What’s the artist for in modern Scotland? Curating our accumulated history? Envisioning our possible and impossible futures? Diagnosing the ills of our present and prescribing treatment for the body politic? Showing us who we are, or who we ought to be?

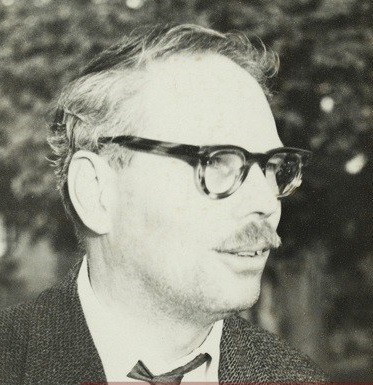

My study of Hamish Henderson (1919-2002) and his vision of cultural politics describes a lifelong struggle with these big questions. Celebrated as a folk-hero, war-poet, political activist, songwriter and folklorist, Henderson has been a repository for many often-conflicting ideas about Scotland’s sense of itself. His memory has been invoked repeatedly in recent years, as radical constitutional resettlement is reimagined. In this particular historical moment, I think Henderson can help us to think through some vital challenges. For example, how can our art, and our cultural diet, help advance social justice and enshrine a new collective politics? If we’re going to build something humane out of the ruins of neoliberalism in the early twenty-first century, can it be informed by the oldest surviving parts of our cultural inheritance, by our folk culture? Can it be informed by romantic, volkish notions of the ‘nation’, and somehow still be socialist and internationalist? And what is the role of the artist in all of this? Patronising poet-visionary, who can see further down the road than a helplessly blinkered readership? Or, passionate advocate for the people’s own creative voice, looking to dissolve in an immense anonymous tide that will, one day, find its radical application of its own accord?

The Voice of the People: Hamish Henderson and Scottish Cultural Politics (2015) looks to resituate Henderson as a major theorist of cultural politics in Scotland, emphasising his role as the first to translate the great Italian Marxist, Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) into English, as much as the larger-than-life figure he cut in clubs, lecture halls, and pubs during the high-tide of the post-war folk revival. It looks to his political philosophy as informed by the anti-fascist struggle before and during WWII, as well as his ‘discovery’ and promotion of Jeannie Robertson (1908-1975), ‘the world’s greatest folksinger’. And it takes his ‘flytings’ with the great nationalist-communist poet Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978) to be a self-conscious performance of some of the most vital debates of the mid-twentieth-century: that between mass culture and the avant-garde; between political vanguardism and collective, social-democratic advancement.

Henderson envisaged the role of the artist in society as one caught between an absolute submission to the collective tide of human experience and the need to absorb and recreate this collective force according to an individual or personal credo. And he sought, relentlessly, to overcome this tension. He proposed to reconcile the self-conscious directives of political theorists, poets and cultural commentators of all kinds, with the unchecked, transcendent processes of the oral folk tradition. I think he thought that, in doing that, he would be practicing the kind of humility that is required of a folklorist, whilst also living up to his radical idealism, his need to do something for the cause of human emancipation.

His song, ‘The Freedom Come-All-Ye’, is often touted as an alternative national anthem; though it’s message doesn’t cohere with the jingoist flavour that seems to me to be a trope, if not a prerequisite. It envisages a Scotland that has fully acknowledged its bloody history of colonial criminality and seeks to exorcise it, not by erasure, but by radical democratic empowerment. It imagines a Scotland (and a world, for that matter) that has arrived at racial harmony, nuclear disarmament, post-scarcity socialism, and vast horizons of hopefulness. And yet, it’s all tempered and qualified by the melody, from ‘The Bloody Fields of Flanders’, and by the opening lines, which put this utopian ideal just out of reach, in the future, in the wind.

Corey Gibson is Assistant Professor of Modern English Literature at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. At the time of writing he is also a Research Fellow at the Harrison Institute, the University of Virginia.

The Voice of the People: Hamish Henderson and Scottish Cultural Politics (EUP 2015), is based on research which was awarded the G. Ross Roy Medal in 2012. It was shortlisted for the Saltire Research Book of Year Award in 2015, and it is now available in paperback. Find out more about The Voice of the People on the Edinburgh University Press website.