by Tim Snelson, William R. Macauley and David A. Kirby

In the ‘long 1960s’, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals intervened in and influenced cinema culture in unprecedented ways, changing how films were conceived, produced, censored, exhibited and received by audiences. This blog draws on the findings of our book, Demons of the Mind: Psychiatry and Cinema in the Long 1960s, presenting psychiatric films that made significant interventions at the intersection of the fields of mental health and media.

The Three Faces of Eve (1957)

Nunnally Johnson‘s The Three Faces of Eve has a foot in two eras. It marks the culmination of the classical Hollywood ‘psychiatric picture’, with its Godlike clinician hero (think Johnson’s 1946 film The Dark Mirror), and the start of a new era of psychiatric realism, when filmmakers sought to depict mental health conditions more accurately.

An adaptation of a real case history of a woman diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (then multiple personality), Eve celebrates the doctors’ therapeutic interventions but also seeks to authentically detail it’s titular character’s experiences. Joanne Woodward studied hours of documentary footage of the real ‘Eve’, Christine Costner Sizemore, as she shifted between alters (alternative identities). As a result, Woodward won an Oscar for her performance.

However as our book shows, underlying both the original case history and the production processes of the film, were attempts to write out some of the complicated and contradictory aspects of Costner Sizemore’s story that did not fit a neat narrative of ‘cathartic cure’. This included both psychiatrists and filmmakers denying the return of her condition during (perhaps resultant of) the making of the film.

Psycho (1960)

In considering the relationships between psychiatry and cinema, especially around the 1960s, it’s hard to avoid Psycho. Alfred Hitchcock’s film has been hailed as pioneering in its use of the cinematic apparatus to allow the spectator to experience, even empathise with protagonist Norman Bates’ psychotic episodes. Alternately, it has been decried for establishing a troubling link between certain dissociative mental health conditions and violent behaviour.

The film’s success inspired an Anglo-American cycle of ‘Psycho’ pictures, some prestige productions made by auteurs like William Wyler and Otto Preminger, others quickly-produced Hammer horror films like Maniac (1963) and Paranoiac (1963).

Some of the filmmakers we studied devised their movies as antidotes to Psycho, however, seeking to tell more complex stories about the relationships between childhood trauma and violent crime. This included Hollywood director Richard Brooks, who saw the psychological aspects of Hitchcock’s film as superficial and ‘poorly done’. For his adaptation of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966), Brooks allied with a number of leading psychiatrists from The Menninger Clinic, who shared his opinion that criminality should be understood and treated as mental illness. Together they introduced a controversial anti-punishment agenda into In Cold Blood (1967), which angered author Capote.

Freud (1962)

Despite Sigmund Freud‘s disdain for cinema, he had a huge influence on Hollywood storytelling. In telling the origin story of the ‘father of psychoanalysis’, veteran director John Huston sought to move beyond these well-established cinematic conventions. Huston’s Freud is not a conventional biopic. It is an adaptation of Freud’s Studies on Hysteria (1895) and account of the discoveries that led to the book.

Huston sought to ‘evolve a whole new movie language’ for depicting psychoanalytic ideas. For dream sequences, he replaced the cliches of ‘stagey fantastic sets’ used in films like Spellbound (1945) with a ‘hard realism’ that recreated the grainy look of Orthochromatic film stock used at the time the film is set.

Freud was instrumental in shifts in American film censorship. When it was submitted to the Production Code Administration (which regulated Hollywood) it was deemed unacceptable, and therefore unreleasable, because it engaged with Freud’s ideas about infant sexuality. This showed the Code to be out-dated and unworkable. How could Freud and his long-accepted ideas be unacceptable? This prompted a shift from a religious to psychological basis for censorship decisions, later formalised in a new age-based classification system (CARA) headed up by a psychiatrist.

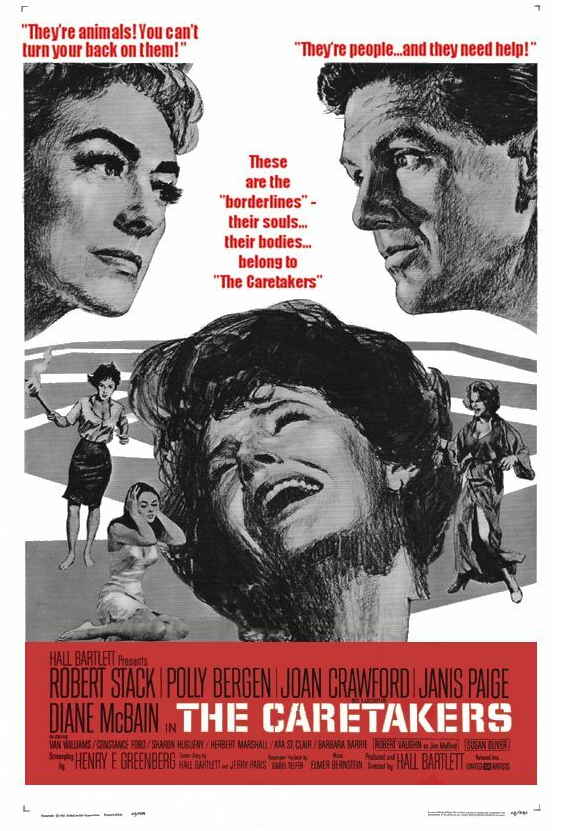

The Caretakers (1963)

The Caretakers (released in Britain as Borderlines) was important in breaking the British Board of Film Censors’ (BBFC) taboo on films set in mental hospitals. This serious Hollywood film, that advocated for psychotherapeutic methods such as group therapy, was screened in US Congress and influenced the passing of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963.

As a result, the BBFC was forced to revisit its prohibition policy and, realising it didn’t have the requisite expertise in-house, started deferring to psychiatric experts. These consultants, referred to as ‘psychiatrist friends’, moved the BBFC from a position of banning such films on the grounds that they spread dangerous misinformation, to seeing them as productive mechanisms for enhancing mental health awareness. As our book shows, this fundamental ideological shift within the Board paved the way for the challenging British films discussed below.

Family Life (1971)

For Demons of the Mind, we were fortunate to interview the late great producer Tony Garnett and director Ken Loach about their collaboration with R.D. Laing and other radical psychiatrists on the film Family Life and BBC television play In Two Minds (1967). These films brought the ‘rebel’ ideas soon be referred to as ‘anti-psychiatry’, to public awareness. These films provoked controversy and questioning of British mental health treatment and helped launch Laing’s celebrity status as ‘the Mick Jagger of psychiatrists’ in America.

We suggest that it was these films and others in our book, rather than the more well-known One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), that brought anti-psychiatry to public awareness. In fact, on release Cuckoo’s Nest was deemed a nostalgic revisiting of Sixties counterculture and anti-psychiatry rather than a topical intervention by them. For this reason, our book ends on the cusp of Cuckoo’s Nest’s production rather than seeing it as a key part of our story.

About the book

Get 30% off your copy with discount code NEW30

The first interdisciplinary account of the complex contestations and cross-pollinations of the ‘psy’ sciences (psychiatry, psychoanalysis, psychology) and cinema in Britain and America during the defining ‘long 1960s’ period of the late-1950s to early-1970s.

Don’t forget to sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases!

About the authors

Tim Snelson is associate professor in media history at the University of East Anglia. His research looking at the relationship between media and social history has been published in a number of books and journals, including Phantom Ladies: Hollywood Horror and the Home Front (2015).

William R. Macauley is a lecturer at the University of Manchester and senior research associate at the Science Museum, London. He has an academic background and extensive research experience in psychology and the history of science, technology, and medicine.

David A. Kirby is professor in science and technology studies at Cal Poly University in San Luis Obispo. His research examines how movies, television, and computer games act as vehicles of scientific communication. His other books include Lab Coats in Hollywood: Hollywood: Science, Scientists and Cinema (2013).