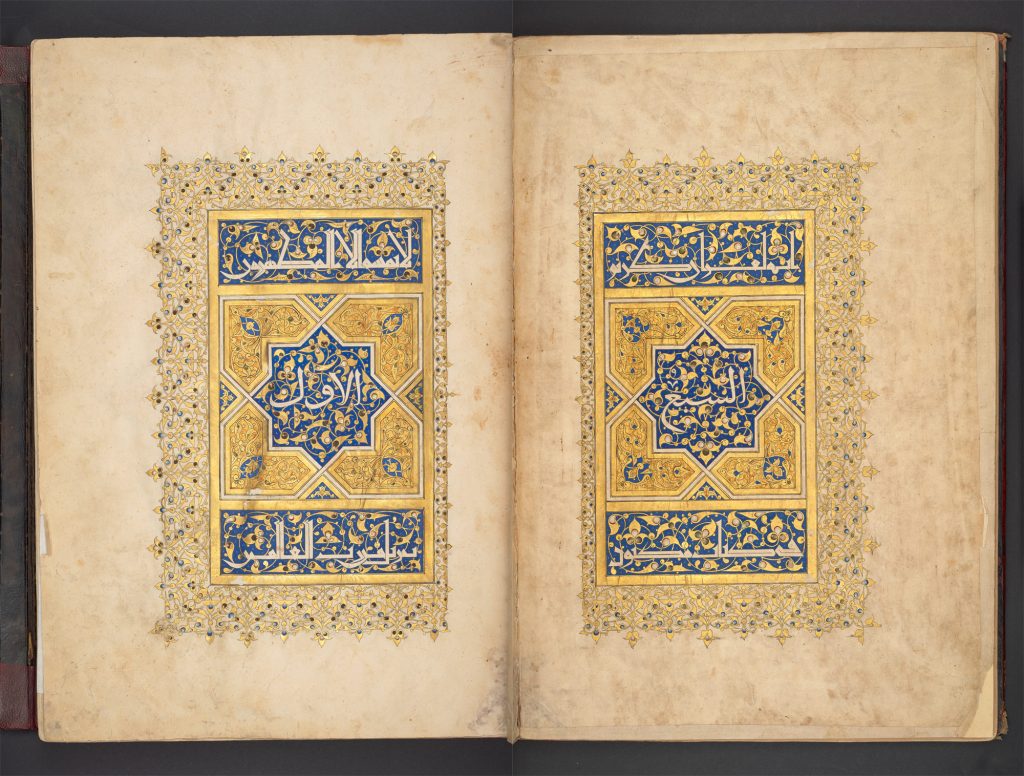

Upon hearing the phrase ‘medieval Arabic manuscript’, you might think of the kind of high-end object that we often see on the websites of museums and libraries, like Sultan Baybars’ Qur’an. However, there is a whole world of low-end, pedestrian and not-very-beautiful medieval Arabic manuscripts – a world that has gained much less interest. These are small, thin booklets, often only of 20 pages. Because they were small, they were very handy: you could easily carry them around, they were cheap to produce and you didn’t even need an expensive binding. Since they were quite mundane objects, people were strikingly creative about how to produce or rework them. Here are the three best things I have come across so far.

1. Consider recycling to make a nice, cheap cover

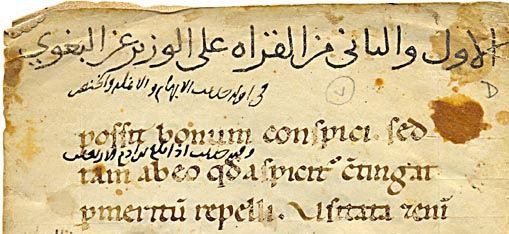

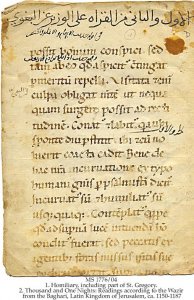

Can’t afford to bind your medieval Arabic manuscript in elaborate leather bindings? One popular technique was to reuse the pages of a fancy old parchment manuscript. They were not only easy to get but also very sturdy. Look at this Latin homiliary that a Syrian scholar reused 800 years ago as a title page for his booklet.

2. Out of paper? Rummage through your parents’ belongings to find something suitable

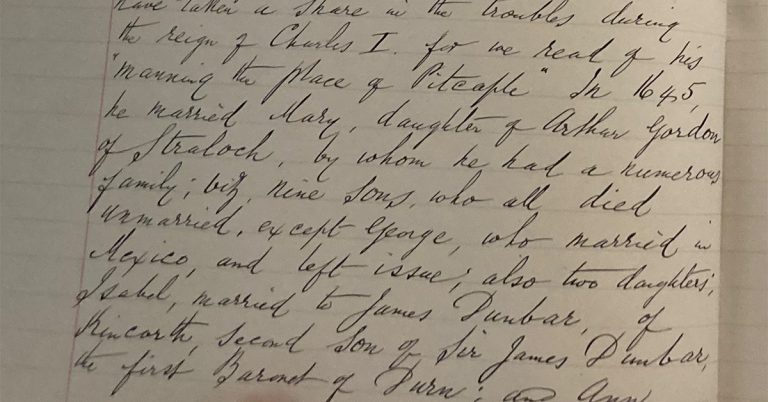

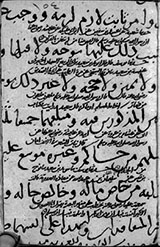

Paper tray empty again? Let’s see if there’s anything else you can use. Specifically: your parents’ marriage contract. It’s huge, the paper is of good quality and the scribe left a lot of space between the lines to make it a seriously sumptuous document. Just cut it into 16 pieces, as a scholar did 850 years ago, and write your own text between the lines.

3. Create a fat volume of medieval Arabic manuscripts (or 100 of them)

Worried about what will happen to those unbound and fragile medieval Arabic manuscripts circulating in your city? You should be: these booklets were an endangered species. Once their texts fell out of scholarly fashion they quickly disappeared. Owners were not that concerned about preserving them compared to the luxury items on their shelves. So why not take drastic action to keep them safe?

One Damascene scholar 500 years ago did just that. He saw that a lot of these medieval Arabic manuscripts were being pulped or sold on the city’s flea-market as scrap paper. So he went on a massive shopping spree and bought thousands of them in a cultural heritage safe-guarding operation. When he got back home he sat down with his close family (it was seriously large) and embarked on a binge-reading marathon.

Finally, he would bind dozens of these booklets together into one thick volume to protect them. He created more than 100 massive, properly bound volumes and placed them into the library of a madrasa overlooking the city. In this way he created a marvellous monument to Syrian book culture that otherwise would have vanished. This monument is still in Damascus (though some manuscripts are in libraries around the world) and it is a unique testimony to a rich and messy world of books long gone. If you want to know more, the full story can be found in my new book, A Monument to Medieval Syrian Book Culture: The Library of Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī.

By Konrad Hirschler

Konrad Hirschler is Professor of Islamic Studies at Freie Universität Berlin. His latest book is A Monument to Medieval Syrian Book Culture: The Library of Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī (available as an Open Access ebook from Edinburgh University Press).

More from Konrad Hirschler about the Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī family’s epic medieval Arabic manuscript reading binge:

- ‘Binge Reading in Fifteenth-Century Damascus’ on DYNTRAN: Dynamics of Transition

- ‘The Many Lives of a Medieval Library’: Episode 380 of the Ottoman History Podcast

Image credits

‘Volume one of a seven-volume Qur’an commissioned by Rukn al-Dīn Baybars, later Sultan Baybars II’ via British Library.

Homiliary, Including Part of St. Gregory | Ms 1776/04 via The Schoyen Collection.

Marriage contract (large script) with the son’s text between the lines. Damascus, National al-Asad Library 3748, fols 153b/154a. © National al-Asad Library.