Where did this excitement come from?

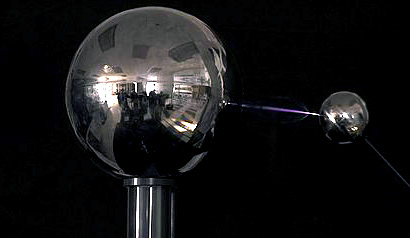

Francis Hawksbee the Elder built his influence machine and people experimented with rubbing glass balls and rods of resin. And then, during the 1740s, the phenomenon of electricity became a subject of popular wonder in the salons of Europe, especially in Germany. Fascinated by Hawksbee’s experiments and Dufay’s writings, Georg Mathias Bose, a young poet and physicist from Leipzig, devised a series of technical feats intended to impress a public of respectable ladies and gentlemen who hurried to admire the spectacle of this new fire, ‘electric fluid’, surging spontaneously from matter.

‘Sanctified by science and frozen with surprise’

What did Bose’s device consist of? He would invite guests to break bread with him. Beforehand, he would insulate all the furniture and his own chair. The apprentice wizard would then discreetly touch a thin copper wire placed under a tray and connected to a hidden generator activated by an accomplice; then, with gravitas, Bose would put his hand flat on the table. The current passed along the guests’ arms, which they would politely rest on this same table, and the crowd, sharing a look of panic, would become overjoyed, surprised, and dishevelled, their hair standing on end as it teemed with thousands of crackling sparks. ‘It’s marvellous!’ one exclaimed. A few months later, Bose invented a machine for mechanical beatification, with the ‘saint’ seated on an insulated chair, the top of his head covered by a little pointy metal hat, under a sort of crown of bits of cardboard and junk. The current was diffused by a long wire that hung just above a metal plate. Situated barely a centimetre higher than the crown, it set off a crackling of sparks that outlined a halo above the head of the person now sanctified by science and frozen with surprise.

‘My mouth twisted, and my teeth almost broke!’

Bose’s imagination was particularly drawn to an attraction called ‘the electric kiss of Leipzig’, which he lyrically describes in his poem ‘Venus electrificata’. Having been insulated from the current beforehand, a beautiful young woman would be connected to Bose’s primary generator, her lips coated with a conductive substance. An honourable audience member was then invited to come up and kiss the girl. The twenty-something-year-old man would bring his quivering lips close to those of the Venus and suffer a violent discharge. The astonished public would then see a surging flash between the mouths of the two young people. The man, having literally received the shock of his life, would be momentarily dazed, the power of the electricity, the fire emanating from the woman, leaving him breathless. ‘The pain came from up close, and my lips were quaking. My mouth twisted, and my teeth almost broke!’

‘A fire of the purest kind’

Bose, the maths professor Hausen, and Winkler, their young colleague in Eastern languages, all set Leipzig ablaze with audacious experiments straddling the line between physics and quackery; in this period, the ‘electric fairy’ (la fée électricité) was still a magical form of scientific entertainment, an irrational promise of reason. Soon enough, the games would be replaced by theories. But, for the time being, the fumes of this subtle fluid sparking a fire in the ether stoked the spirits of Europe and sketched the outline of a new image of human desire. ‘Madame, you are now filled with fire, a fire of the purest kind, one that will cause you no pain as long as you keep it in your heart, but one which will also make you suffer as soon as you communicate it to others.’ Lying latent, perhaps this internal fire is to blame for only revealing itself through contact with her suitor, the man who tries to kiss her. This fire represents the desirability of the young woman; sensual desire is like an electric force and, conversely, electricity is like the natural libido of all matter, just waiting for its suitor, humanity, to reveal itself.

‘The shiver of a new intensity’

In the guise of desire, electricity is not without danger, but it triggers the shiver of a new intensity, that of an ‘unthinkable fluid’. We still did not know the nature of this fluid or its possible uses. The human body served as the principal conductor for these first demonstrations of electrostatic power. Like an electric shiver through the body, something happens that makes manifest the occult power of certain objects to repel or attract others, to heat up, to set off sparks, and to produce a combined discharge of energy and light. But soon the human body was replaced by metal. Flesh, muscles, and nerves were separated from this mysterious impulse. It returned to its place within things, as the first electrostatic generators, Leyden jars, batteries in cylinders, and trays of thousands of jars were constructed.

‘An intoxication cultivated by the modern mind’

But then electricity entered into humanity, where it would always remain as a sort of intoxication cultivated by the modern mind. Like blood coursing through the veins of society, electric light spread through optical science and transported fabulous cinematographic images to the screen. It broke the image into a thousand bits of light, decomposed and encoded it into short pulses capable of being transmitted over distances, and made way for the diffusion of television. It invaded all data, images, texts, and sounds and then placed itself in the service of electronics. It illuminated the street lights of the great capitals as well as the lamps above the beds of children reading late into the night. It fed the indefatigable motor of growth and progress. It demanded that dams, generators, power plants, and windmills be constructed. It set in motion all things or nearly all things to the extent that humanity, without even knowing it, became the living medium between entities (cables, telephones, radios, pacemakers…). Little by little, humanity forgot the electric nature of those entities, but the idea remained in the bloodstream. It was as if Leipzig’s kiss, which sealed the modern alliance of desire and electricity, had never ended.

Find out more about The Life Intense on the Edinburgh University Press website

About the Author

Tristan Garcia is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Lyon III and an award-winning novelist. He is the author of Forme et objet. Un traité des choses (PUF, 2011), translated into English as Form and Object: A Treatise on Things (Edinburgh University Press, 2014). His other philosophical works include L’Image and Nous. His fictional works include Les cordelettes de Browser, En l’absence de classement final and Mémoires de la jungle. In 2008, he received the Prix de Flore for La meilleure part des hommes, translated into English as Hate: A Romance.

Image Credits

Detail from ‘Blue Body of Water With Orange Thunder’, Johannes Plenio, CC0, via Pexels

‘Georg Matthias Bose’, Unknown author, Die Angewandte [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

‘Van de graaff generator’, Littlebet12 [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

‘1877 Aphengoscope’, A.E. Dolbear [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons