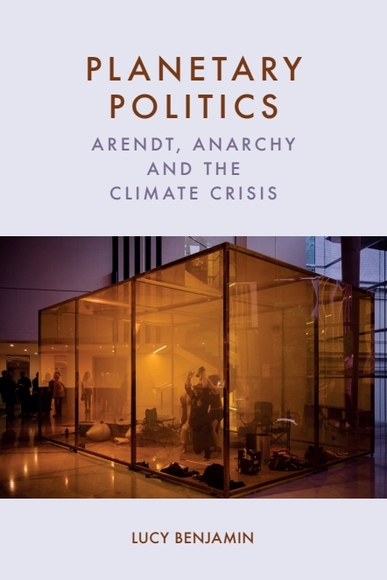

By Lucy Benjamin

Lucy Benjamin is the author of Planetary Politics, which explores the connection between ecological crisis and Arendtian politics of the earth.

This title is available as an Open Access ebook.

It would be impossible to isolate one aim within Planetary Politics. A scholarly claim might be made that the project of the book is to demonstrate an element of Hannah Arendt’s writings that has been overlooked. However, given the book’s commitment to Arendt’s account of thinking’s practical force, and the fact that Arendt herself condemned the idea of thinking in isolation from the events of the world, the real aim is to relocate Arendt’s thinking in the world. If I were to summarize my own intentions then, I would argue that the aim of the book is to refocus and reframe how we understand the meaning of a political life given the reality of the climate crisis.

Hannah Arendt has long been described as a prescient writer (including in another Edinburgh University Press title), one whose thinking dissolves the boundaries of theoretical disciplines, and whose writings consistently demonstrate the radical implications of failing to think. Arendt was a monumental figure in her own right; she was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933, after which she fled Germany, was detained again in a French internment camp, and was ultimately stateless for 11 years before being naturalised as a citizen of the United States. During this time, her commitment to political activism grew — as did her wariness of the supposed inalienability of human rights. She wrote widely and unflinchingly about a range of topics, but when I began this project in 2018, there was very little written about the intersection of Arendt’s writing and the planetary crisis of climate change.

And yet, as I started to investigate the possibility of bringing Arendt’s work into dialogue with this crisis, I saw that she had already written extensively about the ethical obligations of living an earthly life. And so, what I uncovered early on in this project was the existence of a well-developed, if overlooked, understanding of the kinds of obstacles with which we are now forced to contend.

What was clear to me at the outset was that Arendt’s argument regarding the failure of the imagination to provoke acts of critical reflection was laid bare in the context of climate change. Indeed, I was first compelled to pursue the environmentalism of Arendt’s thinking by my suspicion that the kind of complacency that now defines our response to the urgency for planetary-scale change was already examined and exposed in her work.

In Arendt’s final work, The Life of the Mind, she defines the project of political life in connection to the fact that we live on earth, writing that ‘plurality is the law of the earth.’ Plurality is one of Arendt’s most readily deployed terms, one that captures the inherent difference of human communities. As a principle of equality through difference, plurality is a term that enables us to advocate for the tolerance, understanding and shared, if differentiated, notions of responsibility. Yet it is also a term that assumes meaning by virtue of that common ground on which and by which we all live: the earth.

Arendt offers her first account of plurality in terms of human earthliness, in what is undeniably her most well-read book, The Human Condition. Here she defines plurality as corresponding to the fact that humans in their plural (rather than the human in their singular) ‘live on the earth and inhabit the world.’ This move from the givenness of life to the cultivation of inhabitation marks the development of political organisation and corresponds to the emphasis she places on the political force of action. What it also does is foreground the fact that political life is bound to and defined by its original relationship to the earth. Taking this point seriously not only means rethinking the political implications of actions that impact the earth, as in the need to repair the scars left by toxic contamination or waste disposal. Instead, it makes clear that politics does not happen on earth by chance. We only live political lives because we are earthly. If we took that reality seriously, if we actively thought about rivers, winds, trees, soil and worms as things that determine our political lives and not simply as the inconsequential ecological props that colour life, we might begin to have a different understanding of what it means to assume a political life.

The point of Planetary Politics then isn’t to learn how Arendt might have thought about the individual elements of planetary existence as though she might be ventriloquised to speak to our times. Instead, the point is to ask what a meaningful politics might be, given that politics was always already planetary.

About the author

Lucy Benjamin is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. She obtained her PhD in Comparative Literature from Royal Holloway, University of London in 2021. From 2022-2024, she was a postdoctoral fellow in architectural philosophy at the University of Melbourne, during which time she was also a visiting fellow at the Australian National University. In 2025, she was awarded the Young Scholars Laureate by the Walter Benjamin Kolleg. Lucy currently works on the politics of repair and the possibility of rereading architectural theory according to the neglected ideas of feminist architectural thought. Her next monograph will be an engagement with Hannah Arendt’s architectural and spatial thinking.