My new book on the egalitarian sublime has almost no sport in it. I avoid it for political reasons. As entertainment, sports are the bread and circuses of our age: examples of the negative power of manufactured sublimity.

The need to understand and resist this power is behind the search for an egalitarian sublime. Can the values elevated by sublime works and deeds lead to a more equal society, or, as in Nietzsche, must they always divide greatness from ‘the masses’?

How the sublime shapes our values

‘Sometimes you really do have to stand and watch – and maybe gawp a little too. The best athletes in every sport give us a glimpse of something else, a remix of the usual physical laws.’

Barney Ronay

To call something sublime – to make something sublime – is to shape the values we take to be superior. This changes the lives of those living by those values. But that change is not consistent. It always divides winners from losers, leaders from followers, masters from slaves, players from spectators.

Animals have been losers in the search for the sublime and resulting divisions. They rarely take centre stage, erased from landscapes and by technology, or made to carry all too human meanings and feelings.

In traditional versions of the sublime, humans stand alone against troubling grandeur – the sportsperson highlighted against holy mountain or void. This sublimity inevitably downgrades other humans, like Kant’s ‘good and otherwise sensible Savoyard peasant who did not hesitate to call anyone a fool who fancies glaciered mountains.’

Every sublime sporting moment relies on countless helpers: sherpas, lift operators, drivers, farmers, pilots, groundskeepers, health professionals, cleaners and mechanics. They aren’t in the sublime pictures. Neither are ordinary players and enthusiasts.

Kant, sports and the sublime

The sublimity of sports for spectators bears many resemblances to Kant’s philosophy of the sublime. The sublime move in sport goes beyond the merely beautiful. We cannot comprehend it – hence the need for the slow-motion replay. It combines astonishment and attraction: the painful awareness that it would be impossible for you to achieve this feat; your desire to copy it regardless. This sporting sublime is political, as it is in Kant, in presenting us with the possibility of new values.

But the sporting sublime is a distortion of the Kantian sublime that falls short of Kant’s progressive aims for humanity. In sport, the sublime is a contribution to victory – the sublime goal – but for Kant, the sublime cannot have a purpose. Kantian sublime excess can never be attained; the superior values it generates are elsewhere, in morality and politics. In spectator sports, the sublime is picked apart, exploited, copied and negated. The Kantian sublime prompts a turn to reason: we are free to choose universal laws for the whole of humanity because we can overcome the sublime. Sport-as-spectacle is not universal: it focuses on a few extraordinary individuals, themselves actors in a well-regulated and exploited show.

Sport and an egalitarian sublime

For an egalitarian sublime, neither Kant nor elite sport indicates the right way. Sport encourages values of victory, competition, ranking and effort deployed within well-defined rules and for limited outcomes. Politically and existentially, we require exactly the opposite. We should overcome the desire to vanquish. Competition must give way to cooperation and ranking to multiple ways. Our efforts should be critical of established law, rule and money.

Similarly, the Kantian philosophy of the sublime leads to the imposition of falsely universal values – only including Savoyard peasants or Sherpas if they bend to a particular version of the sublime and to its consequent morality. The sublime feeling is not universal. It varies from group to group and from individual to individual. Why should the austere sublime of northern mountains and Kant’s protestant morality be imposed as universal for all?

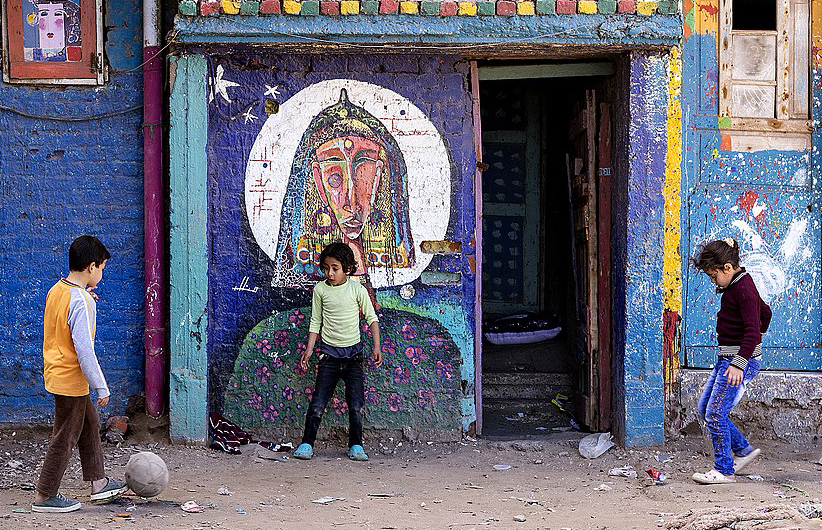

The multiplicity of experiences of the sublime suggests a different role for sport. The sublime can be egalitarian but it must lose its scale, grandeur and elitism. When practised rather than watched, sport is different: sublime, multiple, anarchist and egalitarian. We each find ways to enjoy it and share it with others, inventing new sports and subverting old ones, playing in dusty back yards or surfing railings under bridges. It’s hard to grasp spin in table tennis, or to tumble turn, or to pull a rope in unison. But we get there and we change for the better as we do.

By James Williams

James Williams is Honorary Professor of Philosophy and member of the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalization at Deakin University.

Did you enjoy ‘Sublime goals? Sport and the egalitarian sublime’? You might like these other posts by James Williams:

- For F’s Sake: Theresa May, Falling Letters and the Philosophy of Signs

- Behind Red Doors – Signs, Process and the Political

Image credits

‘Lionel Messi World Cup final…‘ (adapted) by Jimmy Baikovicius via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

‘The Monarch of the Glen‘, Edwin Landseer, 1851 via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

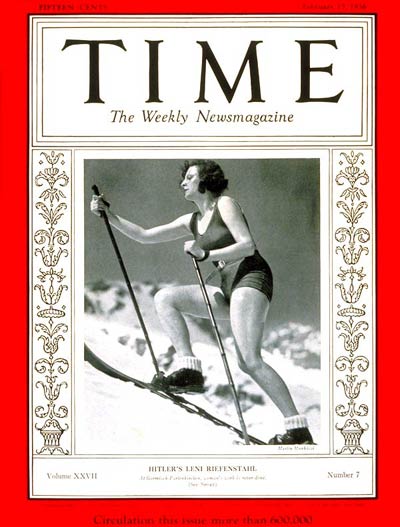

‘Leni Riefenstahl on Time magazine 1936‘ via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

‘The Volunteers London 2012…‘ by Peter Mooney via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

‘Messi vs Nigeria1‘ by Кирилл Венедиктов via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

‘Ready to shot‘ (cropped) by Mohamed Hozyen Ahmed via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)