by Jeroen Wijnendaele

(This text incorporates my introduction for the book launch of Late Roman Italy at Hamburg’s RomanIslam centre – 21.11.2023)

Fergus Millar once claimed that “Italy under the Empire has no history.” He meant that it had no narrative history, at least for the period from Augustus to Constantine I. Millar wrote this in 1986. He was mindful of the historiographical Zeitgeist: narrative history had become deeply unfashionable. Instead, scholars ought to be working on social history or the longue durée like the Annales school, of whom its then-leader Fernand Braudel had just passed away. This is the time when, just months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Francis Fukuyama would declare we were heading towards the end of History. If anything, our current century shows we do not lack history. The same is true for Late Roman Italy.

Italy from the crisis of the third century to Gothic rule brims with history. It’s easily the best documented western Roman region both in literary and material sources. This was already noted in seminal works such as Thomas Hodgkin’s Italy and its Invaders (1890s) or Lellia Cracco Ruggini’s Italia Annonaria (1961). But for many historians Italy is usually just a landscape where other histories are played out, rather than its own focus of analysis. Together with 18 colleagues from 9 different countries, we set this straight. This diversity is crucial because as a Roman region, Italy has been studied by various schools of thought, each with their own traditions and idiosyncrasies. Ironically, while recent decades have seen an international surge of Late Antique studies, research results still do not transfer equally among Anglophone, French, German or Italian schools. I would like to elaborate now on three editorial choices.

1. Periodization

I deliberately used the unconventional era 250-500 CE to study Italy. This was partly pragmatic. Gothic Italy, especially Theoderic’s reign, is well covered as seen recently by Jon Arnold, Marco Cristini or Hans Ulrich Wiemer’s studies. There’s also the excellent Brill Companion to Ostrogothic Italy by Tina Sessa and her colleagues. And despite Millar’s caveat, there are now ample studies of Italy during the Principate. Yet nothing illustrates better the need of this volume, like The Blackwell Companion to Roman Italy, where out of 25 chapters the entire period of 300-550 is relegated to a single chapter. Within these termini of 250-500, there’s a whirlwind of history that Millar found so conspicuously absent earlier.

During the first quarter of the first millennium, Italy was still the heart of the Roman Empire; the only political superstructure ever managing to encompass the entire Mediterranean world and its European hinterland. Yet during the second quarter of this millennium, Italy underwent dramatic evolutions from provincial demotion in the late third century, to being a new imperial hub kept afloat by cannibalizing other provinces’ resources at the end of the fourth century, to an autonomous regnum governed by non-Roman rulers as part of an Eastern Roman ‘Commonwealth’ in the late fifth century.

2. Conceptualization

This is a volume about Late Roman Italy, not Late Antique Italy. The difference matters. Already in 1999, Andrea Giardina made critical remarks about the Esplosione di tardoantico (‘Late Antique Boom’). Certainly, Late Antiquity is a paradigm that has tremendously advanced our field since the pioneering work of scholars like Alois Riegl, Henri Pirenne or Peter Brown. But the field of Late Antiquity is one that traditionally favours East over West, cultural and religious studies over secular ones, and has a much more positive outlook on its society. As any discipline, it makes intellectual choices which have consequences.

Bryan Ward-Perkins once joked that the Late Antiquity Guide (Bowersock, Brown & Gabar 1999) has no entry for ‘Praetorian Prefect’ – the most powerful civilian office of this era. But you can find entries on ‘Prayer’ and ‘Pornography’. Here I sympathize with Millar and historiographical vogues. It’s not as fashionable to study the Late Roman Empire as it is to study Late Antiquity. And yet they’re not the same. This is especially true for Italy that c. 500 is still recognizably Roman, because it retained more imperial infrastructure than any other western region. Especially the praetorian prefecture was key for Italy’s resilience in this period. Arnaldo Momigliano was bang on with his verdict on 476 as la caduta senza rumore di un impero (“The fall of an Empire without noise”).

But let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. Rather than obsessing over ‘Continuity’, ‘Decline’ or ‘Transformation’, focusing on a single region in an a-typical periodization can help us re-considering these frameworks. New trends do help advancing our field. That’s why readers can find chapters on environmental history, agrarian history-from-below, gender, or religious minorities.

3. Italy. Not Rome.

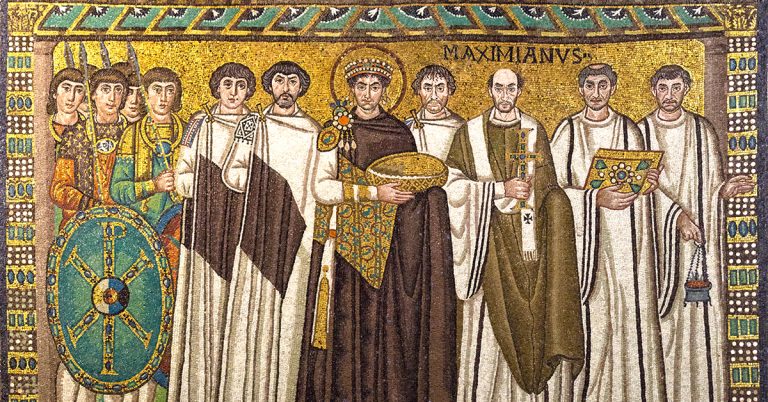

Besides Gothic rule, the city of Rome is easily the best studied aspect of Italy in this period. Recently we’ve had excellent works by colleagues such as Carlos Machado, Fabrizio Oppedisano and Michele Salzman. True, sometimes we cannot escape Rome’s shadow – especially culturally. But the majority of this volume considers the whole of Italy, from the peninsula, to Sicily, Sardinia, Corisca and even Raetia – an integral part for most of this period. More importantly, it is then that we see the fundamental division between northern Italy (Italia Annonaria) and the central-south (Suburbicaria) occurring, which still lingers today. Yet at the very end we even catch glimpses of a project coming into fruition yet ultimately undone by Justinian: a unified Italia.

About the book

Explores the major political, social, economic, religious and cultural changes impacting what was once the most important region of the Roman world

For more about one of the most fundamental transformations in Late Antiquity, see Jeroen W.P. Wijnendaele’s book Late Roman Italy: Imperium to Regnum, out now to buy in hardback and ebook.

Don’t forget to sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with all of our free content and latest releases!

About the author

Dr. Jeroen W.P. Wijnendaele is a Senior Fellow of the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies. He is the author of The Last of the Romans. Bonifatius, warlord and comes Africae (Bloomsbury Academic 2015), and has published various articles and book-chapters on the political and military history of the Late Roman Empire. Dr. Wijnendaele was guest-editor of the Journal of Late Antiquity’s 2019 theme-issue on ‘Warfare and Food-Supply in the Late Roman Empire’. At the moment, he is preparing a new monograph on Rome’s Disintegration. Violence, War, and the End of Empire in the West for Oxford University Press.