by Hector L. MacQueen

David Sellar (1941-2019) was a pioneering historian of Scots law who convincingly and conclusively rejected previous interpretations of the subject as a series of false starts and rejected experiments. Instead, he emphasised the continuity of legal development in Scotland, with a change in process of integration of external influences with indigenous customs from very early times on. Thus down to the present, Scots law embraces Celtic and other customary elements reaching far back into its past, having also being open to innovation from the developing Canon, Civil, Feudal and English Common law since the Middle Ages. This too has left deep marks upon the law’s character as a “mixed legal system”.

David’s approach, articulated mainly through essays published in diverse places over four decades, has had significant influence upon the general understanding of legal history in Scotland, leading to appreciation elsewhere of its comparative significance. Gathering his major essays together in this single collection demonstrates the scope and reach of David’s overall contribution; it is perhaps an approximation to the monograph that he was not spared to write. What distinguishes the contribution from others in the field is the perspective that David himself brought to bear, which was one no other writer in the field could achieve, especially in relation to Celtic and Canon law.

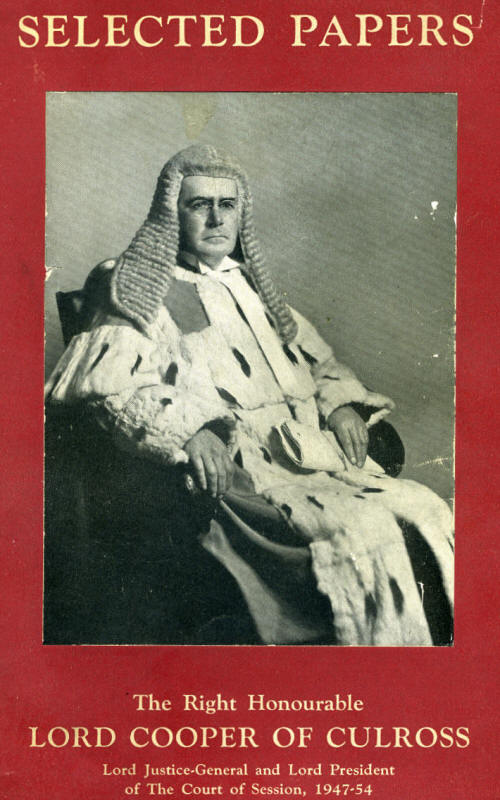

The book’s first Chapter is David’s most general treatment of Scottish legal development from the period before 1100 down to the near present. Although this essay was jointly published by the Saltire and Stair Societies in 1991, and he did much subsequent further research, it remains the best introduction to the ways in which David saw his contribution as differing from those who had gone before him, as well as providing an overview against which the subsequent chapters may be set. It originally formed part of the matter with which a Saltire Society pamphlet on the Scottish Legal System, written in 1949 by Lord President Cooper (1892-1955), was updated. Cooper’s writings in the 1940s had established the prevailing orthodoxy on the general development of Scots law from the Middle Ages on when David began his own researches at the end of the 1960s.

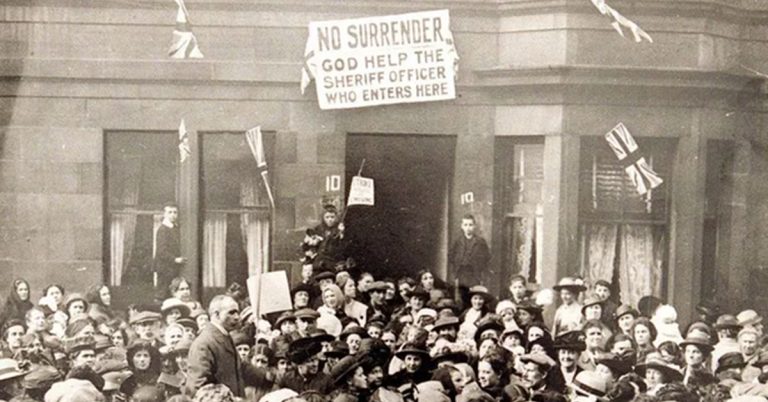

Cooper’s reiterated view was that the story of Scots law was one of “false starts and rejected experiments”, ending only with the 1681 publication of the seminal Institutions of James Dalrymple, Viscount Stair (1619-1695). The book came in the nick of time to save at least Scots private law from the fate of absorption into English law after the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. Borrowing from England had been the false start and the rejected experiment of the “Scoto-Norman” period before 1300; there had then followed a “Dark Age” for the system. From this it began to be rescued by the development of a central court (the Court of Session) in the sixteenth century, the emergence of a legal profession around that court, and (resulting in part from the education of many members of that profession in the law schools of continental Europe) a reception of the learned Roman law as taught in the universities. The end result, systematised by Stair in particular, was something quite distinct from English law, and it was expressly preserved by the Treaty and Acts of Union in 1707, along with a separate legal system within the newly united kingdom of Great Britain.

Like Cooper before him, David was most interested by the medieval period of Scots law. In part this sprang from his other central research interest, Highland and islands history and genealogy, and that clearly informed the fresh contribution that he was able to make to Scottish legal history. Where Cooper had simply passed over any Highland and islands dimension to legal development, David dug deep, not only into the Celtic law of the Highlands and the western isles, but also the Udal law of Orkney and Shetland. He was able to show that in at least some aspects these continued to form part of current Scots law and must therefore have had a continuous history despite sitting alongside the other strands of influence identified by Cooper (Chapters 1-3). A key example of an institution reaching far back into the Celtic past, dealt with in what was a posthumously published paper, was Lord Lyon King of Arms, which office David himself held with distinction from 2008 to 2014 (Chapter 4). Another example, although one that had apparently disappeared in the course of the nineteenth century, was the birlaw, where Norse influence, probably mediated through the English Danelaw rather than the northern isles, was crucial in the development of a long-lasting customary form of local dispute settlement (Chapter 5).

David agreed with Cooper in seeing the twelfth- and thirteenth-century expansion of Scottish royal justice as heavily influenced by the contemporary growth of English royal justice to become the enduring institution of the Common Law. But, helped by studies of specific topics by Harding, Barrow and others written in the decade and a half following Cooper’s death, David saw royal justice as much more significant in its own right than Cooper had allowed, and he differed from Cooper in seeing that English influence not being cut off by the Wars of Independence between 1296 and the mid-fourteenth century (see Chapters 7 and 8). The institutions of the Scottish common law such as the itinerant justiciar and the locally based sheriff established over the previous 200 years continued to operate along with the feudal structure of land law (including succession to land) which also took shape in Scotland the century after the Norman conquest of England in 1066. There was of course further development as well as continuity in these aspects of the system, with the justiciar becoming the modern Lord Justice General at the head of the High Court of Justiciary in the seventeenth century and the law’s feudal aspects being continuously adjusted and reformed until brought to an end by the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000.

David contended in 1981 that this continuing English influence could also be detected in Stair’s Institutions, in particular in the “ancient and immemorial customs” of the law of succession to land, which were derived from the Common law of Anglo-Norman England (Chapter 6). Stair had further pointed out that Scotland, like England, regarded ancient custom as its common law, “anterior to any statute and not comprehended in any, as being more solemn and sure than those are.” Also similar to English practice was Stair’s use of court decisions as recent custom and a source of law. “In a sense,” David wrote in a later contribution not included in the collection, “the story of custom as a source is the story of the common law of Scotland itself” (W D H Sellar, “Custom as a source of law”, Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia vol 22 (1987) para 355).

The theme of English influence and the customary basis of Scots law was developed even more strongly in a paper (not included in the present collection because most of its ideas were developed in greater depth in subsequent publications which have been included, notably Chapters 7, 8, 11-13: W D H Sellar, “The common law of Scotland and the common law of England”, in R R Davies (ed), The British Isles 1100–1500: Comparisons, Contrasts and Connections (1988) 82). Only in the sixteenth century had the two systems begun to move significantly apart, with the establishment of the Court of Session as a College of Justice in 1532 being a critical event in that process. David saw this as a deliberate breach in continuity with the medieval court structure, with the Session acquiring a jurisdiction in land questions it had previously lacked and in the process ensuring that, unlike England, law and equity were administered together in a powerful central court.

Head to Parts 2 and 3

About the book

Brings together 15 principal essays by David Sellar (1941–2019), reflecting his pioneering contribution to Scottish legal history

- Groups essays into topics, covering Celtic law and institutions, the influence of Canon and English law across a wide range of legal subjects (including family law, succession, criminal law, evidence) and customary law

- Includes a paper written during Sellar’s time as Lord Lyon King of Arms (2008–14) but left unpublished at his death, dealing with the history of the office of Lyon itself and arguing for its ancient Celtic origins

- Demonstrates the continuity of legal institutions in Scotland from the early middle ages on, assesses influences shaping change over time, and the processes of integration and then re-integration down to the present

- Includes a general introduction by Hector L. MacQueen assessing and contextualising Sellar’s contribution to the field

About the author

Hector MacQueen has been a member of the Edinburgh Law School since 1979. Appointed to the Chair of Private Law in 1994, he was Dean of the Law School 1999-2003, and Dean of Research and Deputy Head of the College of Humanities and Social Science in the University 2004-2008. He is currently a Scottish Law Commissioner. He is the author of many books and articles on Scots law and its historical development in comparative perspective, and of key textbooks such as The Scottish Legal System (5th edition) (2013), Unjustified Enrichment Law Basics (3rd edition) (2013), and Studying Scots Law 4th edition (2012).

Book launch

Hector MacQueen, along with The Edinburgh Centre for Private Law, will be hosting an online book launch on 18 March 2022. Sign up for a place here.