By Tanvir Akhtar Ahmed

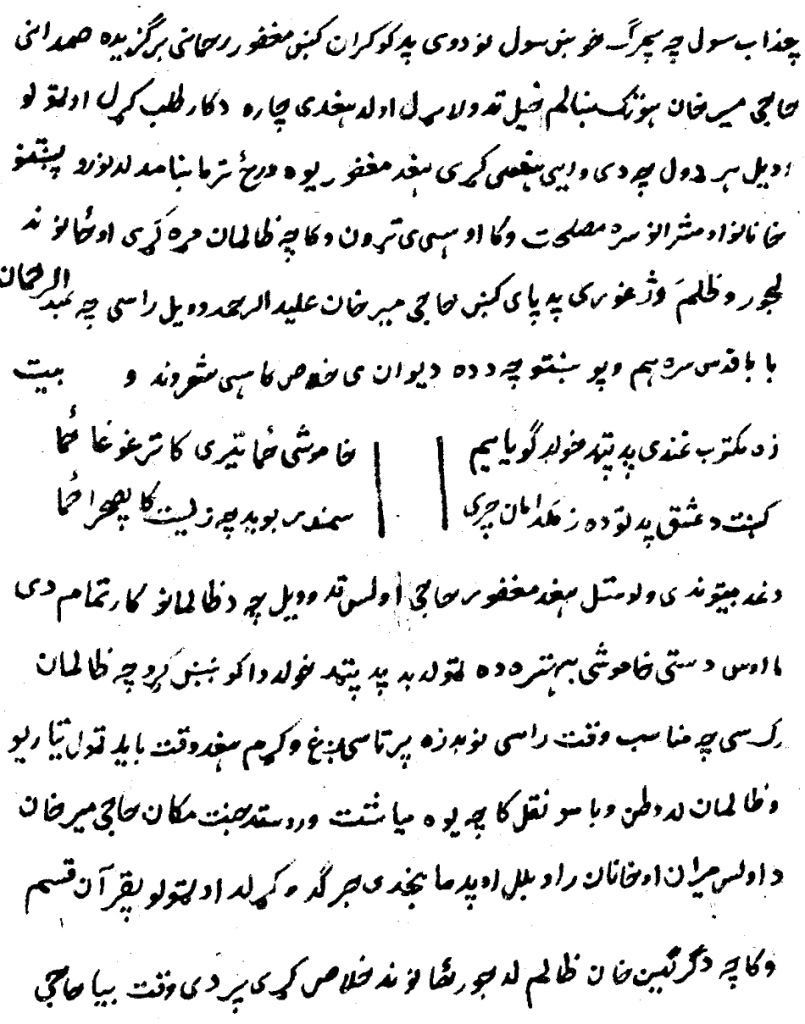

One evening in 1709 C.E., after a long journey from Kandahar, Mīr Ways Khān fell asleep at a shrine. Some say the shrine was the Prophet Muhammad’s grave in Medina, and that Mīr Ways Khān was visited that night by the Caliphs Abū Bakr and ʿUmar in a dream. Others maintain that the shrine was that of the Eighth Imam, ʿAlī Riżā, in the city of Mashhad, and that it was an angel who came to Mīr Ways Khān with a God-given message. A different party still relates that Mīr Ways Khān fell asleep in the Sacred Precincts of Mecca, and that he dreamt of nothing at all; but when he woke up, he found that his scabbarded sword had been mysteriously unsheathed.

Miraculous Edges

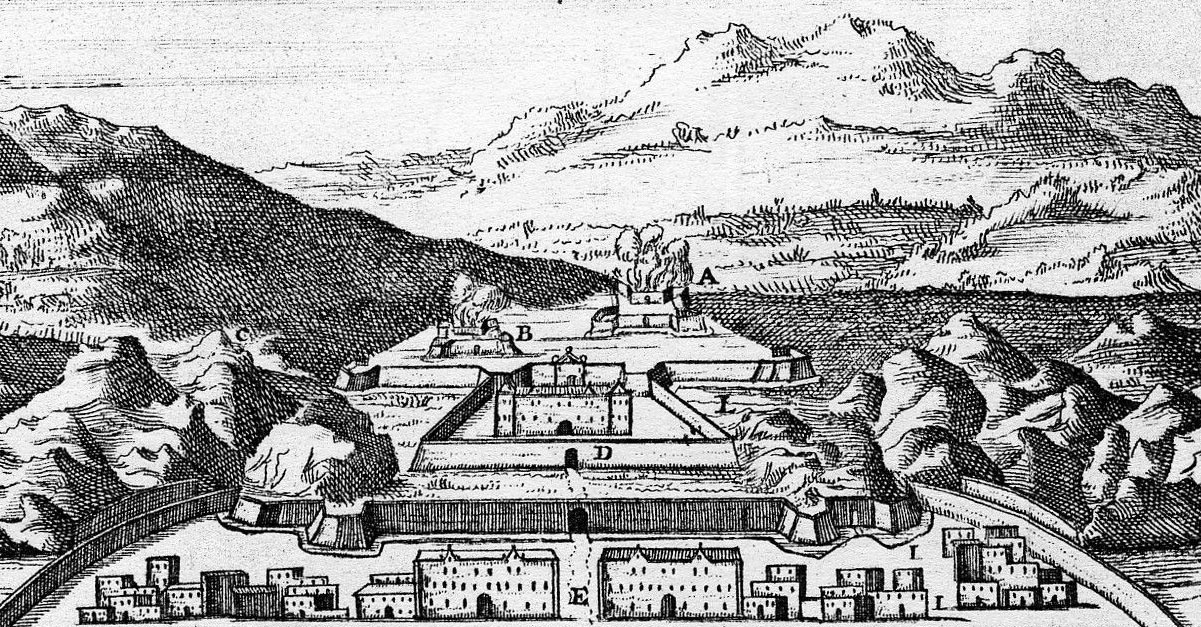

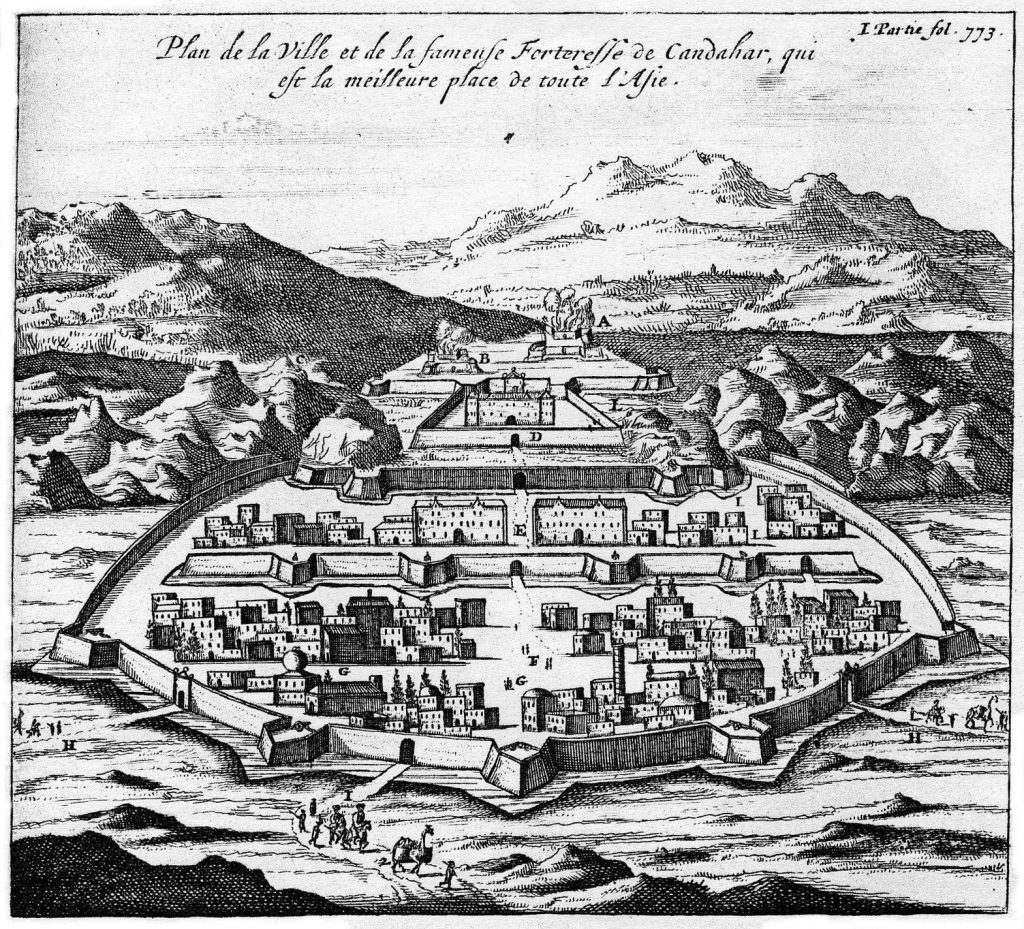

Mīr Ways Khān—or Ḥājjī Mīr Khān, as he would come to be known—went on to lead a successful uprising against the Safavid governor of Kandahar. Many histories would have us understand that uprising in the context of empires: as part of a long competition between Safavids and Mughals, as an event that marks the murky transition between Safavid and Afsharid regimes, as the dawn of the Hotak dynasty. Others would have us make sense of the rebellion through explanations of ethnic and sectarian difference: Afghans against foreigners, Sunni subjects against Shia sovereigns.

It is precisely these heuristics of empire and ethnicity and confession that are normative today in speaking about Afghan contexts. Such heuristics buttress the portrait of a “graveyard of empires” within which violence is more natural than anywhere else. The trinity of empire, ethnicity, and confession assure us that it is not conquest and capital that provoke violence in Afghan history. Violence is simply endemic to Afghans themselves.

The record of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’s uprising lets us strike a different path. Our accounts of the rebellion are disturbed by strange and startling events which defy the normal workings of historical time. As Ḥājjī Mīr Khān moves towards the inevitable conclusion of revolt, he is said to have been haunted by unseen voices at sacred shrines; to have found the gray skies above him cracked apart by sunlight while he recited mystical lyrics; to have become the embodiment of a dervish’s long-ago prophecy on the banks of the Tarnak River. The edges of the rebellion’s record are miraculous ones.

Often enough, those miraculous edges are reduced to nothing more than historiographical chaff to be cut away from the real stuff of history. It somehow makes more sense to see the uprising as a Sunni/Afghan/Hotak movement against Shia/non-Afghan/Safavid opponents. Yet if this is the “true” character of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’s uprising, why are our records teeming with supernatural happenings? Why do we find it so easy to dismiss what others clearly felt was worth mentioning? What do we risk becoming through our commitment to glossing miraculous tales as either rhetoric or gobbledygook?

Troubling Dreams

When we glance at the uprising from its strange edges, the event that comes into view breaks with today’s prevailing metrics. We see a world in which Ḥājjī Mīr Khān seeks divine succor at the grave of the Eighth Imam, implicating him in longstanding habits of veneration that trample the common sectarian distinctions of today. We see him peer into the verses of the poet Raḥmān Bābā for a supernatural sign, embedding him within a millennium of bibliomantic practices across the Islamic world. We see Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’s mother, Nāzō Ana, offer her cheek as a young girl to a wonder-working saint, transgressing gendered norms to secure a radically reversed future.

Such stories and others de-exceptionalize Afghan history by weaving it into a global Islamic tapestry of pilgrimages, prophesies, dream visitations, celestial annunciations, and other extraordinary happenstances. Instead of offering us a parochialized vision of the Afghan past, the strange history of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān moves our gaze onto how Afghans have always been participating in diachronic transregional patterns of mysticism, thaumaturgy, and political longing.

That participation is more than a retort to racializing imperial historiographies. It can be a guide for us today in the struggle to better narrate the past. As shown by the debates with which I opened this essay, the details of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’s uprising have been a matter of argument across the centuries. Each of those contradictory tales are parts of Afghan history. They each show us the strange ciphers used to code meaning into the passage of time. Their incoherence and multiplicity signals not a shattered history, but the chance to narrate the past in a ceaselessly expansive way.

The accounts above establish a shared moment: that one evening in 1709 C.E., after a long journey from Kandahar, Mīr Ways Khān fell asleep at a shrine. Each account circumambulates that event in different ways. None of them can agree on what exactly Mīr Ways Khān dreamed. As a result, we too cannot establish the “facts” of those dreams. This is less of a historical loss than a generative wellspring of possibilities. The dreams of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān are best left as an open question, so that they might continue renewing the significances of Afghan pasts. The closest we might get to knowing Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’s dreams is to state that they are always comprised of the collective dream that is Afghan history, which can never be separated from the tangible circumstances of Afghans first and foremost. And if we return the troubled sleep of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān to its place in our narratives, attending to the many possibilities of his long night, perhaps we might also find a meaningful reminder, as conscious historians, in his inexorable waking.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the journal

Afghanistan is the journal of The American Institute of Afghanistan Studies, dedicated to the cross-cultural study of Afghanistan and its surrounding regions, delving into its rich history from a wide variety of humanities-focused angles.

Sign up for TOC alerts, subscribe to Afghanistan, recommend to your library, and learn how to submit an article.

About the author

Tanvir Akhtar Ahmed is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University. His work focuses on Islamic social movements, imaginaries, and philosophies of history between premodern Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. You can find more of his work in Afghanistan Volume 6, Issue 2 in the article: ‘Miraculous Edges of Rebellion: On the Strange History of Ḥājjī Mīr Khān’.