By Benjamin M. Studebaker

Is Donald Trump going to establish an authoritarian regime in the United States? Did Boris Johnson have the same potential in the UK? I really don’t think so, and Legitimacy in Liberal Democracies is about why.

The United States and the United Kingdom are what I call ‘embedded democracies.’ Because their political systems are very old, it’s hard for citizens of the US and UK to imagine an alternative political system for which they’d be willing to fight and potentially die. The agedness of the US and UK changes the character of political crises in these countries in two ways. First, national identity becomes positively associated with the political system. Being ‘American’ or ‘British’ comes to involve an identification with the constitution or with the Westminster system. Second, because the US and UK have outlasted many other political systems, historically, there is a lack of confidence in alternatives. People in other parts of the world have tried communism and fascism in a variety of ways, but very few of these regimes have lasted the test of time. So, even when citizens in the old, aged democracies come to believe their political systems are dysfunctional in various ways, they continue to believe that the other systems that have been tried or might be tried are even worse.

The US and UK are not special or exceptional countries. Their democratic systems are not ‘better’ than those of other democratic states. They are simpler older. Democratic systems don’t have to be particularly good to become embedded. Indeed, becoming embedded comes with its own set of problems.

Credit: Nicolas Raymond

Legitimacy crises in young democracies

In younger democracies, a legitimacy crisis poses a threat to the democratic system. Citizens lose belief in democratic procedures, and so they adopt belief in old or new alternatives. A gap opens up between the state and the citizens, and the state is forced to find a way to close that gap. Sometimes it represses dissent. Sometimes it makes concessions. Sometimes it fails to do both, and there’s a revolution.

Deep pluralism in embedded democracies

In embedded democracies, citizens who lose belief in democratic procedures don’t believe there’s a credible alternative available. So, even as they become frustrated, they don’t take the forms of action they would have taken if they lived in a younger democracy. They don’t organize for revolution. Disagreements that would have produced revolutionary disturbances become compatible with the maintenance of the democratic system. I call this condition ‘deep pluralism’: it’s an unprecedented level of conflict that is nonetheless sustainable because of embeddedness.

Legitimacy crises with deep pluralism

This doesn’t mean disgruntled citizens do nothing. They try to reform democratic procedures, in various ways, to make them work better. They try to change the electoral system; the relationship between elected officials and the bureaucracy; the relationship between states and regions and the central government; the relationship between the branches of government; or the relationship between the central government and supranational structures like the European Union or the World Trade Organization.

Deep pluralism prevents citizens from developing a shared understanding of what’s wrong with their democracies. They adopt a variety of different views about which reforms are necessary to purify the system. The only thing the citizens agree on is the lack of an alternative to democracy, on the undesirability of authoritarianism. So, the most effective way for citizens to oppose the procedural reforms they don’t like will be to argue that those reforms have an authoritarian character.

This means that there will be a lot of concern about authoritarianism precisely because it’s the one thing everyone hopes to avoid. This concern with authoritarianism causes different factions of reformers to obstruct one another, making it difficult for the state to act. The state is protected from revolution, but at a cost to its dynamism and adaptability.

The proliferation of legitimation stories

In this situation, the state needs to find a way to make up for its creeping inability to act. It does this by generating an ever-greater variety of what I call ‘legitimation stories.’ These legitimation stories are attempts to explain why state action ought to be regarded as acceptable. They tie something the state does to a human value, a ‘legitimating abstraction.’ In showing that this act is connected to this value, the state conceptualizes the abstraction, making it concrete and real. For instance, when the UK left the EU, it claimed, through a variety of politicians, that it did this to advance the freedom of British subjects, to represent their will, to make the country more prosperous, and so on. Each of these abstractions – freedom, representation, prosperity – was tied, through sets of arguments, to the state’s action.

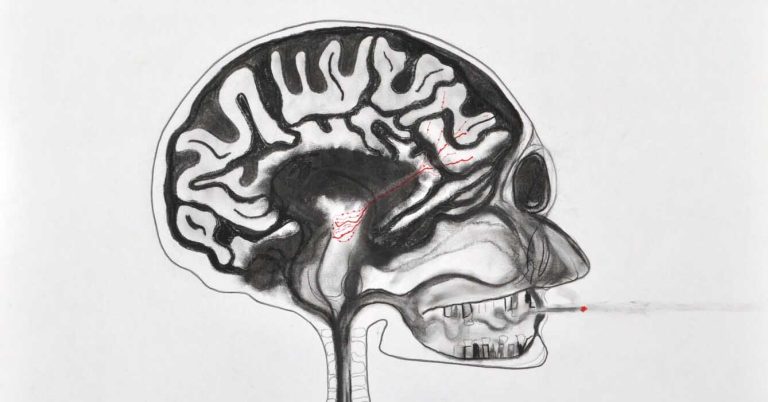

Deep pluralism makes it difficult for the state to build consensus around any action and therefore around any particular legitimation story. It becomes necessary for states to use many different, conflicting legitimation stories at the same time. The conflicts among these stories further intensify factionalism. All stories come to appear false to significant parts of the population, and in this sense all stories appear ideological. Yet, all stories also remain persuasive for some parts of the population, and in this sense they all continue to perform a legitimating function. Citizens become lost in this forest of narratives, in this legitimation hydra.

The more stories proliferate, the deeper pluralism becomes. And so, in an effort to generate support for state action, the state makes it even harder for itself to act going forward. Think of an embedded democracy as a hydra stuck in a tar pit. By growing more heads, it finds ways to breath, to eat, to sustain itself. But the heads pull the beast in different directions. They slam into each other with great force. They have an enormous weight. And so, the more heads there are, the more activity there seems to be – but the more stuck the beast becomes.

About the author

Benjamin M. Studebaker received his PhD in Politics and International Studies from the University of Cambridge. He is the author of Legitimacy in Liberal Democracies, in which he explores how legitimacy should be treated in countries where authoritarian alternatives to democracy lack credibility.

About the book

In Legitimacy in Liberal Democracies, Benjamin M. Studebaker develops a theory of legitimacy to explain the crisis of liberal democracy in established democracies such as the US and the UK.

In these countries, there is deep dissatisfaction with political procedures, yet no credible alternatives have emerged. Without alternatives, the crisis cannot produce revolution. Instead, Studebaker suggests that the disagreements that ordinarily lead to political violence instead proliferate throughout the state and society. The result is a legitimation hydra – a state, burdened by an excess of narratives, that struggles to take any action at all.