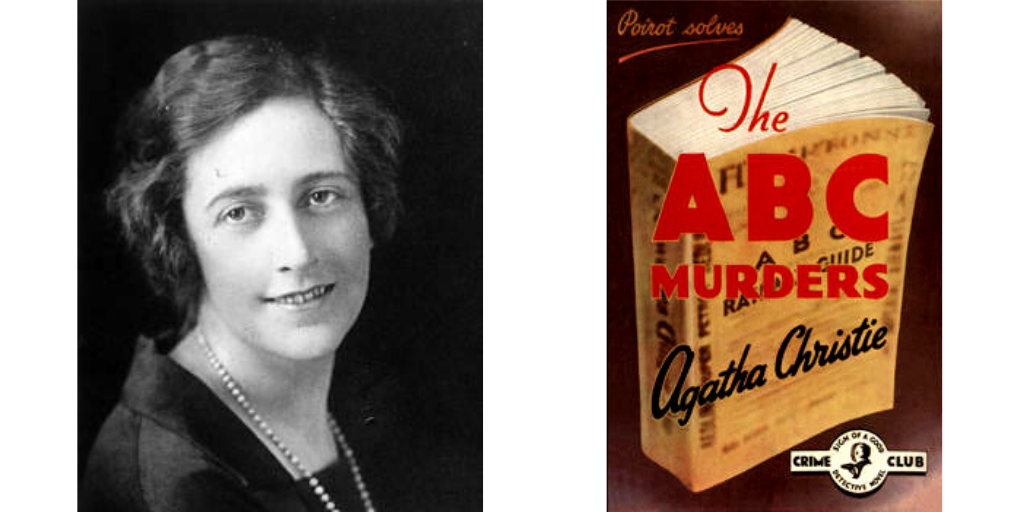

I came to crime fiction studies through the back door. Like many people, I grew up reading mysteries. Franklin W. Dixon’s Hardy Boys series was an early favourite – I coveted the small blue hardcovers with a greedy passion, and aspired, though never achieved, to a complete collection. I had no idea, of course, that Dixon was himself a fiction, the pen name for a series of ghost-writers pumping out mysteries for the Stratemeyer Syndicate (which sounds, come to think of it, more like a gang than a publishing house). As I got older, I moved on to Agatha Christie – my grandmother had a pretty solid collection of her novels, and they did much to make long family visits during the holidays more bearable.

As I began to take reading more seriously, however, I pretty much gave up on crime novels. I read as widely as only the young can (and no doubt as superficially – but still, is there anything more glorious than the voracious literary gluttony of a young reader who’s just realised how good books are?), but not much of it was crime fiction. Even when I did read fiction about crime and detection, Dickens’ Bleak House, say, or Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, I didn’t think of what I was reading as crime fiction – I was reading Literature with a capital ‘L’.

Years passed and I eventually started work on my PhD (at the University of Edinburgh, as it happens). My research area was modernism in general, and Virginia Woolf in particular, but when I wasn’t grappling with The Waves or The Years, I read as widely as I could in the inter-war period – and a lot of that was crime fiction. There was Christie again, and Dorothy L. Sayers, and Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, and Georges Simenon and so many others. Gradually it occurred to me that these writers were every bit as interested in exploring the shifting social and ethical landscape of their era as any of the canonical modernists, and every bit as interested in experimenting with the potentialities of their form. They were, in other words, every bit as interesting as authors whose works circulated in a much more rarefied critical atmosphere.

I have never stopped reading, and thinking and writing about, works of fiction from the ‘high culture’ camp. But I’ve also learned to love the many rewards of works that operate at the other end of the cultural spectrum: for the straight reading pleasure of a well-told tale of mystery and detection or crime and punishment; for the social insight, historical and contemporary crime fiction offers; and for the sheer literary brilliance of many works dismissively labelled as popular fiction. I’ve also paid much more attention to what Michael Chabon calls ‘the borderlands’, or the places on our conceptual map of the literary world where the boundaries between high and low, elite and popular, blur.

This gradual entry into the world of crime fiction has been hugely rewarding. I’ve met brilliant scholars at crime fiction conferences (like Fiona Peters’ Captivating Criminality series, associated with the International Crime Fiction Association), discovered wonderful authors (if you are looking for something new to read, take a look at my compendium 100 Greatest Literary Detectives for exciting possibilities from around the world), and, in a modest way, contributed to the very lively ongoing scholarly discussion that continues now in the pages of our new journal Crime Fiction Studies.

At the same time, the fact that it took me so long to recognise that the works of authors I loved deserve – and reward – the same kind of attention as their more ‘reputable’ literary contemporaries fascinates me. How can something as intangible as cultural prestige impose such effective blinders on a reader? My contribution to Crime Fiction Studies 1.1, ‘Contemporary Crime Fiction, Cultural Prestige, and the Literary Field‘, is part of a larger attempt to answer this question. It builds on fundamental work done by James English, whose book The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value is a touchstone in the field, and on work I’ve done with Colleen Kennedy-Karpat on questions of cultural prestige in relation to adaptation (Adaptation, Awards Culture, and the Value of Prestige). In the essay, I try to do two things: first, to trace out the theoretical underpinnings governing the circulation of genres within a larger literary system, and, second, to assess the changing cultural status of crime fiction in the twenty-first century using a number of relatively objective measures, from broadsheet reviewing to literary festivals to, most importantly, prize culture. The results? Well, I’ll direct you to the essay as a whole – I hope you enjoy it!

By Eric Sandberg

Crime Fiction Studies is a brand new journal publishing twice a year. The first issue, Crime Fiction Today, is out now. Find out how to subscribe as an individual or as an institution, and how to recommend the journal to your library. You can also sign up for Table of Contents alerts to keep up to date with all of the latest content.