by Tim Thornton

The Princes in the Tower

The discovery of King Richard III’s body under a Leicester carpark in 2012 revitalised the public’s attention to one of the most controversial figures in British history, and to the mysteries surrounding him. As I write this blog, the trailer for The Lost King, directed by Steven Frears and staring Steve Coogan, has launched ahead of the film’s release in October 2022.

The Princes in the Tower (1878)

John Everett Millais

Source: allart

Much of the fascination surrounding Richard’s reign revolves around the disappearance of Richard’s nephews, King Edward V and his brother Richard, the Duke of York, during 1483, after being denounced as bastards and displaced from succession.

Worldwide fascination evoked by Richard III and the mystery of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ continues to grow. And at the heart of that mystery, lies the account written by much-celebrated lawyer, philosopher, politician and Roman Catholic saint, Sir Thomas More.

More was the first person to allocate specific responsibility for the disappearance – and death – of the two princes. In his History of King Richard III, written three decades after Richard’s dramatic coup, More identified Sir James Tyrell as primarily responsible, along with two servants, Miles Forest and John Dighton.

However, More’s account of Richard and the ‘Princes in the Tower’ has been met with scepticism over the past century and a half. Whether it has been characterised as ‘Tudor propaganda’, written for a hostile new dynasty to blacken the name of the king they overthrew, or treated as no more than an abstract exercise in political philosophy, few have responded to the evidence and challenges it offers as narrative history.

Yet that opportunity clearly exists.

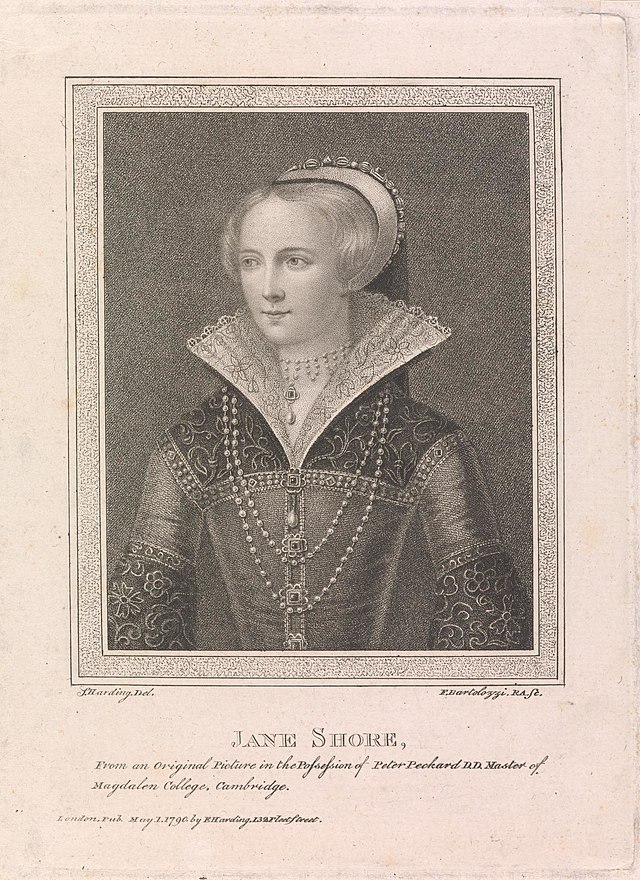

Jane Shore and the world of Thomas More

One of the things for which More’s History of King Richard III is remarkable is his vivid portrayal of a range of other characters who he says were central to the crisis of 1483. This is perhaps most pronounced in the case of ‘Jane’ Shore, the mistress of the princes’ father, the recently dead Edward IV. More’s account of Shore (whose name was in fact Elizabeth) is famous for its sympathetic response to a figure who conventional contemporary morality would suggest he should have scorned. Yet, for those same reasons which lead many readers to scepticism about other aspects of More’s history, some have discounted the descriptions of Shore as purely a literary or philosophical device – to the extent that her relationship with the king itself has been called into question.

My article in this summer’s Moreana explores the evidence available to More as he wrote his History, emphasizing the near-complete absence of Jane Shore from earlier chronicles and narratives on which he might have drawn. Shore was very much a novelty in More’s account. I have reconstructed Shore’s activity in the 1470s and 1480s, and most importantly considered evidence for Shore and her husband Thomas Lynom’s survival into the 1510s when More was writing. The evidence highlights the degree to which their activities and circle intersected with the environment in which More was shaping the History. As a central figure in the events of 1483 who survived into the 1520s, Shore was a prompt to the creation of More’s account – she was not simply a product of More’s literary and philosophical imagination, but part of his effort to respond to the immediate legacies of conflict in politics and society.

This article therefore builds on my 2021 article in History (‘More on a Murder: The Deaths of the “Princes in the Tower”, and Historiographical Implications for the Reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII’) in suggesting that many of those More wrote about, or their close family, were part of the world in which More lived and worked in London and around the court. This includes the sons of one of the alleged murderers of the princes, Miles Forest, who were servants of the king and of Thomas Wolsey. More’s history was therefore an essay in creating contemporary history in the aftermath of a brutal civil conflict, which explains both its brilliance and the difficulties he faced with completing and publishing the work.

My article in Moreana therefore sheds further light on the first decades of the development of More’s account, with implications for his writing of history and the nature of the contemporary ‘Tudor’ regime. More’s Richard III is not just a great work of political philosophy, but also a narrative constructed by an author who had access to men and women whose witness takes us very close indeed to the dramatic events of 1483.

About the journal

Moreana publishes academic research about the person, historical milieu, and writing of the English humanist, Thomas More. In addition, the journal promotes research in cultural, historical, religious, and political contexts of the sixteenth-century Rennaissance period.

Find out how to subscribe to Moreana, recommend to your library, sign up for Table of Contents alerts, and submit a paper.

Want to keep up with all of the latest content from Edinburgh University Press? Sign up for our newsletter!

About the author

Tim Thornton is Professor of History and Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the University of Huddersfield. Tim works on the late medieval and early modern political and social history of the British Isles, spanning the period c. 1400-1650. Tim studied at New College, Oxford, where he was awarded a first in Modern History and later completed his DPhil, under the supervision of Christopher Haigh. In 1997 Tim was awarded the Royal Historical Society’s David Berry Prize for his work on the Isle of Man; in 1999 he was proxime accessit for the Society’s Alexander Prize for an essay on the palatinate of Durham. He was the first scholar based in a new university to win one of the Society’s prizes. His books include Cheshire and the Tudor State, 1480-1560 (2000), Prophecy, Politics and the People in Early Modern England (2006), The Channel Island, 1370 – 1640: Between England and Normandy (2012), and, with Katharine Carlton, The Gentleman’s Mistress: Illegitimate Relationships and Children, 1450–1640 (2019). His work on Thomas More, Richard III and the ‘princes in the Tower’ featured in an episode of Lucy Worsley Investigates (BBC Studios / BBC 2) in 2022.