by C. Ceyhun Arslan

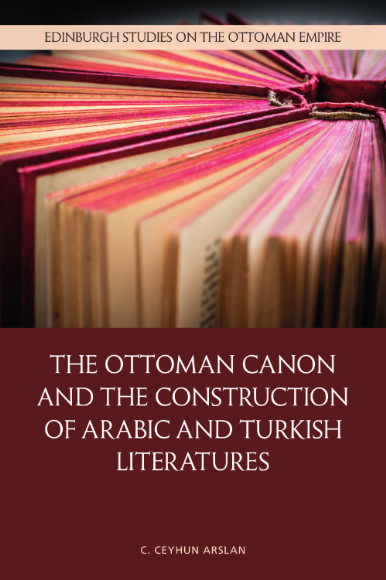

The author of The Ottoman Canon and the Construction of Arabic and Turkish Literatures talks about his writing process, the inspiration behind his new book, and the surprises he encountered along the way.

Tell us a bit about your book.

The Ottoman Canon is about how texts create communities. It examines how, for example, the pre-Islamic poems of Imru’ al-Qays contribute to the formation of both an Arab national and an Ottoman imperial consciousness. When we study literature, we often assume that a community produces a national literature that serves as a window into that community. Even books in Middle Eastern Studies reflect this assumption: their covers, unlike the covers of books on Western literatures, often display photos or manuscripts. These covers sometimes give the impression that they provide unmediated access to these communities.

I followed an alternative approach: I looked at how a multilingual canon of Arabic, Persian and Turkish works forms the community that Ottomanists have described as ‘the Ottoman literati’. In this way, my book differs from most works in Ottoman Studies which examine the texts that the Ottoman literati have produced. Furthermore, the Ottoman literati did not identify themselves as Persianate or Arabised even though they drew significantly upon Arabic and Persian works. My work, therefore, took a different path from the current research that examines how Persian works generated a Persianate world, or Arabic texts generated an Arabic cosmopolis.

What inspired you to research this area?

I had many sources of inspiration, but I will mention one that will surprise readers: academia. I have observed how a repertoire of texts helped me bond with scholars from different parts of the world, such as Lebanon, China and the USA, just as a set of texts reinforced the bond among members of the Ottoman literati. Likewise, as I witnessed the hierarchies and inequalities that mar modern academia, I became more attuned to all the exclusions that the Ottoman canon perpetuated.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

This book has taught me to look at the Ottoman past to envision new futures without romanticising this past. The Ottoman canon served as a springboard to flesh out and then transform the concepts and analytical paradigms that have dominated Middle Eastern Studies and Postcolonial Studies. I realised I could no longer take for granted that Ottoman literature emerged under the influence of Arabic and Persian literatures, or that Arabic works generate only Arab or Arabised national communities. Likewise, we often associate multilingualism with openness and subversion, but the Ottoman Empire cultivated a multilingual canon to assert a hegemonic sense of imperial superiority.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

When I submitted the book proposal and sample chapters to Edinburgh University Press, I did not think that I would write a book on ‘the construction of Arabic and Turkish literatures’; I thought that my book would be on modernity. After I read comments from the Series Advisory Board and then the two reviewers, the book shifted its focus. Many authors I study, such as Jurjī Zaydān and Ebüzziya Tevfik, claimed that their literatures entered a new era during the late Ottoman period. However, my book ultimately ended up arguing that this claim has made us accustomed to viewing Arabic and Turkish traditions as national traditions that have existed since time immemorial. Ultimately, The Ottoman Canon suggests that literary critics should not solely pay attention to modernity when they study the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

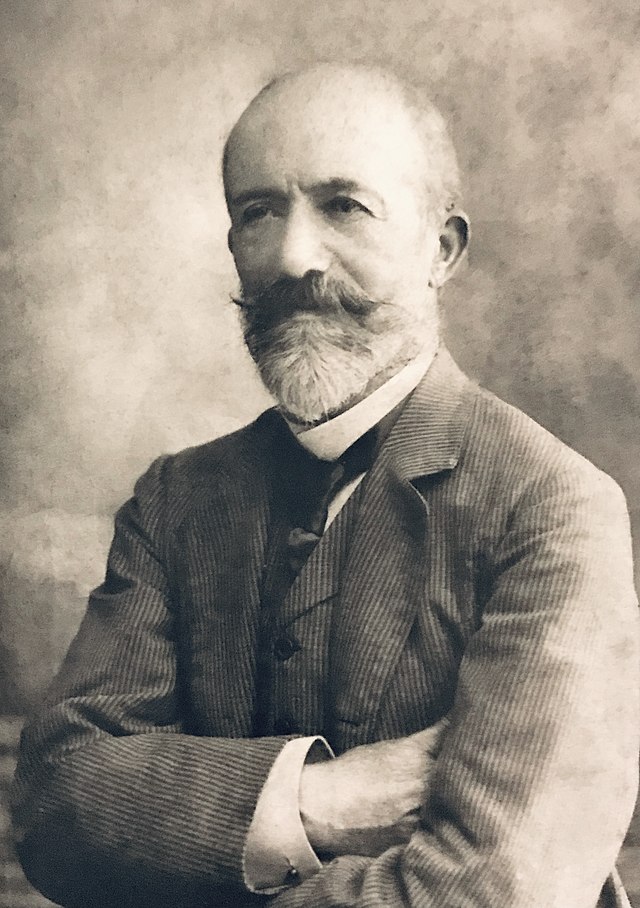

Ebüzziya Tevfik Bey, educator, intellectual and writer. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

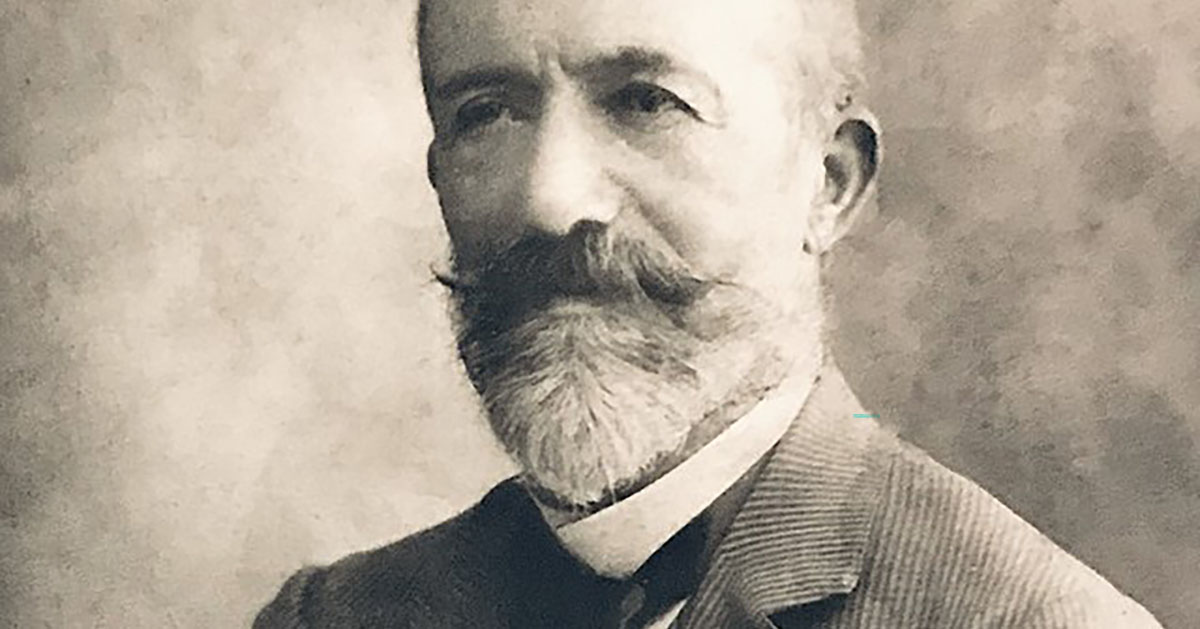

Jurjī Zaydān, the Beiruti-Egyptian scholar and journalist. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

Ottomanists love archives. The Ottoman Canon draws upon an extensive array of sources. At the same time, I wanted to use different methodologies, like close reading, that we do not see much in Ottoman Studies. Archival research can be great and sometimes even necessary; however, many scholars based in developing countries do not have the privilege to obtain visas or have the financial resources to allow them to travel. I wanted these scholars to believe that they can generate original research even if they do not have access to rare sources. They can still come up with original interpretations and theories on sources that specialists know inside out.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Ceyhun writing, accompanied by a feline visitor. Author’s photograph (2023)

I now see my life as part of the larger story of the Middle East. The Ottoman Canon lays out the ‘mental manoeuvres’ – comparisons, definitions and reassessments – that late Ottoman authors made to lay the foundation of communal identities in the region. No one in the Middle East should feel that they do not belong due to their lifestyle or worldview because no one is absolutely ‘authentic’. The region’s communal identities result partly from the manifold mental manoeuvres that my book examines.

What’s next for you?

I am currently working on a second book project tentatively entitled Becoming Mediterranean: Views from Arabic, French and Ottoman Literatures.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases

About the book

Get 30% off your copy with code NEW30

The Ottoman Canon and the Construction of Arabic and Turkish Literatures studies the intertwined manner in which Arabic and Turkish literatures took shape as national traditions. It fleshes out the Ottoman canon’s multilingual character to call for a literary history that can reassess and even move beyond categories that many critics take for granted.

About the author

C. Ceyhun Arslan is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Koç University. His articles and book chapters have appeared in journals and edited volumes such as Journal of Mediterranean Studies, Journal of Arabic Literature, and The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Poetry and Sea of Literatures: Towards a Theory of Mediterranean Literature. He has recently been awarded a Georg Forster Fellowship for Experienced Researchers from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.