by Walter Feldman

Love is the Way and the Path of our Prophet.

We are Love’s children, and Love is our Mother.

Rumi

These words echo down through the ages from when Mevlana (”Our Master”) Jalaluddin Rumi (d. 1273), first wrote them, in the thirteenth century, to the lyrics of the Dügah Mevlevi ceremony in the later sixteenth century, and until our own day.

Mevlevi Dervishes – A Community Based on Love?

Rumi has been much treasured as a Sufi poet throughout the Persian-reading world, from Bukhara and Khorasan, to India and Iran itself. But today it is less widely appreciated that Rumi’s spiritual and cultural legacy had no institutional basis in any of these countries. It had such a basis only in Anatolia under the Turkish Seljuq and Karamanid dynasties, and then in the core territories of the Ottoman Empire. This basis was the Mevlevi Order of Dervishes, founded by Rumi’s son Sultan Veled (d. 1312). The goal of the Mevlevis was to build a community based on love. But how to transform individual members of that community so that they could maintain this love in all of life’s situations?

The ceremony of the Mevlevi dervishes, known as ayin, mukabele and sema, claims our attention because it is a ritual whose combination of choreographed movement and complex music achieves a result that is both transcendental and artistic. That this ceremony is regarded as a major cultural phenomenon in our own time speaks to the enduring success of those who had maintained it, over centuries, as part of a mystical, rather than a purely religious institution. Among many other practices, the sema, with its music, movement and poetry is one important technique that the Mevlevis developed with this transformative aim.

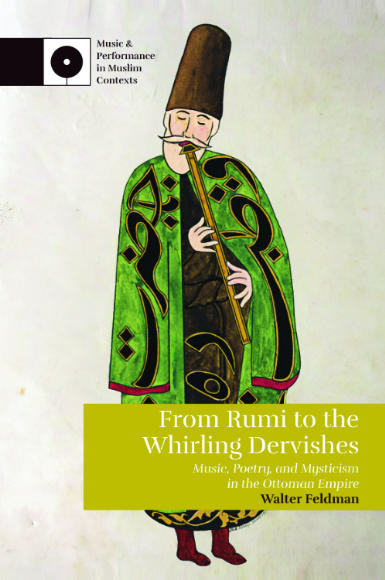

From Rumi to the Whirling Dervishes is the first book in any language that attempts to integrate the musical, mystical and poetic creations of the followers of Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi, from their inception until modern times.

The Spiritual Legacy of Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi

The Mevlevi ceremony has elicited wonder since European travelers first viewed it in Istanbul in the early seventeenth century. Travelers’ descriptions, as well as European paintings of the ceremony, furnish some of its earliest documentation. Meanwhile, Jalaluddin Rumi, whose lyrical Persian poetry has furnished the core “libretto” for all classic ayin compositions, is nowadays widely billed as “the best-selling poet in the United States.” He is also known worldwide through translations into many European and other languages. In addition to its technical excellence, the ayin constitutes a vision of the human’s role in the universe. Its felicitous union of music, poetry, and philosophy is of major interest to humanity in general and represents possibly the most significant contribution of the Turkish nation to our shared civilization.

Within this whole complex, human artistic creation held a highly significant role. There is no way to follow the history of artistic music in either pre-Ottoman or Ottoman Turkey without understanding the role of the Mevlevis. The talents of the leading Mevlevi musicians were not confined to the ritual music of the sema ceremony alone. These dervish musicians were able to distinguish a mystical use and structure of music from the secular styles that had developed in a courtly environment, and they were active in both of them.

The Music of the Mevlevis

Mevlevis were outstanding performers of the dervish reed-flute ney, but they also played other courtly instruments, and were known as composers and teachers of music. Among their students were dervishes, spiritual “followers” (muhibb), Christian and Jewish cantors, as well as secular musicians from all religious communities. From the beginning until the end of the Ottoman Empire, they were also active as musical theorists. They were the first segment within Ottoman Muslim society to favor the use of an indigenous, Islamic musical notation, for selected purposes. Especially during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Mevlevis were able to influence the development of both poetry and artistic music in the Sufi and in the courtly environments. Musical talent—as well as religious knowledge, poetic ability, and personal charisma—were all considered in the choice of a new Mevlevi leader, or sheikh.

During the fifteenth and sixtenth centuries the originally spontaneous and ecstatic dance-like movement favored by Jalaluddin Rumi became increasingly elaborate, ritualized, and filled with cosmic symbolism. Apparently beginning in the sixteenth century, Mevlevi composers created a new musical ceremony—the ayin. Their original creations were based on the rhythms of earlier Sufi dance practices from Greater Iran, as well as those of the Central Asian Turks. While using a commonly shared modal (makam) system, this mystical music differed in many respects from the secular music of the court, whether in its earlier Iranian or its later Ottoman form. From Rumi to the Whirling Dervishes demonstrates how this mystical musical structure differed from any of the secular musical forms in use either in the Persian or the Turkish cultural spheres.

About the Author

Walter Feldman is a leading scholar of both Ottoman Turkish and Jewish music. As a lifelong musician, Feldman performs on the Ottoman tanbur and the cimbal—the traditional Klezmer dulcimer. He has held teaching positions at Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and New York University Abu Dhabi. From Rumi to the Whirling Dervishes: Music, Poetry, and Mysticism in the Ottoman Empire is available now.

Keep up to date with new content in your field by joining our mailing list.

Browse more posts in Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies.