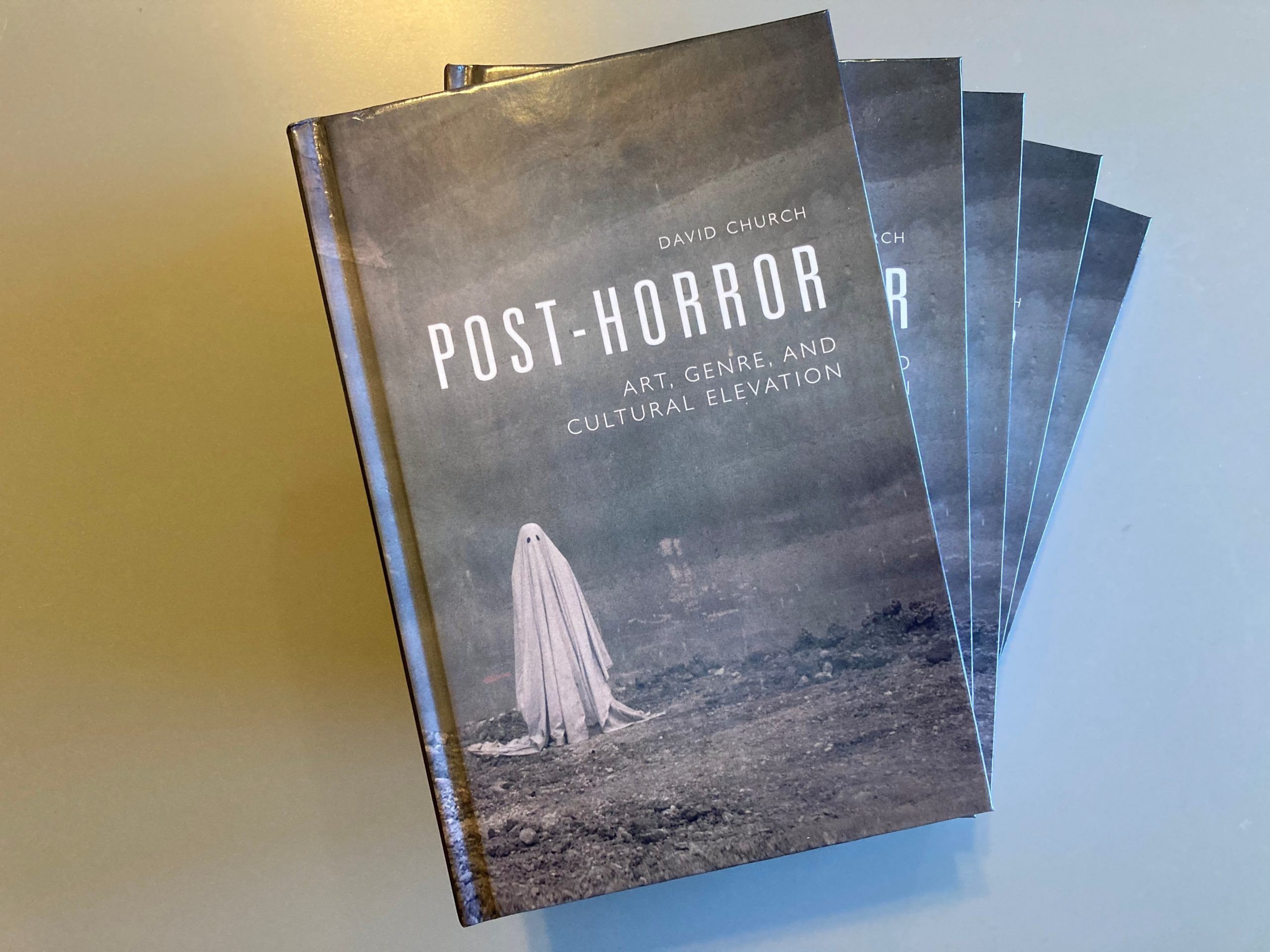

In this interview, David Church discusses Post-Horror: Art, Genre and Cultural Elevation, exploring the meaning of post-horror, its recent popularity and the films he examines in his book.

Broadly speaking, what is ‘post-horror’?

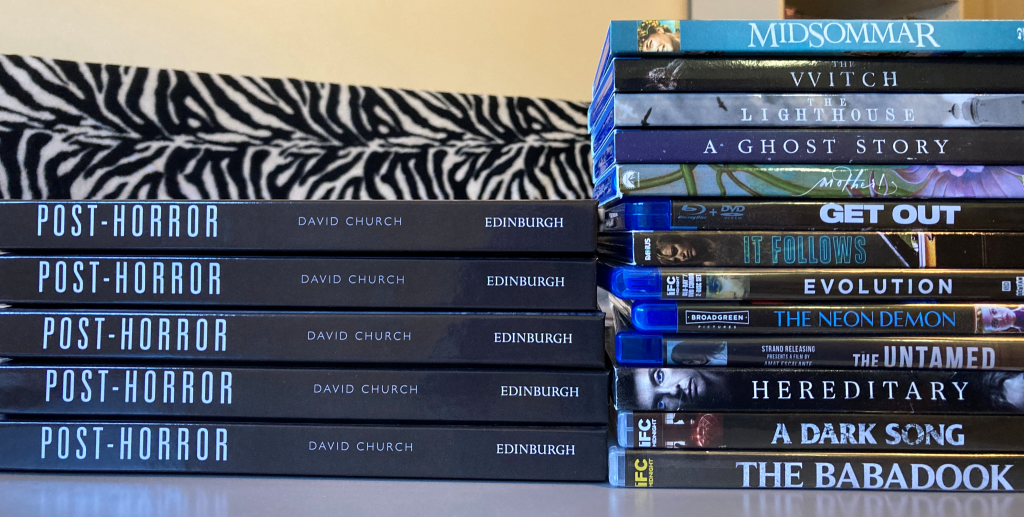

I see ‘post-horror’ or ‘elevated horror’ films (the two terms are basically interchangeable) as a new wave of films combining horror tropes with the slow pace, austere style, serious themes, and narrative ambiguity found in minimalist art films. They tend to downplay reassuringly familiar clichés and instead display a lot more stylistic restraint, forcing audiences to soak in uncomfortable moods like angst and dread. Of course, we should keep in mind the long history of overlaps between art films and horror films—including notable influences like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Don’t Look Now (1973), among others—so I see the post-horror cycle as more of an upsurge in an art-horror tradition that’s been part of the genre all along. Part of the book is about tracing those lineages that bridge between art cinema and horror cinema, complicating any straightforward assumptions about horror as a culturally ‘low’ genre.

If what these films are doing isn’t really new, why have they come such a talking point in critical circles?

One of the big differences is that a noticeable number of these films have crossed over into multiplexes and major streaming services since about 2014 or 2015, therefore getting much wider exposure than art-horror films that might have previously only reached arthouse audiences and dedicated horror fans.

Take a distributor like A24, which has made a name for itself by scouring the festival circuit for these sorts of films. High-minded critics often lavish praise on post-horror films for avoiding excessive jump scares and exploring ‘serious’ themes like grief and existential dread, rather than being seemingly average genre exercises. Meanwhile, everyday audiences sometimes feel confused or cheated when that critical buzz doesn’t translate into their idea of horror as a ‘fun’ genre.

Then again, there are a lot of hardcore horror fans who don’t seem so put off by the films themselves than the rather elitist qualifiers like ‘elevated’ or ‘prestige’ that critics have used when trying to somehow distinguish these films from the broader horror genre. Although I use terms like ‘post’ and ‘elevated’ in the book as a shorthand for this overall body of films, I share a lot of fans’ skepticism about how useful these labels really are.

You note that A24 has made a name for itself by releasing a lot of these films. How would you compare them with Blumhouse Productions, one of the other big names in horror cinema today?

Blumhouse has definitely become one of the genre’s major players over the past ten years. Even though there are some notable exceptions (such as Get Out (2017), which I discuss in the book), I generally see a lot of Blumhouse films as veering closer to more conventional horror tropes, such as paranormal hauntings and lots of jump scares. That doesn’t necessarily make their films inferior—since jump scares can be an important part of great horror movies, not just inferior schlock—but most Blumhouse films still seem inclined to deliver on the entertainment value that mainstream audiences typically expect from horror movies. After all, it’s probably no coincidence that Blumhouse has a long-term distribution deal with a major studio like Universal Pictures!

Blumhouse has also made some films (such as The Purge (2013)) that are more urgently political than a lot of post-horror films are, so there are all sorts of ways that Blumhouse has distinguished itself as an important voice in the industry, even if their ‘house style’ differs from what we might see in an A24 horror film.

Are there any films you wish you would have included in the book, but couldn’t fit in?

Yes, plenty! I’d originally planned to include analyses of The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), Evolution (2015), Under the Shadow (2016), The Eyes of My Mother (2016), The Untamed (2016), The Neon Demon (2016), and Suspiria (2018)—all of which I thought were really fascinating in their own way. But as the chapters evolved, a bunch of films had to fall by the wayside. Then, when the pandemic shuttered theaters in early 2020, I took it as a sign from the universe that it was time to draw a line in the sand and stick with the films that were available by that point. That meant, for example, I didn’t get to write something about gendered fears of aging/caretaking in Saint Maud (2019), Amulet (2020), Relic (2020), and She Dies Tomorrow (2020)—all of which were made by women.

With a few notable exceptions (Veronika Franz, Jennifer Kent, Karyn Kusama, and Jordan Peele), nearly all the films I discuss were made by white men, so there is more work to be done on how post-horror has become an important site of creativity for underrepresented filmmakers (among many other directions for future research). It would be cool if folks someday see Post-Horror as a sort of ‘first word’ on the topic, but I hardly expect it to be the last word!

About the Author

David Church is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender Studies at Indiana University. In addition to Post-Horror, he is the author of Grindhouse Nostalgia: Memory, Home Video, and Exploitation Film Fandom (Edinburgh University Press, 2015), Disposable Passions: Vintage Pornography and the Material Legacies of Adult Cinema (Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), and Mortal Kombat: Games of Death (University of Michigan Press, 2022).