By Marc Abramiuk, archaeologist and applied anthropologist

The central Helmand Valley of Afghanistan is the name I use to describe the section of the Helmand River basin lying between the confluence of the Arghandab and Middle Helmand in the north, and the dramatic bend in the Helmand River’s course in the south. The valley’s rather narrow green zone and stark sandscape, which bleeds into the green zone, belie not just the substantial agricultural potential of the region, but the cultural richness that the region has fostered. This latter observation has been further obfuscated unfortunately by forty years of war that have taken a toll on lives and peoples’ morale in the region.

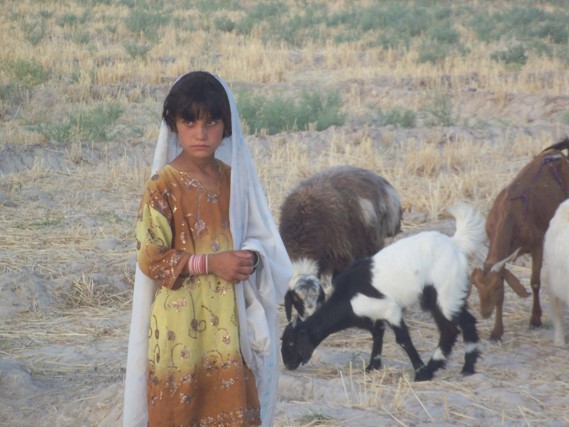

In 2011 when I worked in Helmand Province, I often found solace in observing the cultural diversity of the region. I recall how striking the nomadic Kuchis (of Baloch and Pashtun stock) were in their adherence to a cyclical migratory pattern which has persisted despite the ongoing war that threatens their way of life. A perfect example of what anthropologists refer to as transhumance, the Kuchis would migrate to the foothills of the Hindu Kush in the summer and would return to the central Helmand Valley in the winter. The persistence of this cycle, which has likely changed little over the generations, was remarkably heartening to me in its suggestion that there were forces at work that are greater, more powerful than war.

I also observed how the Pashtuns in the villages lived. Their land tenure system continues to form the basis for political leadership, just as it did in 1959 as described by Frederik Barth. Although Barth conducted his fieldwork in a very different area than I had, the similarity in the way that both groups of Pashtuns/Pathans had organized themselves is quite telling. The land tenure system, which I had the opportunity to observe, maintained “feudal” overtones that were likely vestiges from much earlier times. To me, it offered a glimpse into how village life would have unfolded in the past, which to an archaeologist is the next best thing to being transported into the past.

The ongoing war has certainly affected people in the central Helmand Valley in ways that will not be described here. However, what has not been affected significantly are the ways that people in the region have systematized themselves. Perhaps it is the tether to the environment that has made each of these systematized ways of life so resistant to incursions. Whatever the case, I look back at my time in the central Helmand Valley in wonder. As an archaeologist, I can’t help but foresee that the ways of life that I observed will carry on long after the war has ended. As an applied anthropologist, I can’t help but believe that the key to overcoming adversity caused by the conflict lies in better understanding these ways of life that have existed for centuries if not millennia.

Marc A. Abramiuk, Ph.D., RPA is an archaeologist and applied anthropologist.

Having worked in development, defense, and education, his research products range from purely scholarly to applied. His primary research interests in human cognitive evolution and the dynamics of civilizations has compelled him to cross into the domains of ethnography and ethnobotany, as well as archaeology. In the course of his career he has led and supervised archaeological and applied anthropological projects in some of the more logistically challenging parts of Central America and Central Asia. He is currently a lecturer at California State University Channel Islands and works as consultant.

His article is published in Afghanistan, Issue 2.1