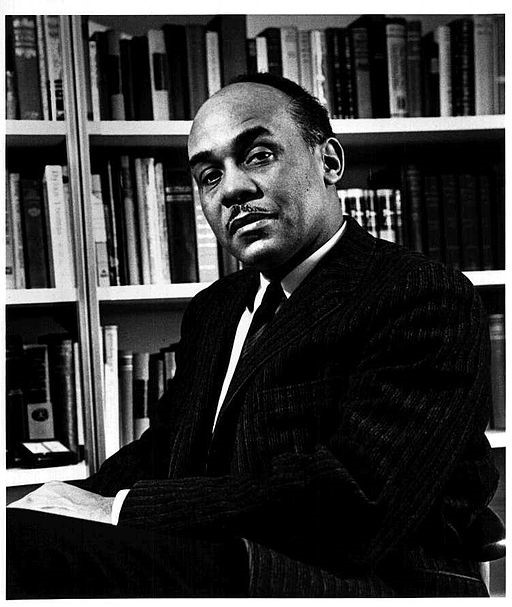

Photo: United States Information Agency staff photographer; Public domain

Race and black masculinity

Issues of race intersect with issues of gender, and it is notable that it is black men who are most frequently the victims of police violence. The characterisation of black men is described by Simukai Chigudu, an academic at Oxford University, as an ‘ugly stereotype’ – ‘hot-blooded, impervious to reason and unworthy of serious engagement’ (The Guardian,12 June 2020). Moreover, ideological justification for slavery dehumanised all black Americans. It is against such racist stereotypes that Ellison’s narrator and protagonist struggles as he seeks to develop an adult male identity.

Ellison’s subtle and ironic narrative exposes the invisible man’s naivety as he seeks male exemplars on which to model his behaviour. Although he has a belief in the American values of ‘hard work and progress and action’ (Invisible Man, 576), he places his trust in the false promises of charlatans, and ignores older and wiser African American men, who are rich in the experience of black American culture and history.

None of these latter is more significant than his grandfather, who poses a conundrum on his deathbed. He says that he regrets giving up his gun during Reconstruction and advises his family ‘to keep up the good fight […] our life is a war’, in which he has been a ‘traitor’ (Invisible Man, 16). However, this is accompanied by an apparent contradiction, ‘I want you to overcome ’em with yeses, undermine ’em with grins, agree ’em to death and destruction, let ’em swoller you until they vomit or bust wide open’ (16). It is this puzzle that the invisible man grapples with through the novel. If racism is founded on, and maintained through, violence, how is it to be countered – through violent resistance, or some other action? In the end the invisible man recognises his own humanity as an individual and resists conformity – ‘diversity is the word’ (577).

James Baldwin, ‘Notes of a Native Son’

In ‘Notes of a Native Son’ (1955 [Beacon Press, 1957]) – an essay that reflects on his relationship with his father – James Baldwin describes how his experience of racism has helped him understand and empathise with the bitterness he sees in his father. Baldwin worked in war production in New Jersey in 1942–3 and suffered continuously from racism at work and in public spaces. The culmination of this occurred during his last night in New Jersey when he was told in the ‘American Diner’, ‘We don’t serve Negroes here’ (‘Notes of a Native Son’, 95).

Baldwin then describes his nightmarish experience after going back out onto the street, perceiving a sea of white faces moving against him and wanting to crush them in response. He then goes into ‘an enormous, glittering, and fashionable restaurant, in which I knew that not even the intercession of the Virgin would cause me to be served’ (96). Again, he is told that they ‘don’t serve Negroes’ and reacts by hurling a glass of water at the waitress and shattering a mirror.

In retrospect, Baldwin regards himself in this period as having ‘contracted some dread chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowels’ (94). But this is not an individual affliction: ‘There is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood’. It is this perception that allows Baldwin to see how his father’s bitterness and paranoia is the consequence of a life spent in a racist society.

Photo: Allan Warren; Wikimedia Commons

Ellison’s and Baldwin’s representation of racist oppression and violence in the 1940s has relevance today and their writing poses the same question that is now being asked with such urgency: how can endemic racism and its associated violence be eliminated? Both writers are clear about the psychological damage caused by racism. In Ellison’s novel racism dehumanises his protagonist, until he recognises this and is able to claim humanity for himself. Baldwin’s father reacts by facing the world with hostility and paranoia. Observing his father and acknowledging his own ‘rage’, which he believes is self-destructive, Baldwin sees his choice as between ‘living with it consciously, or surrendering to it’. In an echo of the invisible man’s conundrum, he proposes the solution of holding in oneself two opposing ideas – to accept life as it is, while fighting injustice with all one’s strength.

About the Author

Clive Baldwin is Honorary Associate of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The Open University, and formerly Associate Dean for Learning and Teaching in the Faculty of Arts, The Open University. His publications include recently published Anxious Men, published with Edinburgh University Press (2020), a review of Maggie McKinley, Masculinity and the Paradox of Violence in American Fiction, 1950-75 (2016); ‘Digressing from the point: Holden Caulfield’s women’ in Sarah Graham. J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (2007); and ‘“A certain ill-defined disgrace”: masculinity and sexuality in Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach’ (2011).