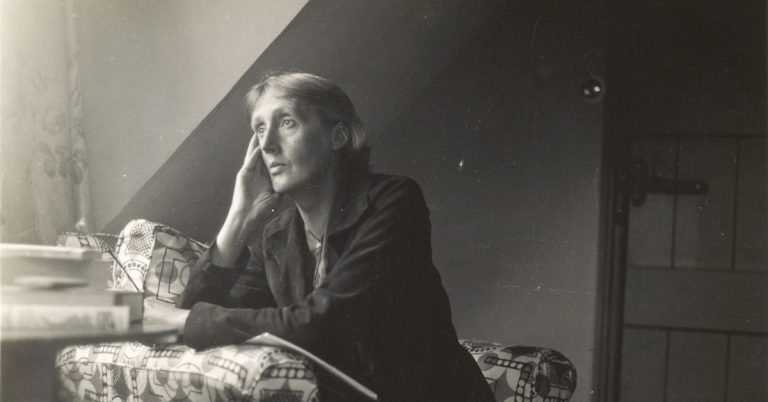

Once known primarily as the author of ‘twee’ children’s books about fastidious mice and naughty rabbits, Beatrix Potter has gained recognition in recent years for her wide-ranging accomplishments as a conservationist, mycologist and scientific illustrator. In the 1890s, before embarking upon her career in children’s publishing, Potter painted hundreds of illustrations of mushrooms and authored a scientific paper on the germination of fungal spores.

Beatrix Potter’s Mycological Aesthetics, my recent essay in Oxford Literary Review 41.2, charts the affinities between Beatrix Potter’s mycological research and her children’s books to highlight the centrality of the child within ecological thought. As Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing notes in The Mushroom at the End of the World, mushrooms give shape to the tentacular forms of our ecological entanglements, leading us toward an ‘arts of noticing’ as a means of survival. By considering how Potter’s work unravels the binary constructs that have underwritten human exceptionalism, I argue for the significance of diminutiveness and whimsy to a politics that cares for nonhuman life.

Beatrix Potter used her brother’s microscope to illustrate her mushroom specimens, a technique that not only lent her pictures a high degree of scientific accuracy, but gave them an iridescent quality in which the amplification of small details produces a sparkling vitality.

The miniature worlds found in Potter’s animal tales might be thought to conjure up a similar effect. Designed to fit neatly into a child’s small hands, her children’s books find vibrant life in societies of frogs, mice, rabbits, squirrels and other small creatures, worlds that often go unnoticed under the dominance of conventional anthropocentric modes of perception. By placing her scenes inside a circular vignetting surrounded by the white space of the page, Potter created illustrations that invoke the sensation of peering inward through a microscope to discover a tiny, fairy-like realm.

This combination of attention and imagination also transpired in the care with which Beatrix Potter illustrated both her animal characters and their human clothing, adhering to the correct anatomical structures of her subjects while outfitting them in fanciful ensembles. The amusing juxtapositions that result—Jemima Puddle-Duck in her bonnet, Jeremy Fisher in his skirted coat and breeches—evince what Jane Bennett calls ‘a touch of anthropomorphism’, indulging in a measure of whimsy to combat the violence of rationalist normative discourses and to envision new modes of relationality and interdependence.

Of course, Beatrix Potter is just one of many artists and thinkers to blend attention and imagination in ways that illuminate our ecological entanglements, and her work cannot be fully extracted from British imperial nostalgia. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a plant biologist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, writes in Learning the Grammar of Animacy about how she felt moved upon learning the indigenous Anishinaabe word ‘puhpowee’, which means ‘the force which causes mushrooms to push up from the earth overnight’. Kimmerer reflects, ‘In all its technical vocabulary, Western science has no such term, no words to hold this mystery’.

Growing up as a half-Japanese American in California’s Silicon Valley, during a time when cherry orchards were being paved over to make room for Apple and Google, I found myself enchanted by Potter’s adorable creatures, perhaps as an antidote to what I perceived as a world expanding far too fast. And I have to admit that I still find something charming about the miniature worlds that Potter dreamed up over a hundred years ago, their mixture of a quaint pastoralism together with an unflinching depiction of life’s harsh realities. (Let us not forget the ‘accident’ that caused Peter Rabbit’s father to be ‘put in a pie’.)

This past summer, as I was walking down a street in Tokyo’s fashionable Shibuya ward, I was arrested by a display of Peter Rabbit stuffed toys accessorizing the window of a bank. Then I visited a hedgehog café where tourists were snapping pictures of the sleepy animals amid kawaii (‘cute’) dioramas, including many scenes reminiscent of Potter’s country settings.

Today, I study cuteness as a politicized global aesthetic produced by the transnational flows of racial capitalism, and I hope to someday write about Potter’s popularity in postwar Japan. But this does not mean that part of me doesn’t continue to believe in the magic of small things: that they help connect us to one another, and that they might even show us ways to imagine care across scale and difference.

By Erica Kanesaka Kalnay

Erica Kanesaka Kalnay is a Ph.D. Candidate in English Literary Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she researches children’s literature, toys and Asian diasporas. You can find her online at ericakanesaka.com.