by Pål Kolstø

More than a hundred thousand Russian soldiers have marched up to the Ukrainian border and the world is waiting in trepidation: what will happen next? What is Putin up to? Is this a prelude to war? Why Ukraine? Europe is abuzz with questions and conjectures, but informed answers are rare.

A colleague of mine claimed that before the recent crisis, few of her friends would be able to point to Ukraine on a map. Well, in Russia no one is in doubt about the existence of Ukraine, and most Russians regard Ukrainians not only as their neighbours, but as their brothers. Putin is on record to have said that Russians and Ukrainians are “brotherly peoples”. And indeed, Russians and Ukrainians do have a lot in common. For centuries, they were living in the same state, first the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union; they speak closely related East Slav languages; and the majority of the people in both countries belong to the same religion, Eastern Orthodoxy.

That ought to have been be reassuring?

But Ukrainians are still jittery – and with good reason. In July last year, Putin wrote an article, which was published on the President’s official website, claiming that the Russians and the Ukrainians are not “two brothers”, but “one people”. That is a very different metaphor. If taken literally, it would mean that the Ukrainians do not exist as a separate nation at all, they are reduced to a subgroup under the larger Russian nation. And this was indeed how they were viewed under The Czars.

In the terminology of the Russian bureaucracy before the 1917 revolution, one census category was called “russkie”. “Russkie” is also what Russians are called today, but in the 19th century ethnic Russians were referred to by another name: “velikorossy”, or “Great Russians”. “Russkie” was a larger category of people encompassing not only the “russkie” but also the “belorusy” (or “White Russians”) and a third group called “malorossy”, or “Little Russians”.

The malorossy were identical with those whom we today call Ukrainians. Together, the Great Russians, the White Russians, and the Little Russians made up what was officially called “the triune Russian people”. Some Ukrainians, even those among the educated elites, accepted the term malorossy as their self-designation, and were content to fight for cultural autonomy within the Czarist state. To be sure, the names “Great Russians” and “Little Russians” reflected the differences in size between the two groups – in the late 19th century the size of the Ukrainian group was less than 40% of the Russian population, today, fewer than 30%. But, of course, these designations also expressed their respective positions in the hierarchy of the “triune” Russian people.

At times, the Czarist authorities were ready to accept manifestations of Ukrainian/Little Russian cultural identity, but as soon as they suspected that the Ukrainians might want something more, such as political autonomy or even independence, they clamped down on it. In January 1863, when Polish subjects of the Czars launched an insurrection, officials in St. Petersburg feared that the Polish rebels might be able to drag the Ukrainians over to their side. In the Czarist regime, Ukrainian-ness was widely perceived as a halfway house between Russian-ness and Polish-ness, and in order to forestall defection, it was decided that the Ukrainians would have to undergo massive Russification.

A secret decree from the Ministry of Interior in July 1863 – the so-called Valuev Circular after Minister of interior Pyotr Valuev – declared that “a separate Little Russian language has never existed, does not exist, and shall not exist. Their [Little Russian] tongue used by commoners is nothing but Russian corrupted by the influence of Poland”. Well, today, not only a separate Ukrainian language, but also an independent Ukrainian state exists – not least because the Soviet communists granted them a separate republic within the Soviet Union.

To many Ukrainians today, Vladimir Putin’s article last year was a throwback to how they were perceived and treated under the Czars. To be sure, Putin averred that “We respect the Ukrainian language and traditions. We respect Ukrainians’ desire to see their country free, safe and prosperous”. If they so desperately wanted their own state, let them have it. Putin is no latter-day Valuev. But he immediately added: “I am confident that true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia. Our spiritual, human and civilizational ties have formed over centuries and have their origins in the same sources…. for we are one people.” For Ukrainians, however, all this talk about being “one people” means that the current crisis is not only about the military security of their country, but also about their ontological security: it is a threat to their separate identity.

The Kremlin insists, in all likelihood in all sincerity, that the current crisis is not a quarrel between Russia and Ukraine at all, but a standoff between Russia and “the West”, the United States and NATO. They will not accept that NATO moves even closer to their borders than the alliance has already done. Those pundits who claim that the threat to peace today is greater than at any other time since the Cuban Crisis in 1962 may have a point. The situations are, in some respects, remarkably similar, only with the protagonists in opposite roles: in 1962, the Kennedy administration had discovered that the Soviets were sending missiles to Cuba that could reach the American mainland, and concluded that this was an intolerable threat to their security. The fact that Cuba was an independent country did not give them license to function as a potential launchpad for such an attack. Today, the Russians fear that Ukraine could become a similar springboard for attacks against their territory.

As Putin expresses it in his article, “step by step, Ukraine has been dragged into a dangerous geopolitical game aimed at turning the country into a barrier between Europe and Russia, a springboard against Russia”. He complains that “Ukraine’s ruling circles have decided to justify their country’s independence through a denial of its past….. They have begun to mythologize and rewrite history, edit out everything that unites us, and refer to the period when Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as an occupation”.

Let’s for the sake of the argument accept that there is some truth in this assertion. I have myself met Ukrainians who are indeed liable to exaggerate the cultural difference between themselves and Russians out of all proportions. But what I find difficult to understand is how Putin and his advisors fail to realize that all this talk about being “one people” is pushing Ukrainians in precisely that direction, away from them and into the embrace of the West. Not only the Russians have legitimate security concerns, so do the Ukrainians. And as long as Putin keeps harping on the common identity of the two peoples, Russian reassurances that they will respect Ukrainian independence do not sound trustworthy to them.

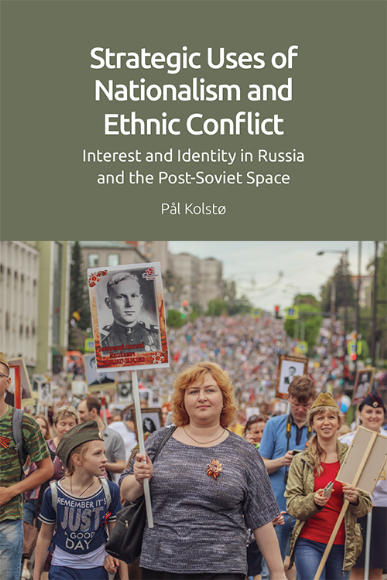

In my book, Strategic Uses of Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict: Interest and Identity in Russia and the Post-Soviet Space, (Edinburgh University press 2022) , I give many examples of how Putin has adroitly used Russian nationalism to bolster his regime. With his treatment of the Ukrainians, however, he has in my view shot himself in the foot.

More on the book (Pre-order now)

Argues that nationalism and ethnic conflict can be used as strategies to achieve power and influence

- Collects 8 thoroughly revised articles and book chapters, together with a new introductory theoretical chapter, based on Pål Kolstø’s 30 years of study of nationalism and ethnic conflict in post-Soviet states

- Uses inter-related case studies in Russia and the former Soviet Union

- Theoretically informed, with both an overarching theoretical framework and chapter-specific theoretical discussions

- Shows how the resurgence of ethnonationalism in the post-Soviet world compells us to re-examine the dynamics of ethnic conflict

- Based on specific empirical cases, drawing on a wealth of primary sources

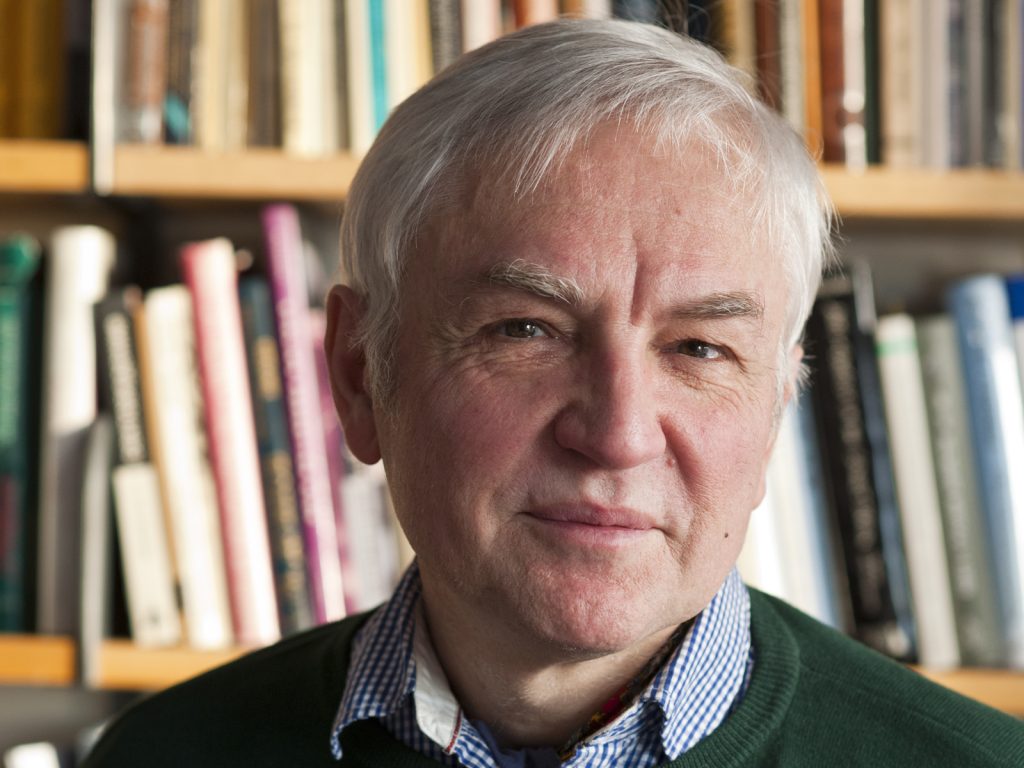

About the author

Pål Kolstø is Professor of Russian Studies at the University of Oslo. He has authored two books and a number of articles and book chapters on Russian politics, Russian history and nationalism.

Previously, he was Researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies, 1987–90, and Interpreter at the Norwegian-Soviet border, 1982-83. His main research areas are nationalism, nation-building, ethnic conflicts, nationality policy in Russia, the former Soviet Union and the Western Balkans. He has published roughly 40 articles in English-language refereed journals, in addition to numerous publications in other languages. He is the recipient of six large research grants to study nation-building and ethnic relations in the post-Soviet world and the former Eastern Europe.