by Maciej Kurzynski

In recent decades, literary scholarship—especially in area studies—has functioned much like a mathematical function. It takes two inputs: a defined corpus of texts (often the established canon) and the historical narrative surrounding their emergence. The generated output is an interpretation, typically an article or monograph, that highlights the political, ideological or cultural meanings arising from the interaction between text and time. We might represent this schematically:

f(texts, history) = interpretation

The influence of this approach becomes especially clear when examined across different literary traditions. One might move from an English literature department to a French or East Asian literature department and encounter strikingly similar discussions of ‘modernity’, albeit centered on different texts and different national contexts. In many cases, one could substitute names and place references with their counterparts from another national background and the core scholarly narrative would remain intact.

Consider the following excerpt from a recent literary history book:

“Imported printing technology, innovative marketing tactics, increased literacy, widening readership, a boom in the diversity of forms of media and translation, and the advent of professional writers all created fields of literary production and consumption that in the preceding centuries would hardly have been imaginable. Along with these changes, [xxx] literature—as an aesthetic vocation, scholarly discipline and cultural institution—underwent multiple transformations to become ‘literature’ as we understand the word to mean today.”

I have deliberately removed the cultural tradition’s name and the source attribution. This passage could be inserted, almost verbatim, into numerous literary histories across different national traditions.

The single-function approach, sometimes called ‘genealogy,’ is rigorous and has produced some of the most influential works in the humanities. It requires meticulous attention to historical events, deep familiarity with texts and the ability to construct a coherent narrative across extensive analysis. As Jo Guldi notes, historicist methodology resists a ‘world without history‘—an ‘imaginary territory that is home to students of statistics and machine learning’ and often lacks reflection on cultural and political revolutions.

However, while ‘machine learning’ might be legitimately criticized for its dehistoricized approach to data, it can also strike back. In particular, the recent surge in computational power and the conceptual frameworks associated with large language models (LLMs) invite a critical re-evaluation of ‘literary history’ as a single-function approach. Just as LLMs process language across multiple layers, capturing not only syntax and semantics but also broader contextual nuances, human engagement with texts also constitutes a multi-layered and poly-temporal phenomenon. Narratives are not mere reflections of their historical moment; they are dynamic constructs shaped by deep-rooted storytelling traditions, universal cognitive processes, and evolving contemporary sensibilities, some culture-specific, some not.

Beyond the Single Function

In my recent article, ‘Poly-Temporal, Multi-Layered: A Techno-Cognitive Theory of Narrative Experience in Literature‘, I develop this argument by reframing literature through the problem of experience. This connects both the production (decoding) and reception (encoding) of literary texts within a framework that draws on parallels between artificial and natural intelligence.

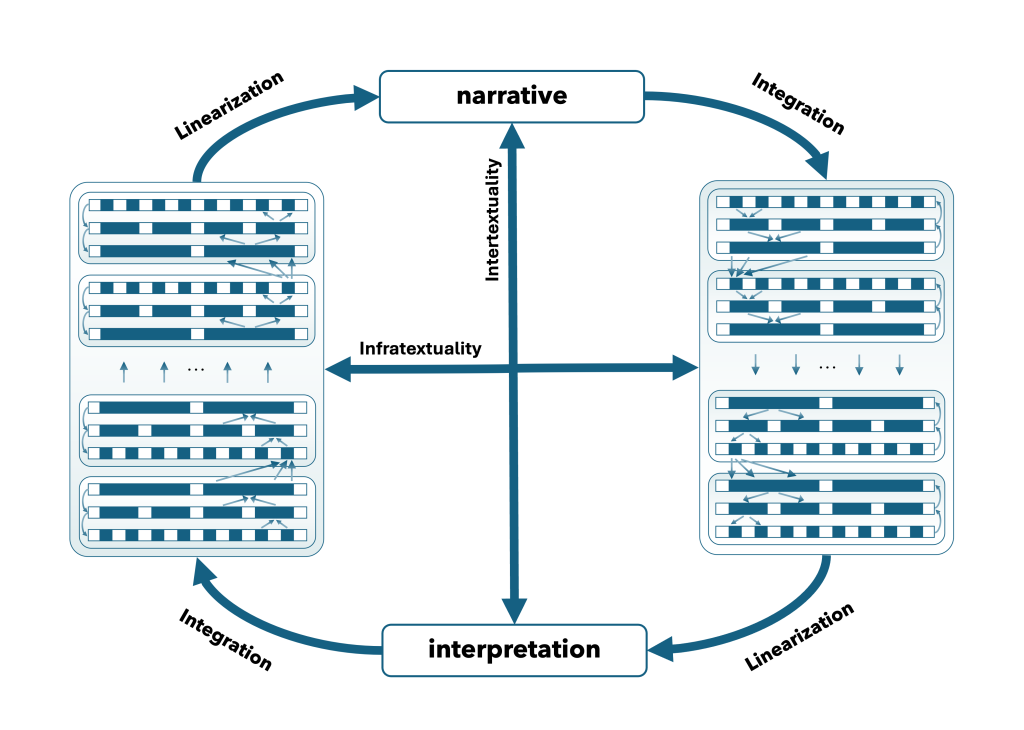

Large language models show how a linear sequence of words can be encoded into multi-layered, hierarchical representations. This mirrors the human brain’s own layered approach to language processing, where sensory inputs are integrated into increasingly abstract conceptual structures. Conversely, in language production (text generation), hierarchically encoded information is re-linearized (decoded) into a one-dimensional sequence communicated to the outside world.

From this perspective, literary ‘history’ (though at this point, can it still be called history in the traditional sense?) occurs when the alternating processes of integration and linearization introduce changes into the transmitted information. These changes are inevitable, since it has so far been impossible to transmit encoded representations directly between brains; linearization, like any dimensionality reduction, necessarily loses some aspects of the information, thus making change in the literary record possible.

Embracing the techno-cognitive framework, even at an abstract level, has the potential to transform literary studies. It holds the promise of breaking down the self-enclosed scholarly communities and disrupting the national chronologies to which they often adhere, fostering a genuinely interdisciplinary collaboration focused on new questions. It encourages a shift from seeing literature as a single input-output function to understanding it as a dynamic, recursive phenomenon—one that better reflects the beauty of narrative art and human thought.

Read ‘Poly-Temporal, Multi-Layered: A Techno-Cognitive Theory of Narrative Experience in Literature‘.

About the journal

IJHAC is one of the world’s premier multi-disciplinary, peer-reviewed forums for research on all aspects of arts and humanities computing. The journal focuses both on conceptual and theoretical approaches, as well as case studies and essays demonstrating how advanced information technologies can further scholarly understanding of traditional topics in the arts and humanities.

- Sign up for TOC alerts

- Subscribe to IJHAC

- Recommend IJHAC to your library

- Submit an article to IJHAC

About the author

Maciej Kurzynski is a Research Assistant Professor at the Advanced Institute for Global Chinese Studies, Lingnan University, Hong Kong. He holds a Ph.D. in modern Chinese literature and culture from Stanford University and had previously studied at the University of Warsaw (B.A.) and Zhejiang University (M.A.). In research and teaching, he draws inspiration from affective neuroscience and machine learning to experiment with texts and expand the traditional boundaries of literary studies.