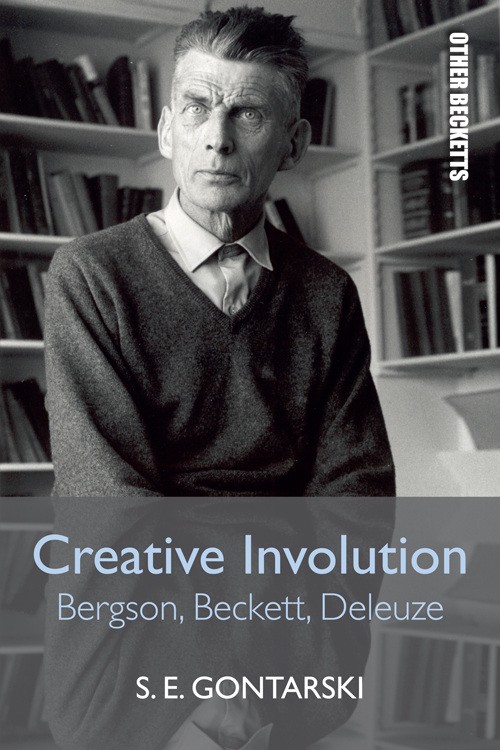

Professor Stanley Gontarski in Conversation with Jacek Gutorow regarding Creative Involution: Bergson, Beckett, Deleuze, the first book to publish in the Other Beckett series.

At the center of the book we have Beckett and Bergson. As to the latter, we need perhaps a little clarification and explanation. All the more because Beckett is traditionally associated with the tradition going back to Descartes and post-Cartesian thinkers (most notably Arnold Geulinxc) or Berkeley. What do we achieve by stressing the importance of the Bergsonian moment in Modernism in general, and Beckett in particular? Does this context help us find a new perspective on SB?

Well, it is the function of the book to explain how Bergsonian and Deleuzian perspectives opens and clarifies issues in Beckett’s texts, and such an answer is what the Interiors section was designed to do. Much has been written about Beckett and the other philosophers you mention to the point that those touchstones have become ossified, the received wisdom, the repetition of those associations adding nothing new to our understanding of how Beckett’s texts work, and this is the key, how they work not what they might mean. My arguments tries to show how Bergsonism, which Beckett references some, opens up the text of “Watt,” in particular, the way no other philosophical perspective has heretofore, and how many of Beckett’s texts deviate from traditional aesthetic issues of representation. Descartes, Berkeley, etc., help us only little to understand this anti-representational quality to Beckett’s work, and I take this resistance to representation, and finally the impossibility to get beyond representation once one is committed to language, to be the core of Beckett’s innovation and an explanation of why all art must fail.

With Bergson, we usually come up with the notion of creative evolution. You stress the significance of the creative involution. Could you explain how you use the term? Can we (and how) apply it to Beckett’s oeuvre?

Well, the traditional views of evolution have to do with species in response to their environments, which is an external, material cause and effect. Bergson takes issue with that model since it cannot account for much in human development. Deleuze picks up the thread of Bergson’s argument and describes a turning inward of volution a both neo-evolution or involution, the latter without the usual medical connotation of diminishment. Quite the opposite. It is why as well the central portion of the book is called Interiors.

In many places you refer to Bergson’s critique of the concept of nothingness. I find it a very interesting moment as Beckett is very often described as an advocate of nihilism. This is for example how Czeslaw Milosz addressed SB: as a literal nihilist. So Bergson is I think quite helpful here because his objections to the idea of nothingness might be used as arguments directed against the vision of Beckett’s work as nihilistic. Shall we defend SB against the charge of nihilism?

Yes, and your analysis gets to the heart of the matter. That nothingness, which we see in Beckett not as emptiness, but the fullness of potential and possibility that Deleuze will call virtual; this is the best argument I know against the charge of Beckett as a nihilist. On the contrary (as Beckett said of his Englishness), I would argue that Beckett is constantly opening up new worlds and so new, fresh possibilities.

In the book you write a lot about the problematic nature of identity, introducing the Deleuzian concept of multiplicity. Also, you touch upon the question of the vanishing author, another poststructuralist argument. Could you develop these ideas here?

Deleuze actually borrows the term “multiplicity” from Bergson and so that is a powerful connection between the two metaphysicians, and Beckett has been interested in the breakdown of singular discrete entities, including the idea of being, which I argue is always multiple in Beckett, and which multiplicity Beckett finds early on in Heraclitus. In fact my workshop on “Ohio Impromptu” is designed to foreground multiplicity in Beckett. As for disappearance, Beckett has been talking about the vanishing author since his earliest discussions of “Godot.” I end the book, taking a cue from Deleuze and Beckett’s one and only film, which we will discuss later in this conference, as the pursuit of invisibility, perhaps a synonym for non-being, Murphy’s goal too, perhaps.

How about Deleuze (and Guattari)? As you have noticed, Beckett probably never read the philosopher. How do you interpret SB through Deleuze? What interesting conclusions have you arrived at?

Again, this may be for the reader of the book to decide, what “interesting conclusions” are arrived at, but generally what I focus on is Beckett’s characters’ inability to accept existence for what is it, a series of shifting, groundless exchanges, each of which opens new possibilities, which many of Beckett’s characters, Watt in particular, cannot accept.

At one moment you refer to something you call the Museum of Modernism. In this perspective the modernist text (be it a poem, a novel or a stage performance) is self-contained, complete in itself and doesn’t allow any changes. We know that one part of Beckett revered such a vision of literature – he didn’t accept reinterpretations of his works, even at the cost of intelligibility, and he always advised both actors and directors to keep to the letter of the text. With Bergsonian credences, you prefer to look at Beckett’s art as flexible and living, undergoing constant reformulations and re-imaginings. Do you think SB would accept such a stance? And how free do you feel in your own adaptations of his plays? Do you think there is a limit to this freedom?

The issue of adherence to Beckett’s texts is one of whose vision we are presenting, Beckett’s of the views of additional parties, directors, actors, scene designers. It is possible to loose or limit Beckett with too much emphasis on reinterpretations. But such reinterpretations also show the range and flexibility of Beckett’s work. Both approaches are valid and useful so long as we underscore their differences. As for a rigid text, Beckett had radically reshaped and rewritten his texts every time he has turned his attention to them either as translator or theatre director. Such mutability I call, after Bergson, process, which should not be stilled if the works are to remain a living part of contemporary culture. Rigid adherence can lead to demonstration pieces and thus wind up in the Museum of Modernism.

You situate Bergson and Beckett in the modernist context. However, both the Deleuzian interpretation and the important (I think) reference to William Burroughs in the last chapter of your book seem to suggest that after all you go beyond modernism. This impression is particularly strong when we read the essay devoted to Burroughs. However, we know that SB was pretty much reserved about Burroughs and he was not interested in the French post-structuralist philosophy. So, are we entitled to interpret Beckett as post-modern? Or should we rather stick to Anthony Cronin’s description of SB as the “last modernist”?

This may be a semantic issue since Beckett’s roots are in and he is thus strongly associated with the Modernist ethos, and this association is the topic of my plenary lecture at this conference, by the way. How much Beckett stretched Modernist assumptions, aesthetics, and ideologies is what is at issue. There may be a point where differences of degree become differences of kind. I find it most useful to see Beckett as a late modernist, as is Burroughs, I might argue, but neither necessarily “The Last Modernist,” which is a catchy title, but cuts off the process of continual modernist reinvention. I have a book scheduled for publication in November entitled “Beckett Matters: Essays on Beckett’s Late Modernism.” Furthermore, I think the term “post-modern,” like “absurd, has outlived its usefulness.

My favorite passage in the book is on page 67. Let me quote it: “Beckett’s readers (should) enter his texts, for they are best read from the inside, the reader part of the process rather than apart from it.” This reads almost like a critical and readerly program. Could you please elaborate on it?

Well, on one level, this is straight Bergson. Check the opening to “An Introduction to Metaphysics.” Second, this is the nature of “Creative Involution.” Third, such an involutionary perspective gets us away from constantly approaching Beckett’s work as a second order of reality, as a simulacrum of our own world.

S. E. Gontarski is Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of English at Florida State University, Ph.D., Ohio State (1974) and specializes in twentieth-century Irish Studies, in British, U.S., and European Modernism, and in performance theory. Creative Involution published in 2015 with Edinburgh University Press.