Written by Stephen Bamforth

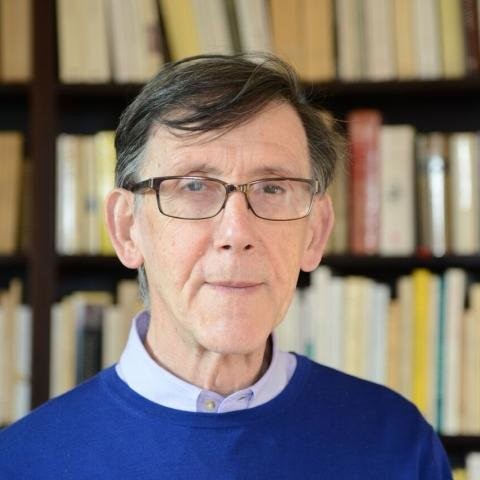

Michel Jeanneret was a great friend of Nottingham French Studies, and we were greatly saddened by the news of his death on 3 March this year. Michel was our Special Professor in the Department of French at Nottingham from 2006 to 2009, and the Autumn issue of the journal in 2010 takes the form of a volume of studies in his honour, intended both to celebrate Michel’s international reputation as a scholar and to mark our own happy association with him during his three years with us.

Michel Jeanneret

I was the editor of that volume, and it seems entirely fitting both to me, to the current editor of the journal and to the Editorial Board as a whole that we now make that special number freely available via the EUP website. Our thanks go to EUP for making this possible.

My own introduction to the volume speaks already of Michel’s breadth of interests and his stature in the field of French Studies. The essays that the volume contains had their beginnings in a one-day colloquium held in May 2009 that was itself inspired by Michel, intended to show the richness and diversity of early modern studies and the new directions they were taking. Because of that, an essay by Michel himself opens the collection, and its title now seems particularly apt. La vie et l’œuvre seems to be the right tag for Michel himself. His was a career selflessly devoted not just to a consistently insightful and original scholarship, but also and perhaps above all to his students and his colleagues in all the different institutions in which he worked, whether from Geneva to Johns Hopkins or from Nottingham to Beijing.

Our own students certainly benefitted from his all-too-brief residencies in the department. He was unfailingly generous and open with his time, always ready to answer a question and engage. Exactly the same approach of course characterised everything that he did. Michel was never a grandstanding scholar, but on the contrary ever open to dialogue, unassuming and courteous in his exchanges with others. Michel’s manner sat alongside a penetrating and rigorous scholarship, which examined everything it was directed to with originality and freshness of approach.

The title of the colloquium on which this volume was based was ‘nouveaux objets et nouvelles perspectives des études seiziémistes’. Shortened for publication, this became ‘nouveaux départs’. Nothing could express more eloquently what Michel’s many books and articles consistently represented. Each, in its own way, broke new ground. There is no need here to recite the list of his many publications, but they were all marked by the same lucidity, elegance and above all incitement to make the reader think. In the article which Michel wrote for us here, he refers to the work of the French philosopher and historian of philosophy Pierre Hadot, and to the way in which Hadot evoked the philosophy of the Ancients as less a theory than a praxis, an ethics indissociable from a mode of life, and one which is moreover rooted in a sense of community. ‘Non pas informer, mais former et transformer’ is the phrase which Michel uses. It is a phrase which informs – to continue in the theme of Michel’s own fascination with words – his own work as well. We are proud at Nottingham to have been associated with that endeavour ourselves.