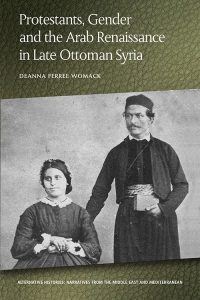

Events such as the Arab Spring and the civil war in Syria have brought Middle Eastern Christians into the public eye in Europe and North America. Yet the academic field of World Christianity still gives little attention to the Middle East. My new book – Protestants, Gender and the Arab Renaissance in Late Ottoman Syria – helps fill this gap, but further work could be done. Here are some reasons why more studies on global Christianity should include the Middle East…

1) The Holy Land is a focal point for Christians around the world but is also home to contemporary Christians.

Throughout the history of Christianity, Jerusalem has been the center of pilgrimage (and tourism) for travelers of multiple denominations from across the globe. Many who journey there are dazzled by the city’s holy sites, but they often overlook the Christians still living in the region. Scholars should not be similarly blinded to the realities on the ground. Christianity in the Middle East is not ancient history. It is a living faith with vastly diverse church traditions. In Lebanon alone, twelve of the eighteen officially recognized religious groups are Christian: Armenian Catholic, Armenian Orthodox, Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic, Coptic Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Maronite Catholic, Greek Catholic (Melkite), Protestant, Syriac Catholic, and Syriac Orthodox.

Right: Pilgrims at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, shared by Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Coptic, Syriac Orthodox and Ethiopian Orthodox churches.

2) Modern Middle Eastern Christianity is global.

Since the nineteenth century, migration has made these diverse Middle Eastern Christian communities truly global. As early as 1924, scholar Phillip Hitti identified more than 100 churches in North America established by Christian immigrants from Ottoman Syria (modern Lebanon and Syria). By that time, Christian Syrians had settled in Europe, North Africa, Central and South America, and Australia too. Due to such migration trends, millions of Brazilians today have Lebanese ancestry (most of them Christian). Some even claim that there are more Lebanese in Brazil than in the republic of Lebanon (but that depends on how one defines Lebanese identity).

3) Transnationalism has shaped Middle Eastern Christian identity.

Christians from the Middle East did not just settle around the globe. They also moved back and forth between their homeland and other nations. To take one example from my research, in the early 1900s a Syrian Protestant named Salma Badr migrated from Beirut to Melbourne, Australia. Then she returned to Syria to work for British missionaries, and finally she relocated again to New York City and married another Christian immigrant from Egypt. Such migrants also exchanged goods and information across transnational networks. Khalil Sarkis and Luisa Bustani Sarkis, a prominent Protestant couple in Beirut, received hundreds of condolence messages from Christian Syrians abroad following the deaths of four family members around the turn of the century. Friends and relatives sent them letters, telegrams, poems, and newspaper obituaries from Pennsylvania, New York, St. Louis, San Juan Bautista (Mexico), London, Paris, Cairo, Alexandria, Constantinople, Aleppo, and Damascus, among other locations.

4) Early Middle Eastern Christianity migrated too, and those traditions continue to thrive in places like India.

Middle Eastern migration is not just a modern phenomenon. In the early centuries of Christianity, distinct Middle Eastern traditions spread across oceans and continents. The ancient Syrian churches in India are one reminder of this movement. Syrian Christians there are known also as Saint Thomas Christians because they trace their origins to St. Thomas the Apostle, whose tomb in Chennai is an important pilgrimage site. Persian crosses on churches throughout the south Indian state of Kerala reflect the later missionary efforts of the Church of the East. These deep connections to Syriac Christianity continued into the modern period as bishops from Mesopotamia served churches in India. Indeed, such ties remain strong today, particularly in Kerala, where a number of different denominations follow the Syriac liturgy (in Syriac or the vernacular Malayalam) and still respect the authority of Middle Eastern bishops.

Right: St. Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church altar (known as Kottayam Cheriapally), established in 1579 in Kottayam in the Indian state of Kerala.

5) The global church is present today in the Middle East.

Along with many Christian expatriates from Europe and the US, today millions of Christians from the global south reside in the Middle East. Some have fled war and violence, like the congregation of Sudanese refugees who worship at All Saints Cathedral in Cairo. Others are migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia, who are a significant part of the Christian population in the Gulf states. In Beirut, Protestants from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe form the International Community Church, a sister congregation of the first historical Arab Protestant church, the National Evangelical Church of Beirut.

Deanna Ferree Womack is Assistant Professor of History of Religions and Multifaith Relations at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology and director of the Leadership and Multifaith Program (LAMP) in Atlanta. Ordained in the Presbyterian Church (USA), Womack has lectured and published widely on the subjects of Arab Protestantism, mission history, world Christianity and Christian-Muslim relations.

Protestants, Gender and the Arab Renaissance in Late Ottoman Syria by Deanna Ferree Womack is available now in the Alternative Histories series. Visit the Edinburgh University Press website to find out more