By Rod Rosenquist and Alice Wood

As we near the end of 2016, ‘the people’ keep finding ways to make political headlines. In Britain, a failed coup in a major political party has cleared the way for ‘the people’ to increase the mandate for a popular leader, while a referendum on the nation’s membership of the European Union roused ‘the people’ to vote ‘Leave’ in defiance of conventional wisdom – as some narratives would have it. In the wake of the vote for Brexit, Nigel Farage celebrated a ‘victory for real people’ – thus relegating the 48% who voted ‘Remain’ as neither ‘the people’ nor entirely ‘real’. They were ‘the elite’, the out of touch. In the US, even Donald Trump – embattled and denounced from all sides, including by his own party – still claims to speak for ‘the people’. In May, The Guardian reported that Trump responded to patchy support for himself by announcing that ‘the only important thing is the unification of the people – because the other people don’t mean anything’, in one tidy phrase uniting and dividing ‘the people’ into a public that counts and a public that does not. While celebrity politicians like Trump, Farage and Corbyn, or celebrated catch phrases like Brexit, continue to command attention, it is the public supporting them, antagonising them, or being imagined by them that makes this one of the more complex political decades in recent memory.

A hundred years ago, modernist artists and thinkers were negotiating many of the same tensions. Rising literacy, an explosion in print media and the development of new technologies such as broadcast radio and cinema led to a battle between cultural elites and the masses, in which modernist writers and artists sought to engage or reject the will and whims of this vast and indistinct general public. In recent decades, the perception of a ‘Great Divide’ between modernism and mass culture has been challenged by a number of critical works reviewing the relationship of the modernist artist to commercial markets, popular culture, the public sphere and the masses more generally defined. But in all this revision, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: modernism remains the subject of this critical narrative and ‘the public’ has remained its object. While the New Modernist Studies has exposed the endeavours of modernist artists to bridge this divide and the emergence of modernism’s ‘public face’, ‘the public’ itself continues to be seen, often through modernist eyes, as an homogenised mass – like Wyndham Lewis’s ‘The Crowd’ – there only for the artist to channel, to herd, to experiment with.

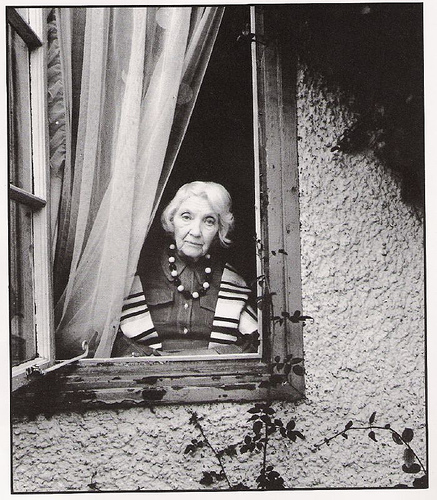

In a special issue of Modernist Cultures entitled ‘Modernism in Public’ (November 2016), we introduce seven articles on the two-way relationship between modernism and its various publics. We aim to show how far modernism was sometimes the object of mass culture – shaped, adopted, manipulated or outright rejected, openly and in public.For example, Sophie Oliver reveals how Jean Rhys’s modernist stories not only take fashion and the fashionable as their subject matter, but how, later in life, Rhys herself was made an object in mass-market periodicals, dressed up for photo shoots and framed by the renewed interest in her work. Rod Rosenquist traces the mirrored interests of Gertrude Stein studying advertising culture, and advertising copywriters studying her prose experiments. Faye Hammill explores the parties, and the glossy pages of gossipy magazines, where famous modernists, like Rebecca West, rubbed shoulders with celebrity non-modernists, like Noël Coward – at once heightening their position as cultural elites while allowing the public to join them backstage.

Alice Wood exposes the mutually-beneficial exchanges between modernists and the British edition of Harper’s Bazaar as this elite fashion magazine exploited modernism’s high cultural value to support its construction of a culturally sophisticated readership. Hana Leaper documents the attempts of Claude Flight and the Grosvenor School of artists to create a mainstream audience for their modernist linocuts, and Flight’s failure to understand the public whose taste he sought to influence. Daniel Moore surveys the efforts of British modernist artists and architects to cultivate public taste and effect widespread social change through design and decoration of the home. Finally, Andrew Thacker examines the bookshop as a commercial outlet for modernism and a cultural inlet for the public, a social space bringing together writers, readers and vendors of modernism within the shared language of being ‘We Moderns’. These enquiries into ‘Modernism in Public’ share the desire to uncover both how modernists approached the masses and how different versions of the public consumed, constructed or ignored modernism. Indeed, this special issue argues that ‘the public face of modernism’ should be understood not only as the face prepared by modernists to meet their public, but as the face offered to modernism by mainstream media and the public itself.

About the authors

Rod Rosenquist is Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Northampton. He is author of Modernism, the Market and the Institution of the New (Cambridge 2009), co-editor with John Attridge of Incredible Modernism: Literature, Trust and Deception (Ashgate 2013), and author of articles on literary celebrity and modernist life writing appearing in Comparative American Literature, Literature Compass, Critical Survey and Genre.

Alice Wood is Senior Lecturer in English at De Montfort University. She is the author of Virginia Woolf’s Late Cultural Criticism (Bloomsbury, 2013) and several articles exploring interactions between modernist writers and commercial periodicals, including a chapter on ‘Modernism and the Middlebrow in British Women’s Magazines, 1916-1930’ in Middlebrow and Gender, 1880-1945, ed. Christoph Ehland and Cornelia Wächter (Rodopi Brill, 2016).

I loved this reading.