The collapse of the Ottoman empire in the wake of the First World War a century ago did not merely redraw the political map of the Middle East in its modern form – itself so hotly contested today by forces such as ISIS; it also marked the end of a tradition of Turkish rule in the Middle east that stretched back nearly a millennium. Since the eleventh century, most Arabs and Iranians had been ruled over by Turkish-speaking military elites whose origins lay in the steppes of Central Asia. Despite their origins from the fringes of the Islamic world or beyond, these Turks played a crucial role in shaping Islamic civilization as well as the demographic and linguistic map of the Middle East.

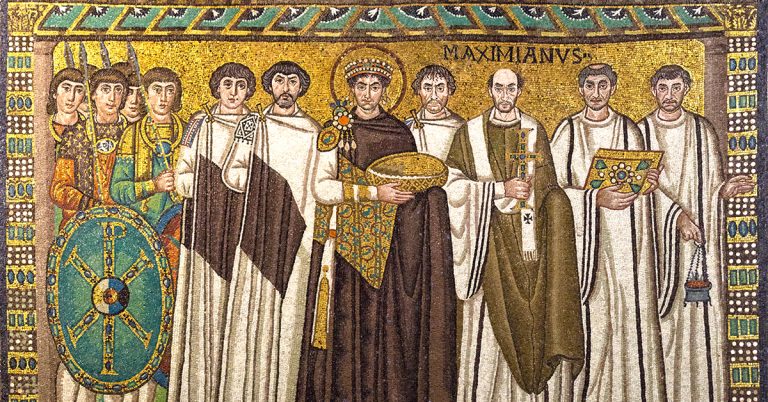

The conquest of the Middle East in the years between 1040 and 1071 by the first of these Muslim Turkish dynasties to rule there, the Seljuks, thus marks a turning point in the history of the region. Yet to contemporaries, Seljuk victories came as a bolt from the blue. Before about 1030, no one in the Middle East had even heard of these people, who were by origins nomads from the great Eurasian steppe, and whose chiefs retained close affinities with their steppe heritage. Accounts by contemporaries agree in describing the Seljuk Turks as an uncouth rabble, but existing Arab and Iranian dynasties crumbled before the advance of the Turkish nomads, who after establishing themselves in Iran and Central Asia, in 1055 seized Baghdad, the political centre of the Islamic world. Subsequent advances took them to the gates of Cairo and even to the shores of the Indian Ocean in Yemen and Oman. The vast area stretching from the Mediterranean shores of Syria to the borders of modern China came under Seljuk control, but their conquests also expanded the borders of the Islamic world. The Byzantine empire, which had defended itself successfully against Arab attacks since the seventh century, suddenly collapsed before the Seljuks, whose nomadic followers occupied Anatolia, laying the foundations for the eventual emergence of first the Ottomans and ultimately modern Turkey.

The Turkish speaking populations who first entered the Middle East with the Seljuks are their most tangible legacy today. Beyond Turkey itself, Turkish speakers live in Syria, Iraq, and above all Iran. The Seljuk period also left its distinctive mark on the institutions and even physical structures of Islam. The pencil-thin minaret that is today such a recognisable symbol of Islam seems to have been first introduced to the Middle East under the Seljuks, who spread it from their heartland in eastern Iran and Central Asia. Another Central Asian import was the madrasa – the religious school – which even today retains an important role as a medium of religious instruction in many parts of the Islamic world. Under the patronage of senior political figures in the Seljuk regime, the madrasa spread from eastern Iran to western Iran, Iraq and Syria, and was soon adopted in territories such as Egypt that lay beyond the Seljuk territories.

Under Seljuk rule a distinctive cultural synthesis emerged, combining Islamic, Iranian and Turkish traditions. The Seljuks remained proud of their origins in the steppe, where there was a long and prestigious imperial tradition, exemplified by conquerors such as the Huns in the fourth century and later the Mongols in the thirteenth. Yet as rulers of the core territories of the Islamic world, which had reached a peak of technological, cultural and economic development, they needed to make their rule acceptable to the existing predominantly Arab and Iran population. This they did by adopting the rhetoric of Islamic kingship, proclaiming themselves to be ‘sultans’ – a new title signifying ‘authority’ in Arabic that the Seljuks were the first dynasty to use officially, and they sought to portray themselves as defenders of Sunni Islam – their main rivals, the Fatimid dynasty of Egypt and the defeated Buyids of Iraq being Shiite. Not for the first or last time, sectarian differences were employed to support a political agenda. But the ancient Iranian tradition of kingship, stretching back to pre-Islamic times, was also invoked in Seljuk titles and iconography, and Persian became the main lingua Franca of the empire. The steppe tradition, meanwhile, continued to be represented by the stylised bow-and-arrow motif the Seljuks put on their official documents and coins, called the tughra, which signified authority on the steppe – the bow and arrow being the nomads’ weapon of choice. This synthesis of Islamic, Iranian and Turkish political traditions proved to be extremely influential, and was adopted by subsequent dynasties like the Ottomans; indeed, the Ottoman version of the tughra continued in use until the dynasty’s end in 1923.

Although the Seljuk dynasty collapsed in the late twelfth century, a branch of the family held on to power in Anatolia for another hundred years. For later generations in the Middle East, the significance of the Seljuks lies in their memory as ideal rulers owing to their promotion of Sunnism, and subsequently dynasties such as the Ottomans tried to prove they had a connection to them to legitimise their own rule. Beyond this myth-making, however, the Seljuks as the first Turkish dynasty to rule the Middle East made a crucial contribution to the formation of the political and religious traditions of the region.

A.C.S. Peacock is Reader in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of St Andrews, specialising in the mediaeval and early modern history of the Islamic world. His books include The Great Seljuk Empire (2015) and Early Seljuq History (2010).