The Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict is one of the most embittered territorial disputes in the world

In the early hours of 2 April 2016, President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan and President Serzh Sargsyan of Armenia were returning from a nuclear security summit in Washington. At the same time as the presidents’ aircraft wound their respective ways home, fighting broke out in Nagorny Karabakh, the South Caucasian territory disputed between the two states. The Armenian–Azerbaijani ‘four-day war’ that followed claimed more than 200 lives and briefly focused minds on one of the world’s most embittered territorial conflicts.

Just over two years before April’s ‘four-day war’, I had left my job as a peacebuilding practitioner to research a book on the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict. I was tired of the default term, ‘frozen conflict’, used to describe it (and others in the post-Soviet space). As a catch-all term for territorial disputes from the River Dniestr to the Caspian Sea, ‘frozen conflict’ to me suggested all the wrong things. It suggested a residual conflict left over from an earlier age, the complacency of defining conflicts as inactive and agent-less, and the convenience of streamlining richly storied places into a slick and marketable routine about power plays by Moscow against Western interests.

The dawn of the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict

To be sure, the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict retains a lot in common with others in post-Soviet Eurasia. Independence fell upon Armenia and Azerbaijan with force majeure in 1918 after the collapse of the Russian Empire. Improvising nation-builders in both communities confronted a dual legacy: the absence of historically recent sovereign traditions providing territorial templates for new states, and thoroughly intermingled populations. Over the 1918–20 period Armenians and Azerbaijanis came to blows in three borderland areas of what was then referred to as Transcaucasia: Nagorny Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhichevan. Re-absorption into their northern neighbour, reconfigured as a revolutionary Marxist state under the leadership of V.I. Lenin, meant that the resolution of these conflicts was subordinated to Soviet regime-building. Soviet nationalities policy divided up territories in an effort at compromise dependent on the reality of a single, totalitarian power vertical. Nagorny Karabakh, an Armenian demographic island within Soviet Azerbaijan, was granted autonomy, although in practice the rights conferred were only symbolic.

The progression of the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict

As the Soviet power vertical began to crumble in the 1980s, the enforced compromises of the 1920s began to unravel. An Armenian movement for the unification of Armenia and Nagorny Karabakh was almost immediately overrun by intercommunal violence in 1988. Against the backdrop of the imploding Soviet Union, violence that began with stones and hunting rifles escalated to full-blown modern war fought with disbanded Red Army materiel. As elsewhere in the former Soviet Union, secessionists won, and Nagorny Karabakh, alongside a large swathe of adjacent occupied territories, was held by Armenian armed forces by the time of the 12 May 1994 ceasefire.

Through the 1990s and early 2000s the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict lingered, like others in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transdniestria, in the Eurasian margins. But as these other conflicts became increasingly framed as symptoms of wider Russian-Western rivalry, the Armenian–Azerbaijani dispute increasingly became an outlier. Unlike conflicts involving Georgia and Ukraine, the dispute remained free of the tripwires of aspirations to NATO or European Union membership. It was also the only context where Russia sought friendly relations with both belligerents. Consequently, Russia had no clear winning outcome in a war between them. This made Armenian–Azerbaijani the only dispute where Russian interests actually aligned with Eurpean and US in preventing renewed war. And it was also the only conflict in Eurasia where the losing side in the 1990s subsequently transitioned to becoming the preponderant party in terms of military purchasing power and capacity.

The Aftermath

Abandoned buildings in Shusha (known as Shushi in Armenian sources), the historical capital of Nagorny Karabakh.

They bear quiet testimony to the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict.

From the late 2000s, the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict took on the attributes of an enduring rivalry. This is a peculiar form of interstate conflict known for both its propensity to violent confrontation and resistance to resolution. The dispute has increasingly more in common with long-term, militarised rivalries elsewhere in the world. Other examples include the India-Pakistan, Arab-Israeli and North-South Korean rivalries. The conflict’s continuing capacity to threaten regional peace derives from converging factors at domestic, leadership, strategic regional and systemic levels. The cultures of geopolitics in Armenia and Azerbaijan, the normative preferences of their regimes, the power strategies they pursue, and the equilibrium among outside powers that the rivalry between them sustains – all of these play a part.

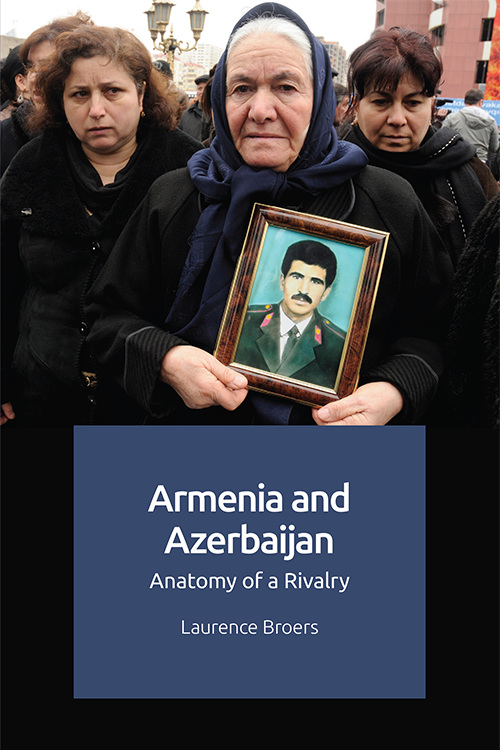

By Laurence Broers

Laurence Broers explores the above discussed (and many other) factors in his book, Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. He argues that the Armenian–Azerbaijani rivalry is neither frozen nor pliable, but a surprisingly – if imperfectly – stable configuration that has outlived a succession of distinct regional and global conjunctures, from the collapse of the Soviet Union, the false dawn of Russian-Western rapprochement in the 1990s, new Russian-Western confrontation from the late 2000s and the onset of a multipolar era that followed.

Dr Laurence Broers is a Research Associate at the Centre of Contemporary Central Asia & the Caucasus, School of Oriental and African Studies. He is the co-editor of three volumes, most recently, with Galina Yemelianova, of The Routledge Handbook of the Caucasus. He is also the co-founder and co-editor-in-chief of Caucasus Survey (Taylor & Francis). He has extensive professional experience working in policy analysis and managing Armenian–Azerbaijani peacebuilding initiatives at the civil society level.

Cover image credit

- ‘View over Khudaferin…‘ by Adam Jones via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)