Earlier this year, the United States government declassified more than 40,000 documents showing the American intelligence community’s reporting on the Argentine dictatorship’s Dirty War. This refers to Argentines’ counterinsurgency campaign that decimated their country’s far left in the late 1970s. As The Guardian explained, this effort – essentially state-sponsored terrorism – was part of a transnational security and intelligence network called Condor, after Chile’s national bird, in deference to that nation’s anticommunist dictator, Gen. Augusto Pinochet, who contributed to its creation and direction.

Condor’s activities

Condor brought together military officers and covert operators in southern South America from Ecuador to Brazil and Argentina. To cite but three of its most dramatic actions, it was responsible for:

- Assassinating Chilean Gen. Carlos Prats and his wife Sofía in Buenos Aires by car bomb in September 1974.

- Shooting exiled Chilean Senator Bernardo Leighton in Rome in October 1975.

- Murdering former Allende administration official Orlando Letelier, also by car bomb, in Washington, DC in September 1976.

This was in addition to the extrajudicial arrest, detention, interrogation, disappearing, and/or killing of tens of thousands of others in Latin America that decade.

Transatlantic interest

Where the Phoenix Program had failed to neutralise the Vietcong insurgency’s infrastructure in South Vietnam (in the Apocalypse Now-style jargon of the time), Condor wiped out Argentina’s urban guerrillas and their counterparts in southern South America. This effectively ended the Cold War there by the end of the 1970s. As The Guardian pointed out, this attracted the interest of British, French and West German intelligence services. They dispatched officers to Buenos Aires to study Condor’s organisation, strategies and methods, particularly with respect to liaison and coordination, in September 1977. Why? They were considering setting up a comparable network in Europe.

Condor in context

From the perspective of multiarchival international Cold War history, the interest of these Western European intelligence services in Condor connects southern South America to a larger, transatlantic context. This matters because so much of the literature on Latin America’s Cold War remains narrowly confined to questions about the United States’ covert operations in the region, within an exclusively inter-American framework. In Chile, the CIA and the Cold War: A Transatlantic Perspective, I explore this transatlantic context. Among the key insights it offers to this still unfolding part of global intelligence history are:

Interest from the West

The British, French and West German intelligence officers who came to Buenos Aires in 1977 were merely the latest expression of European and Russian interest in southern South American political, military and intelligence affairs. This can be traced back to the British, French and Prussian missions that professionalised the region’s armed forces, beginning in 1880s. In the 1920s, the Comintern formed the South American Bureau, also located in Buenos Aires, which started to support proletarian revolution there and elsewhere in the world.

Interest in the West

The strategic thinking behind Condor first appeared when Chileans vigorously pressed the United States and others to sign on to something comparable to it at the Organization of American States’ (OAS) charter meeting in Bogotá in April 1948. Chilean President Gabriel González Videla’s linked his administration’s difficulties with the Chilean Communist Party to his counterparts’ problems with communist parties in Belgium, France, and Italy – and to the Czechoslovakian coup, which particularly outraged him. So there was a reciprocal interest from southern South American in European political, military and intelligence affairs. All shared the same perception that they and their politics and history occurred within an overarching transatlantic space, not merely a western-hemispheric one.

Model cold warriors

Ground conditions – particularly southern South American politics, decisions and activities – were far more important to the region’s Cold War history than external or internal interventions. Indeed, as the assassinations, attempts and other extra-regional interventions illustrate, Chileans, Argentines, Brazilians and other southern South Americans were enthusiastic, fully engaged cold warriors. They defined and implemented their own agendas in such a way that made other cold warriors across the world want to learn from them.

By James Lockhart

James Lockhart is assistant professor of history at the American University in Dubai. He was born and raised in the American Southwest. He studies American foreign relations, security, and intelligence, specializing in US-Latin American relations, particularly southern South America during the Cold War. He earned a PhD in history from the University of Arizona. James likes to travel, watch films, listen to live music, snorkel and chat with students when not researching and writing history.

Image credits

- ‘Condor In Isla Riesco’ by Pablo Vezzani, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

- ‘Condor pearched – panoramio’ by awswimmer, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

- ‘Carlos Prats González’ by Portada Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0 CL)

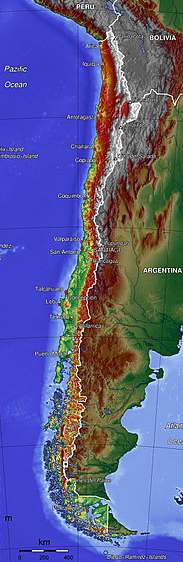

- ‘Chile topo en’ via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Your blog is an educational treasure. The detailed research and engaging storytelling in each post make learning about World War history an absolute pleasure. I appreciate the effort you put into making history accessible and interesting for your readers. Thank you for your dedication.