By Deanna Ferree Womack

Images of Islam abound these days, and many of them are troubling. Those who speak loudly and most forcefully define Islam in the narrowest of terms, making one image – the militant extremist – into a type for all Muslims. I find striking similarities between recent American public discourses and Protestant missionaries’ portrayals of Muslims in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From a comparative historical perspective, it is clear that the oft-repeated tropes about Islam as a violent and oppressive religion have been transmitted uncritically from one generation to the next. This dismissal of an entire faith tradition and its 1.6 billion adherents around the globe stems from a long pattern of Western representations of “the other” that 1) describe a collectivity rather than recognizing individual identities and 2) presume to speak authoritatively without taking the subjects’ own perspectives into account. The problem did not originate with the modern missionary movement, but American missionaries were among the Orientalist thinkers who adopted this mode of discourse on the Muslim populations they encountered in the Middle East.

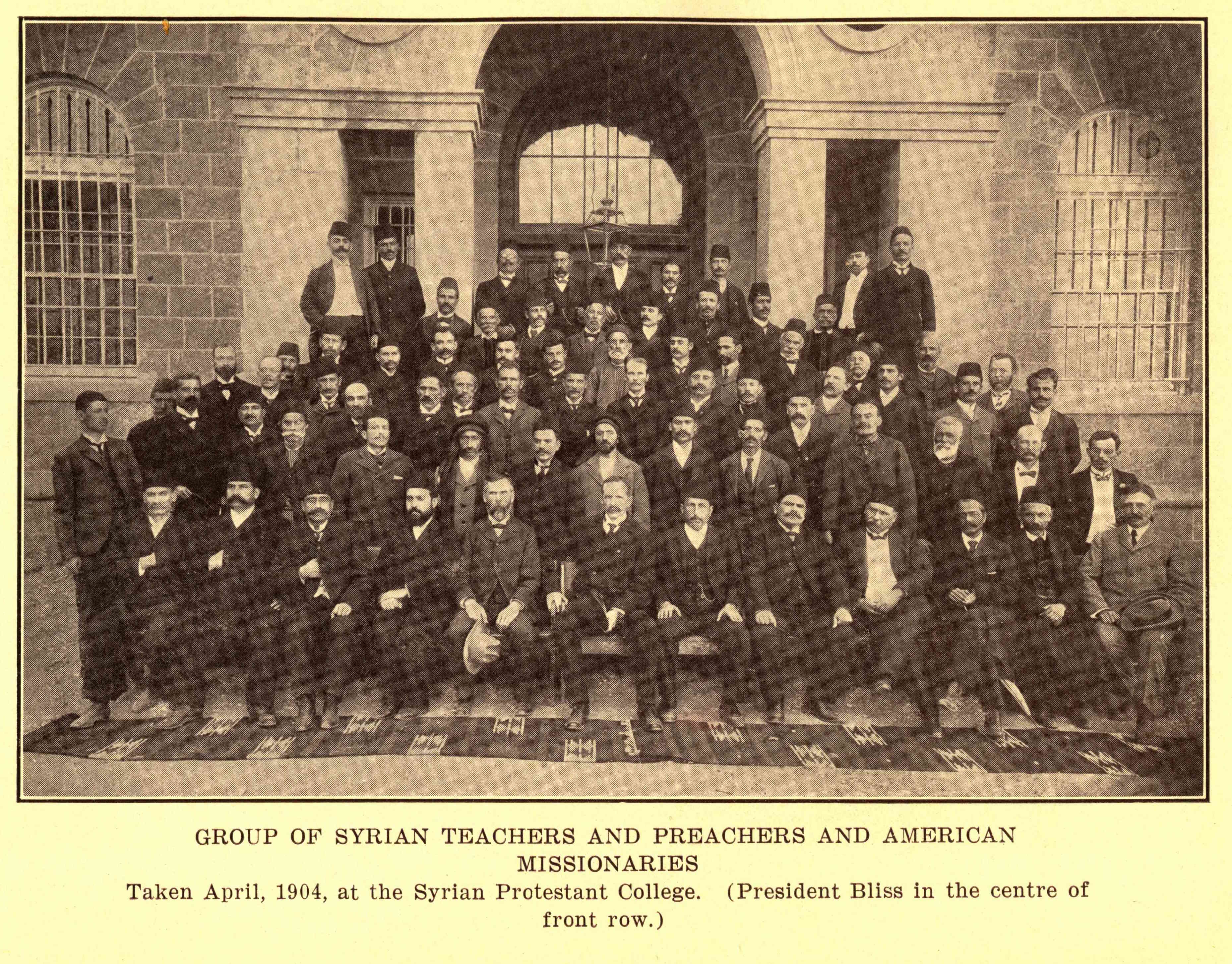

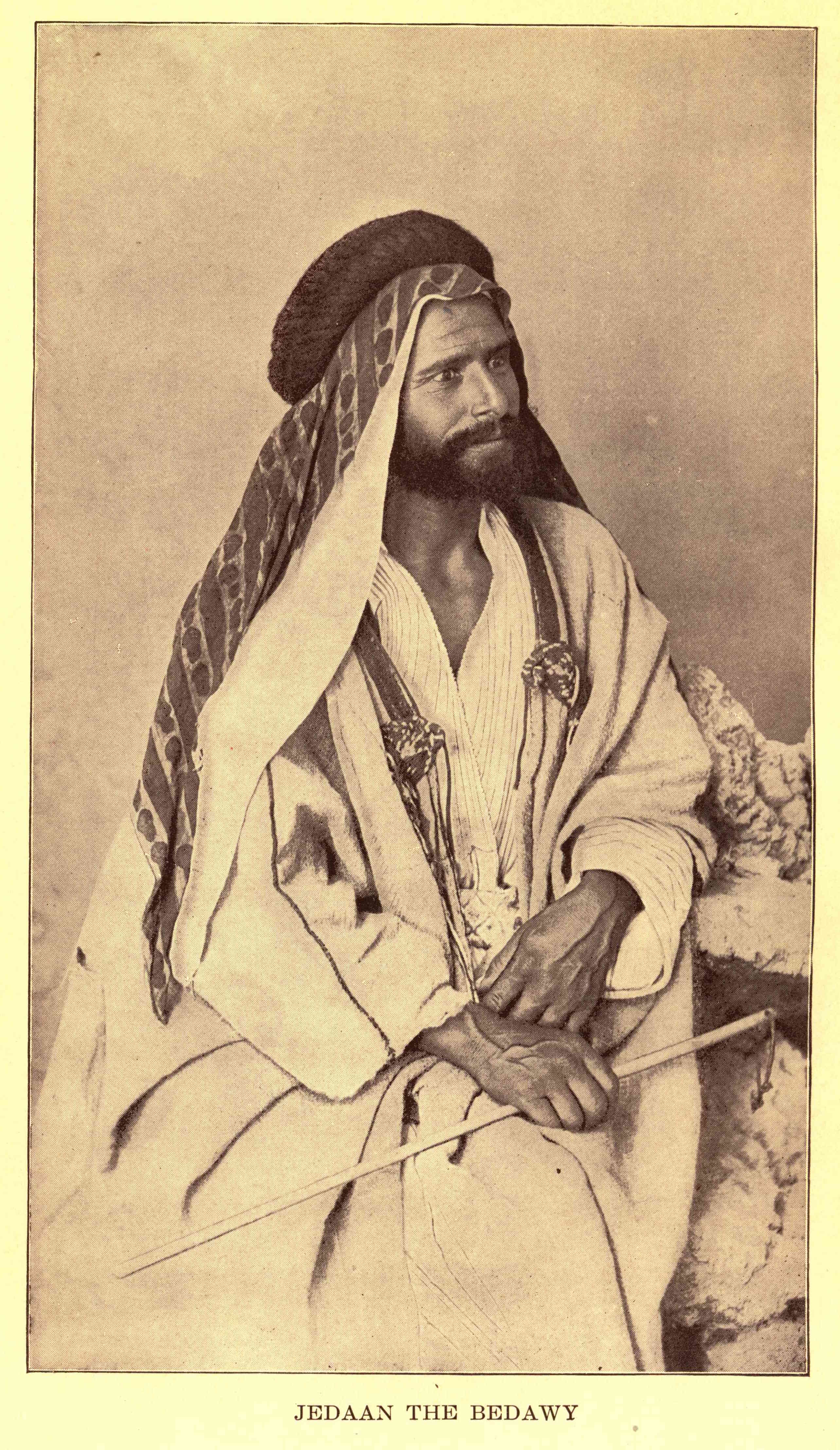

American Protestants established their first Mediterranean mission in Beirut, in a region  known as Ottoman Syria. The Presbyterians and Congregationalists who initiated Protestant schools, churches, and a printing press in Syria were among the first Americans to sustain long term contact with the Islamic world and to transmit information about Muslim society to readers back home. Missionaries like Henry Harris Jessup (1832-1910) may not have intended to mislead American mission supporters. Yet mission reports on the status of Muslim women, the despotism of Islamic rule, and the doctrinal errors of Islam were filtered through a narrow interpretive framework that served an evangelical Protestant purpose. The superiority of Western Christian civilization over Islamic society became an authoritative narrative (even though some missionaries took a more tolerant approach), and it was only when a Muslim converted to Christianity that he or she was named and set apart from the masses. As conversions were rare, these individuals became like trophies to display the missionaries’ hard-won victories. Gideon ‘Aoud, a Bedouin whose image appeared in multiple missionary publications, was one such prized convert.

known as Ottoman Syria. The Presbyterians and Congregationalists who initiated Protestant schools, churches, and a printing press in Syria were among the first Americans to sustain long term contact with the Islamic world and to transmit information about Muslim society to readers back home. Missionaries like Henry Harris Jessup (1832-1910) may not have intended to mislead American mission supporters. Yet mission reports on the status of Muslim women, the despotism of Islamic rule, and the doctrinal errors of Islam were filtered through a narrow interpretive framework that served an evangelical Protestant purpose. The superiority of Western Christian civilization over Islamic society became an authoritative narrative (even though some missionaries took a more tolerant approach), and it was only when a Muslim converted to Christianity that he or she was named and set apart from the masses. As conversions were rare, these individuals became like trophies to display the missionaries’ hard-won victories. Gideon ‘Aoud, a Bedouin whose image appeared in multiple missionary publications, was one such prized convert.

Pictured in a traditional headdress and flowing robes, Gideon represented what American efforts might accomplish in a region that missionaries defined as morally and culturally backward. I was intrigued, but not surprised, to find the same photo on the reprinte d copies of Jessup’s autobiography, Fifty-Three Years in Syria (1910), available today through Amazon. The original edition of the book included Gideon’s photograph among the internal illustrations. Its movement to the front cover was a savvy marketing decision, for I suspect that readers today will readily accept the man in rugged tribal dress as the face of Ottoman Syria, even though most Beiruti men whom Jessup knew sported Western attire in their photos. I have yet to find an account of Gideon’s life that is not filtered through a missionary lens, but countless other Syrians – whether Protestant, Maronite, Muslim, or Druze – told their stories through personal memoirs and Arabic press publications. Their voices complicate the images of Islam put forth by missionaries a century ago and contest the prevailing view of innate historical tension between Christianity and Islam.

d copies of Jessup’s autobiography, Fifty-Three Years in Syria (1910), available today through Amazon. The original edition of the book included Gideon’s photograph among the internal illustrations. Its movement to the front cover was a savvy marketing decision, for I suspect that readers today will readily accept the man in rugged tribal dress as the face of Ottoman Syria, even though most Beiruti men whom Jessup knew sported Western attire in their photos. I have yet to find an account of Gideon’s life that is not filtered through a missionary lens, but countless other Syrians – whether Protestant, Maronite, Muslim, or Druze – told their stories through personal memoirs and Arabic press publications. Their voices complicate the images of Islam put forth by missionaries a century ago and contest the prevailing view of innate historical tension between Christianity and Islam.

Read Deanna’s article ‘Images of Islam: American Missionary and Arab Perspectives’ in Studies in World Christianity, 22.1

Deanna Ferree Womack is Assistant Professor in the Practice of History of Religions and Multifaith Relations at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia. Her research explores the cross-cultural and interreligious encounters between American missionaries and residents of Ottoman Syria in the pre-World War I period.