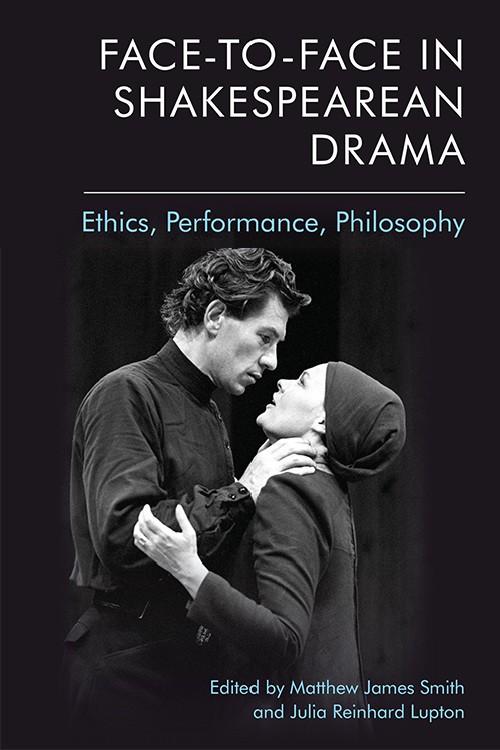

JRL: Hi, Matt. This volume began as a seminar at the Shakespeare Association of America. How is the F2F experience of the seminar format reflected in how the essays in this volume “speak” to one another?

MJS: Exactly. Fourteen Shakespeare scholars gathered to discuss papers that consider “moments of copresence, such as intimacy, exchange, hospitality, dining, conversation, collective storytelling, touching, dance, and confession” on the Shakespearean stage. This may sound like a purposely uncurated list of normal human activities. But we tried to imagine these interpersonal activities outside of the abstract forms they take in institutions and in philosophical discussions and instead as moments of contact. People—and in this case, characters—look to, speak with, understand about, and turn toward others. Theater highlights such interpersonal stagings. As in the seminar, the essays in this volume emphasize the middle term of the face to face. The energy of their readings is predominantly second-personal, focused on scenes where characters call or turn toward another, or hide from another.

Julia, your own writing on hospitality, trust, and thinking “with” Shakespeare played a significant part in inspiring the seminar from which this volume grew. If you reflect on the essays in this collection, what do you think is most revelatory or unique about F2F interaction in Shakespearean drama?

JRL: I was observing rehearsals at our summer Shakespeare festival when we were working on the introduction. Larry Manley’s endlessly insightful essay on love duets in Shakespeare took me to Bernard Beckerman’s Theatrical Presentation. Beckerman shows how Shakespeare composes his scenes out of duets. The theater, however, demands that actors face outwards to the audience while speaking to each other. I became attentive to this tension between the face to face as the building block of conversation and the frontality required by the stage. In our volume, I am most excited about those moments when a feature native to performance — stage-fighting in Emily Shortslef’s piece, the introduction of the close-up into theater via video projection in W. B. Worthen’s essay, the appearance of trust games in Macbeth explored by Jennifer Waldron — yields unexpected philosophical returns.

We ended up subtitling the volume “Ethics, Performance, Philosophy.” Can you talk about the ethical stakes of the F2F?

MJS: The contributors tried to think about ethics not primarily through theme or genre, but through the technologies, materials, and movements of the stage. Determining exactly what this means—the moral deliverances of a character facing another, for instance—is the challenge that motivates this volume. Kevin Curran’s piece on judgment is a case in point. How, he asks, can we reverse engineer scenes of judgment such as those in Measure for Measure? Rather than simply assuming a rule of judgment that predetermines the end of conflict, Curran traces the physics and grammar of judgment in the movement and language of the scene. Judgment—sympathy, trust, and deception—is never simplified in theater. All the pieces argue against over-simplification. Hence the influence of philosophers like Stanley Cavell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Hannah Arendt throughout the volume.

Julia, Do you have any thoughts about the fate of F2F communication today?

JRL: I am working right now on developing an online Shakespeare class, and it presents real challenges to my pedagogy. So much happens in my classes when my students and I engage in F2F conversation. Yet I also want to expand access to Shakespeare for students who might not be able to take the F2F version because of jobs or other coursework. I also want to bring in guest lecturers and theater professionals, like this interview with choreographer Lar Lubovitch. It’s easier to develop guest appearances for an online class that will run for several years. When I am in front of the camera recording my lectures, I focus on being as present as possible and speaking to students as if they were in the room with me. I hope it works! I am also exploring multi-media projects, like selfie soliloquies (an idea I got from Joseph Campana at Rice University). I want students to interact with each other and also develop communications skills that might not be emphasized in a traditional English class.

Matt, you have a great piece in our volume about recognition scenes in Shakespeare. How does this fit into your next project?

MJS: Like your own experiments with multi-modal projects, what motivated my essay contribution on recognition in Cymbeline is the basic question of whether the face to face really does make a difference. And the history of this question is recorded in the modern philosophical history of “recognition,” in the work of writers like Hobbes, Kant, Hegel, Buber, Levinas, Ricoeur, and Cavell. I’m writing a book called “Shakespearean Recognitions: Philosophies of the Post-Tragic” where I ask whether the dramatic recognition scene has anything whatsoever to do with moral and social achievements of mutual recognition as it’s been theorized since Shakespeare. Does this ancient convention of theater—anagnorisis,the reunion—have the power to redefine one’s own freedom or even one’s spiritual condition? I’m charging into hallowed ground by arguing that in Shakespeare’s plays Aristotle indeed does meet modern continental philosophy, that the poetics of recognition does intersect with the politics of recognition—for better and for worse.

Julia, what message does Face to Face in Shakespearean Drama have for people participating, for instance, in a course on Shakespeare?

JRL: Drama is composed out of F2F interactions, and so is teaching (even when it happens online). Looking for moments of intimacy and care, listening and respect, attention and concern, in Shakespeare’s plays not only humanizes the classroom; it can also give us new tools for living.

Matthew J. Smith is Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Azusa Pacific University.

Julia Reinhard Lupton is Professor of English and Comparative Literature, as well as Associate Dean for Research at the School of Humanities, University of California, Irvine.

Face-to-Face in Shakespearean Drama: Ethics, Performance, Philosophy published in June 2019.