An interview with Corey Kai Nelson Schultz

What inspired you to research this area?

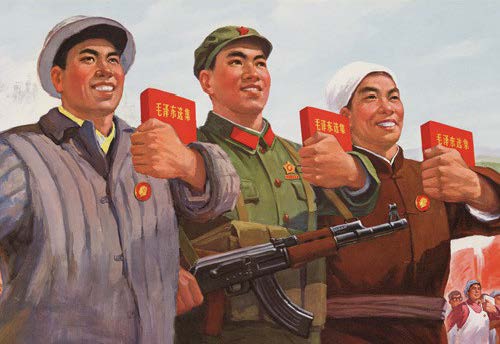

In 2008, I saw Jia Zhangke’s film Still Life, and it changed my life. I had never seen a film that had affected me so intensely and knew that, after that moment, I needed to research this director and his films further. What impacted me the most about Jia’s films were their emotional and affective qualities, and how they evoked feelings that lingered long after the films had ended. Wanting to examine these feelings further led me to theories on film phenomenology and affect, as well as Raymond Williams’s notion of “structures of feelings” – feelings that concretise around a particular time and place that are captured and evoked in art and culture. During my viewing, I also noticed how specific class figures were omnipresent in the films, such as the Maoist class figures of “worker, peasant, soldier,” as well as the “intellectual” and the “entrepreneur,” and thus chose these figures as the book’s structure. I discovered that these figures had affective power not only through their representation (connecting to their historical use in Chinese visual culture), but also through specific cinematographic tropes that were associated with them.

Tell us more about the class figures in Jia’s films?

The Worker

The figure of the worker was created in the Maoist period to develop the nation, but now, in the modern-day Reform era, a period that began in 1978/79 in which the state transitioned to a market economy, they are associated with imagery of ruin. They are thus no longer the “builders” of the Socialist nation, but live in its ruins. I focus on Jia’s film 24 City, which is dedicated to this group, arguing that it commemorates and elegizes the worker through its use of interviews and long-take “moving portraits” (which I also call “portraits in performance”).

The Peasant

The figure of the peasant has an ancient history in China. In the films, this figure is represented as elderly and ready to expire, while their descendants have become migrant workers (mingong) who are the modern day precariat that wander the nation in search of employment to support bare existence. I examine two cinematic forms associated with the peasant – the point-of-view (POV) shot and the observational shot, arguing that the POV evokes empathy whilst the observational shot evokes sympathy, and the difference that this entails. I finish by examining the mingong gaze in some of his films, which silently demands acknowledgment of their current state.

The Soldier

The soldier was associated with honour, bravery, and protection during the Maoist era, but often “appears” as simulacra in the films as police officers, security guards, and entertainers dressed as soldiers. These representations become increasing degraded during the course of the films, thus emphasising the loss of these previous Maoist qualities. I conclude by examining the soldier-like wuxia (martial arts) hero in A Touch of Sin, arguing that he is a vengeful figure that symbolizes the immediate need to address increasing social and economic disparity.

The Intellectual

The intellectual appears primarily in Jia’s documentaries Dong and Useless, and is associated with patriotism, altruism, and the desire to “save” the nation and its people. In these films, I examine the voice – the power of the voice, the class that has it, and its effects. I also examine the “voice” of the camera (which I interpret as the voice of Jia Zhangke), and how it changes from passive observation to more active exploration. Regarding this figure, I argue that the voice of the intellectuals “Others” the masses for whom they’ve assumed a moral obligation to speak, thus emphasizing the group’s moral power.

The Entrepreneur

Finally, the entrepreneur figure appears in many of Jia’s films as a threatening figure that represents and evokes the anxiety surrounding market reforms. However, some of the films also feature the figure of the rushang – a businessperson who is depicted as philosophical, friendly, and inspirational, and is tempered by traditional Confucian values such as filial piety, patriotism, and anti-materialism, thus making it a figure to be lauded, not feared. Such people have adapted to the new economy and are thriving because of it, but remain altruistic towards the masses and thus serve as inspirational models. I conclude by arguing that this is a new figure for emulation for the contemporary Reform era.

- Find out more about Moving Figures: Class and Feeling in the Films of Jia Zhangke on the Edinburgh University Press website

- Browse all books in the Edinburgh Studies in East Asian Film series

Corey Kai Nelson Schultz is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Film at the University of Southampton. He received his PhD from Goldsmiths, University of London, and his research areas are Chinese visual culture, film phenomenology and aesthetics. He has published in Asian Cinema, Film-Philosophy, Moving Image Review and Art Journal, Screen and Visual Communication.