By Bryony Coombs

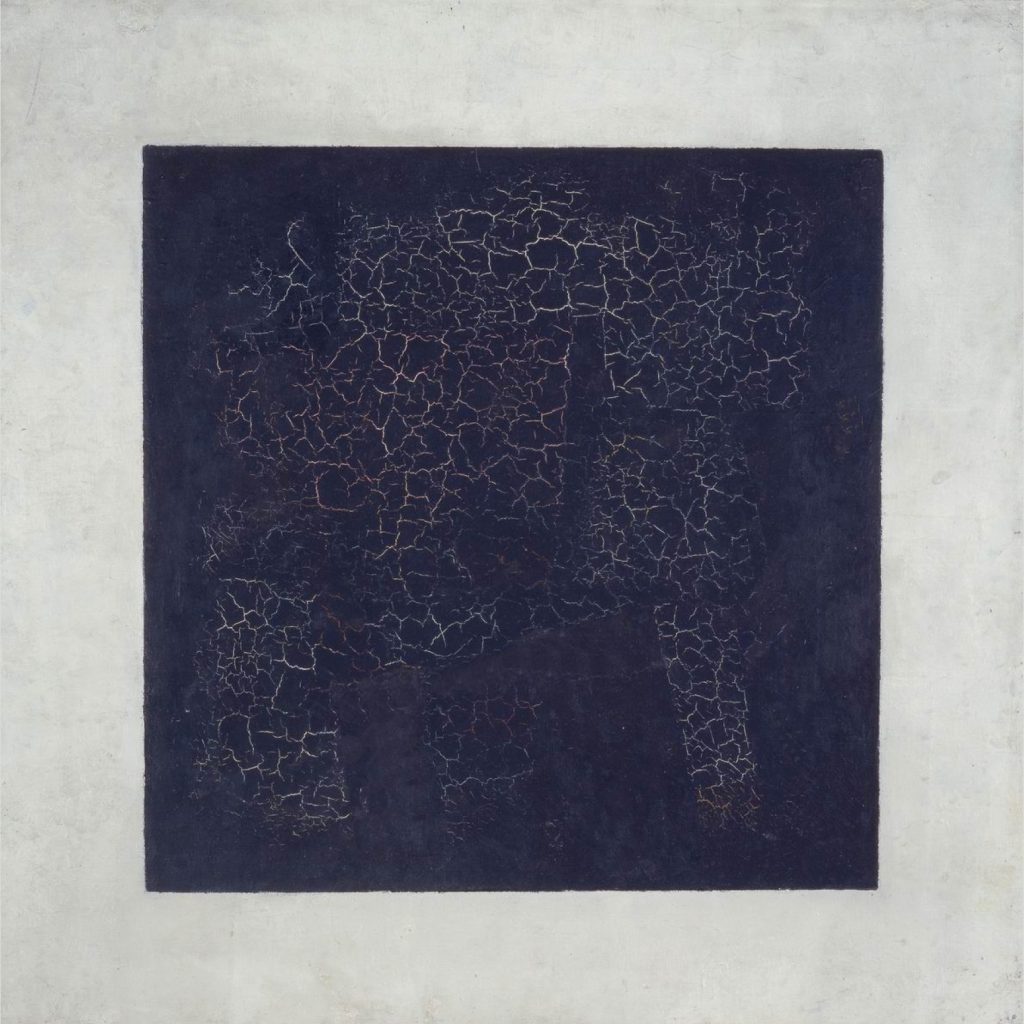

It was the first time someone had made a painting that wasn’t directly representing something. At least it has often been discussed in these terms. Around 1915 the Kiev-born artist Kazimir Malevich took a canvas of 79.5 cm x 79.5 cm and painted it white around the edges and then, with thick black paint, composed a black square. Malevich became the artist of one of the most famous, enigmatic and, for some, unsettling of images.

In 1915, Malevich wrote:

‘Up until now there were no attempts at painting as such, without any attribute of real life… Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself.’

That the painting potentially also had some spiritual significance is suggested in the way it was displayed. When exhibited in The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10 held in St Petersburg in December 1915, Black Square was placed high up on the wall across the corner of the room, the same sacred place that a Russian Orthodox icon would occupy in a traditional Russian home.

This was not, of course, the first attempt to make a painting that wasn’t of something, as any medieval art historian will tell you.

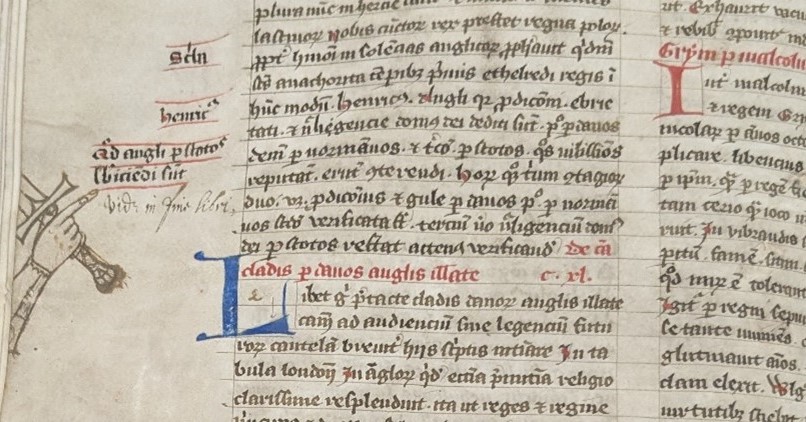

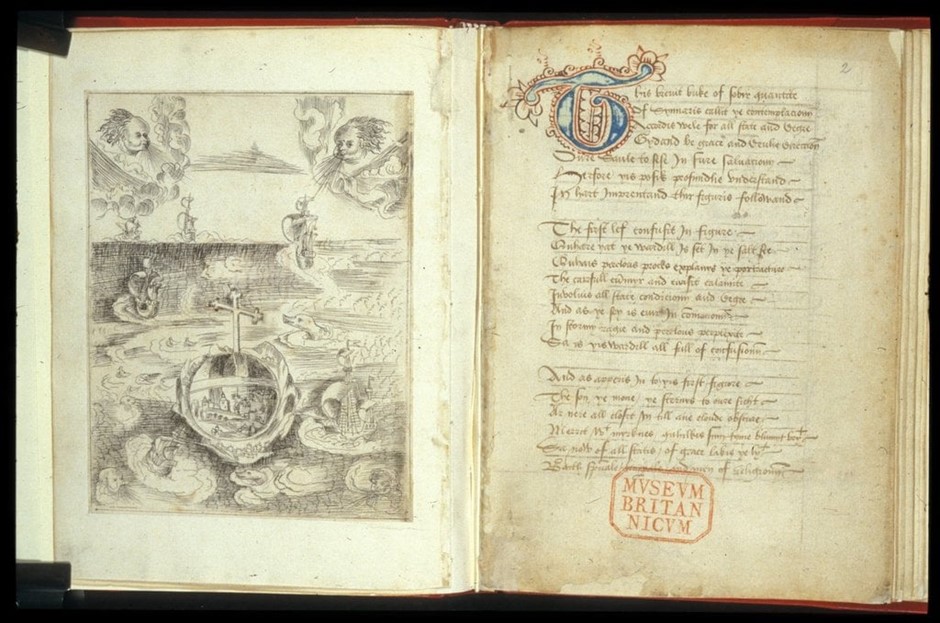

A month ago, I was in the British Library, London, conducting research for my forthcoming monograph Scotland on Parchment, a work tracing the development of manuscript illumination in late medieval Scotland. I had called up an intriguing manuscript about which not a great deal had been written. The composition of the text dated to c.1494, whilst the manuscript itself dated to c.1545. The work, a poetic composition called the Contemplacioun of Synnaris, had been attributed to a medieval Scottish Friar, William Touris. The poem was structured in sections corresponding to the days of the week with seven topics examined: the vanity of the world, man’s potential for good or evil, sin and death, judging the soul, Christ’s Passion, the torments of hell and the joys of heaven.

The poem included a structural progression from the concerns of the individual to the broader concerns of humanity. Immediately of note, was that each section was prefaced by a visual image – a pen and ink drawing in the style of an engraving. When an edition of this text was published in 1955, the editor J. A. W. Bennett recognised the integral part that the images played in the project and published six of these along with the text, omitting just one – the third.

It is this third image which stopped me in my tracks in the British Library. The image stands alone in the manuscript for its simplicity as a neatly coloured plain black square.

The black square was not deemed necessary to reproduce presumably due to its simplicity in relation to the other complex religious and moralising images. It was clear that this was just a plain black square and as such was not worthy of reproduction. It is however this image and its intriguing explanatory text which, for all its apparent simplicity, is so enlightening.

When I examined the manuscript in-person the back square was unexpected, shocking even, in the context of such complex medieval theological ideas, but the text makes quite clear that this was the original and intended image. The black square evidently played a pivotal role in guiding the reader’s devotional meditations surrounding such thorny subjects as death and eternal damnation. The precise meaning of the Contemplacioun of Synnaris’ black square is elucidated by the words used to articulate the image. Crucially the image was thought to communicate something the words could not.

If we turn to folio 16v in the manuscript, therefore, we find a relatively plain, hand-drawn, black square. The square is executed on paper affixed to the manuscript folio. It was executed approximately 419 years before Malevich had a similar idea and sought to communicate similar ideas through the same shape, colour and form. If we look closely at the manuscript, we can see that it has been meticulously ‘coloured in’ with the same fine-nibbed quill that was used for the other more complex drawings. The text leaves us in little doubt as to how we should read the image:

‘This third leif with coloure sad of sabill

Signifeis of syn ye sad remembraunce’

The third leaf with colour sad of sabill [sabill or sable being a heraldic term for black] / signifier of sin, your sad remembrance.

Touris’ black square was used to communicate the abyss of death and the lack of hope in eternal damnation. Later in the manuscript, we find a detailed imagining of the complex torments of hell, but it is precisely the lack of form, light and detail in the black square which is so arresting for the reader. One can only assume that the impact on a late-medieval audience was similar. In 1906 Mark Twain noted that there is no such thing as a new idea and as a medievalist there is a great fascination at times in watching this play out.

Malevich certainly knew nothing of my Scottish friar’s black square and yet the mental gymnastics that he undertook to communicate the abstract idea of death and potential spiritual perdition are analogous. Few of our artistic impulses are truly original and it can be unnerving to witness the same visual and intellectual solutions being reached in such geographically and temporally dislocated examples.

All images in the public domain. Note: Select Manuscripts at the British Library may not be photographed by readers. Since the British Library cyber-attack in 2023, photographic services have not resumed and therefore an image of the black square from Harley 6919 is still, for the moment, unavailable.

About the Book

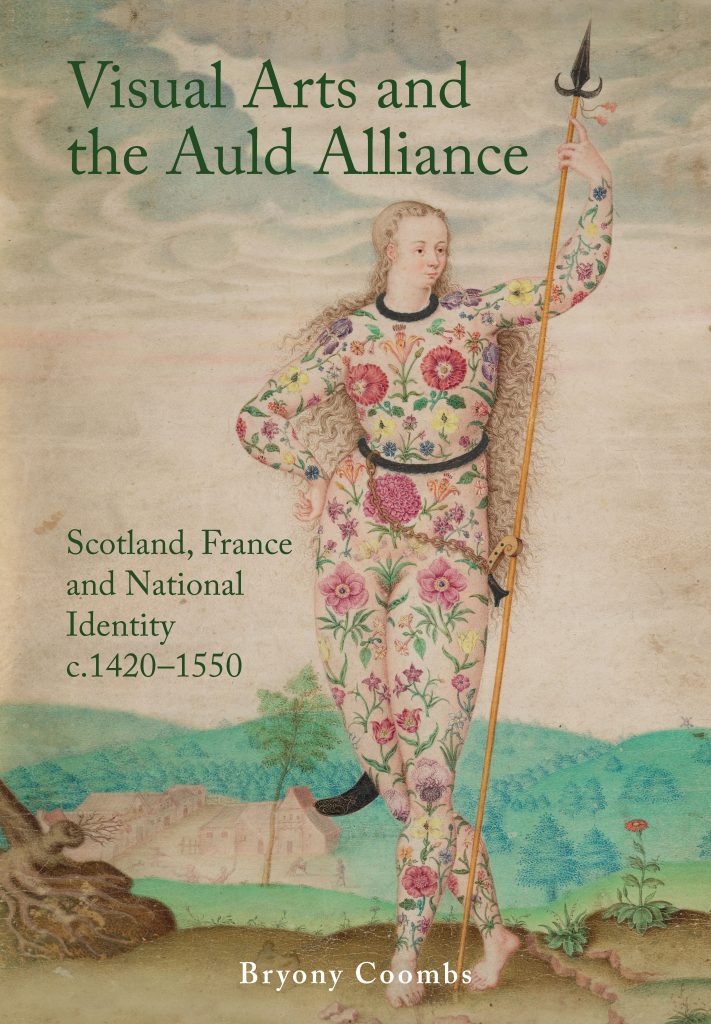

Visual Arts and the Auld Alliance explores the links between patronage, identity and Franco-Scottish relations in the late medieval and early modern periods.

‘This is an important study that will be required reading for anyone interested in the cultural and political history of late medieval and early modern Scotland. More generally, Coombs’s work offers a striking contribution to wider debates about the potential use of art to convey, express or encourage a range of political and cultural ideas and to articulate notions of both difference and belonging.’

– Professor Steve Boardman, University of Edinburgh

About the Author

Bryony Coombs is Renaissance Teaching Fellow in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. Her first monograph, Visual Arts and the Auld Alliance: Scotland, France and National Identity c.1420-1550 will be published by Edinburgh University Press in September 2024, and she has recently signed a contract for her second monograph, Scotland on Parchment: Illuminated Manuscripts in Late-Medieval Scotland with Edinburgh University Press in their new Visual and Material Cultures of Scotland Series. Bryony was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (FRHistS) in May 2024 and has been the recipient of the Murray Medal for History (2019) and the Jack Medal (IASSL, 2021).

Explore related articles on the EUP Blog

Abstraction for all? Thoughts from the author of Abstraction in Modernism and Modernity

Excerpt from ‘Image-Thinking: Artmaking as Cultural Analysis’

EUP 75: Our Publishing in Art and Visual Culture