By Li-Chuan TAI

In 1869, when French Lazarist Father Armand David (1826–1900) “discovered” the giant panda in Moupin, Sichuan province of Southwest China, no other Westerners had ever encountered one, and even Chinese people outside of the area had very limited knowledge of the animal or its habitat. By the 1870s, the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris could pride itself on having the richest collection of giant panda specimens in the world — all four of which had been collected and sent back to the museum by Father David himself. About fifty years later, there were still only a few museums in the world possessing specimens of this strange mammal. Besides those in Paris, there were two in the British Museum, one in the Royal Scottish Museum, one in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, two in the Berlin Museum, and two skins and skulls in the Zikawei Museum, a French Jesuit-run museum located in Shanghai.

Then, in 1928–1929, this would all begin to change when two of former US President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt’s sons, Theodore and Kermit, led the Kelly–Roosevelts Asiatic Expedition for the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, in which they shot a giant panda and shipped its carcass back to the museum. The Field Museum’s actions led many natural history museums in the US to follow suit, and the wave of hunting that ensued caused the already rare giant pandas to face the threat of extinction.

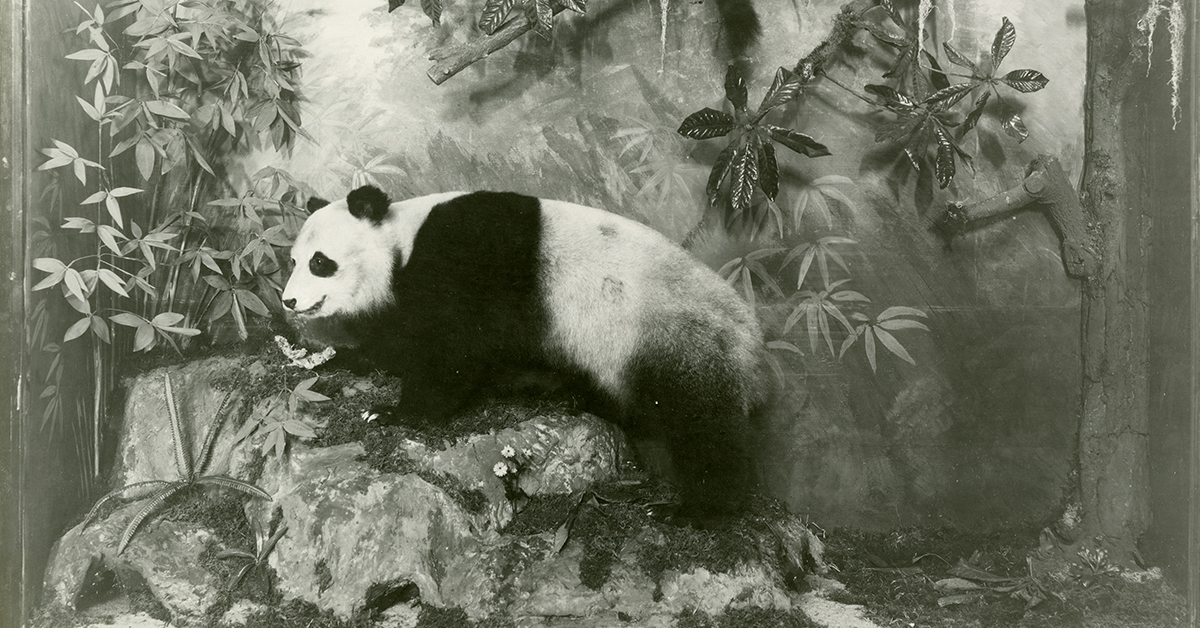

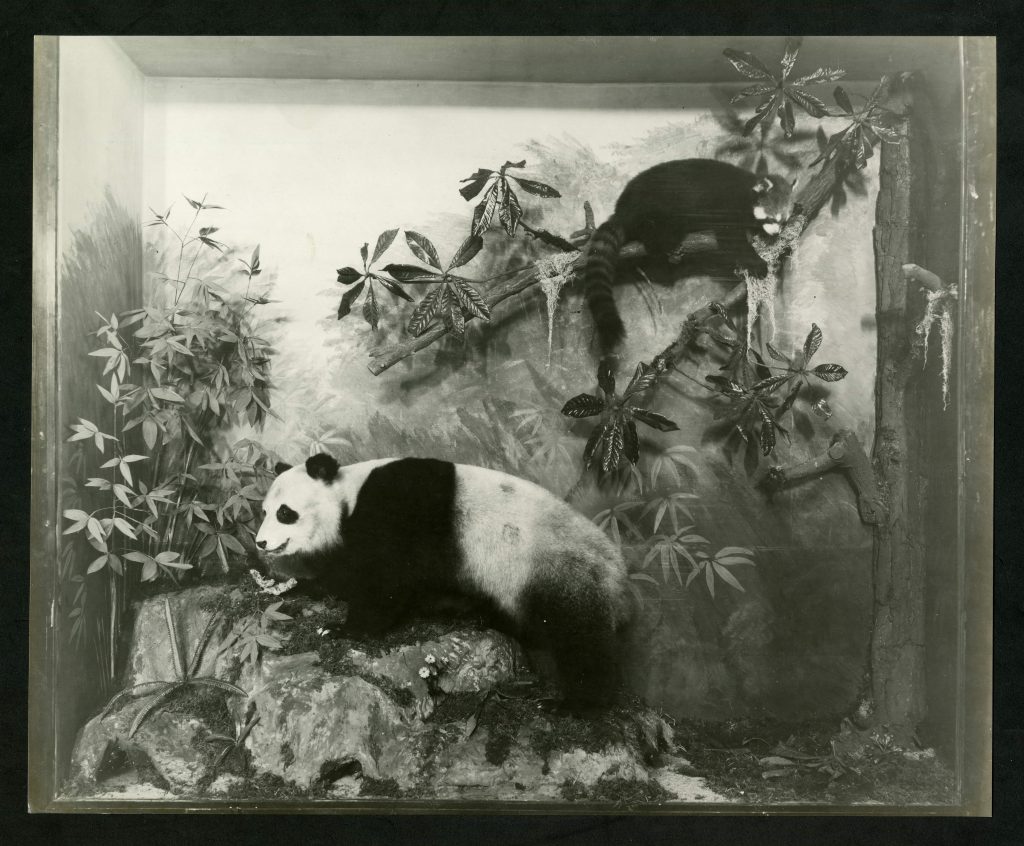

While the world became more curious about this rare animal, one museum in Shanghai was able to present a habitat diorama featuring the giant panda and another smaller species of panda together in 1933. That was the Shanghai Museum (RAS), founded in 1874 by the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (NCBRAS) and then renovated and curated by Arthur de Carle Sowerby (1885–1954), who was born in northern China into a family of British naturalist missionaries. His father Arthur Sowerby (1857–1934) had served as a Baptist minister in China for over forty years and was, for a while, the personal tutor to the son of Yuan Shikai, the influential Chinese general that rose to power during the transition from Qing Dynasty to Republican China. His great-grandfather James de Carle Sowerby (1787–1871) was one of the founders of the Royal Botanic Society in the UK, and his great-great-grandfather James Sowerby (1757–1822), a pioneer in the field of botany renowned for his illustrations in botanical and mineral atlases.

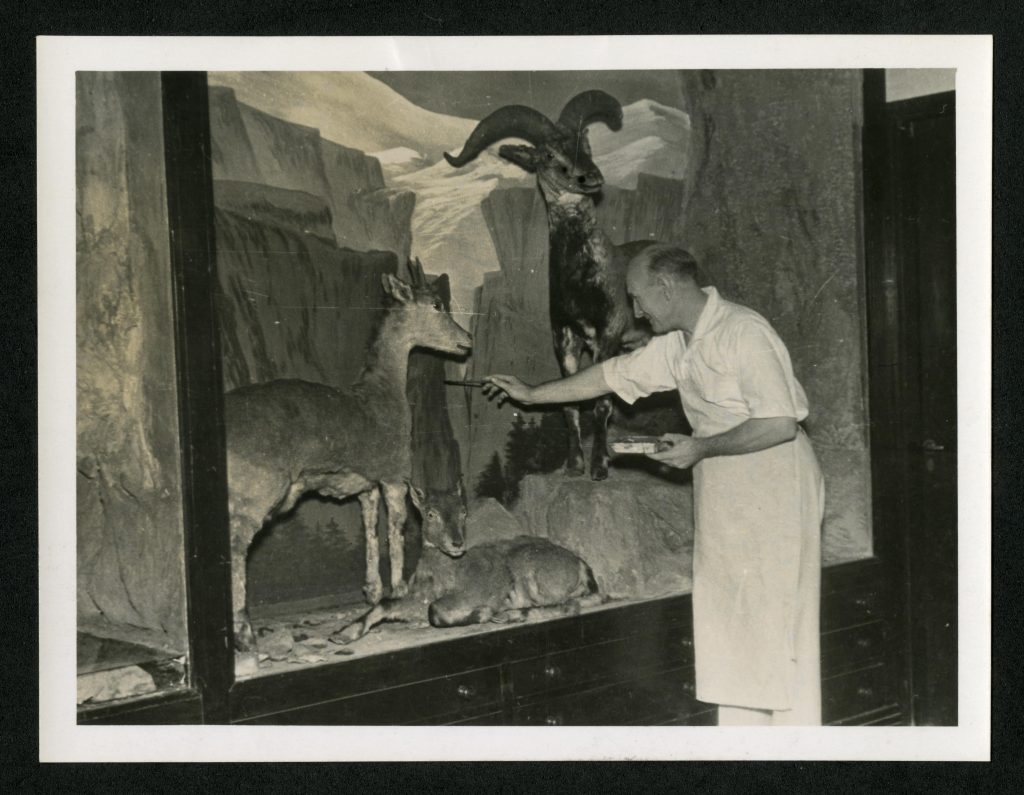

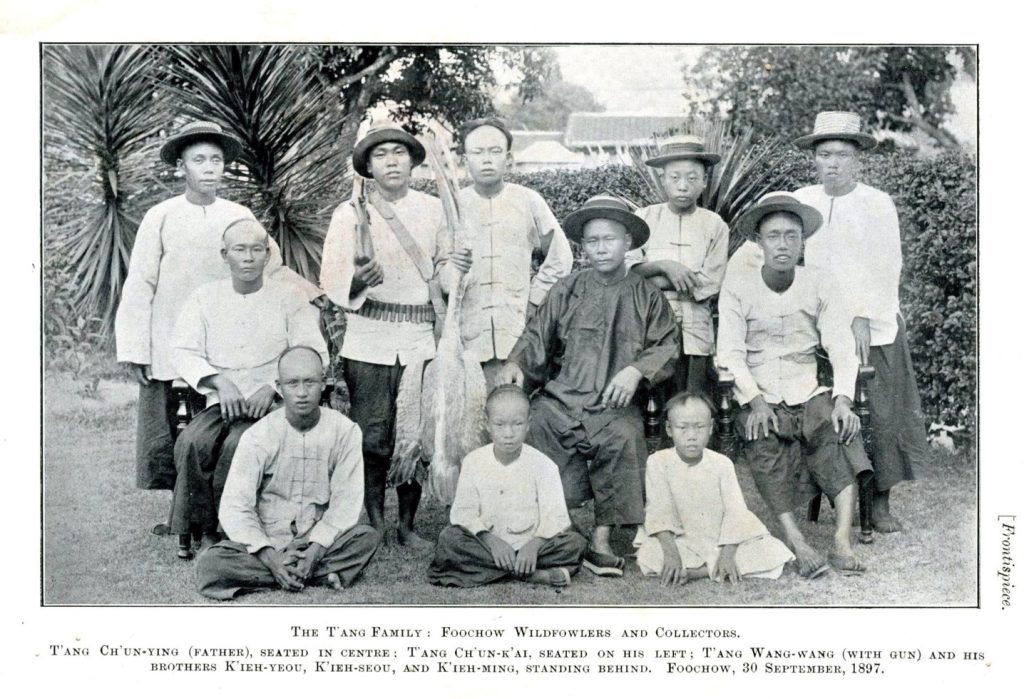

This giant panda habitat diorama was prepared by Sowerby and some Chinese taxidermists of the Tang family trained by Sowerby and, before him, by the fellow naturalist John David Digues La Touche (1861–1935), who would later be part of a long line of Chinese taxidermists. By using habitat dioramas to raise public awareness about environmental issues, the museum synchronized its work with the most innovative display methods of contemporary North American museums and offered both Chinese and foreign residents insight into biodiversity and habitat destruction in the local Chinese context.

With the giant panda and a series of new habitat dioramas, the Shanghai Museum (RAS) became even more interested in its civic education function, and it grew increasingly involved in promoting environmental conservation. For example, having observed the devastation wrought by hunting expeditions led by Westerners in China, Sowerby began to urge the Chinese government to enact legislation regulating the hunting and export of giant pandas.

Besides the exhibitions and popular science activities, the museum also served as the training grounds for Chinese taxidermists and was the first to introduce taxidermy techniques in a consistent way into China. The third generation of Tang family taxidermists working for that museum in the 1930s excelled at their trade, generating revenue for the museum and producing specimens sold to museums, institutions, and schools around the country.

After the departure of most of the foreign population by 1952 due to the communist Chinese government’s policies, the Shanghai Museum was forced to shut down. However, related techniques continued to be passed down through the Tang family’s descendants within local Chinese scientific institutions and became a form of localized knowledge and skill transfer. The local successor to the Shanghai Museum (RAS), the Shanghai Museum of Natural History, was opened in 1956, and most of the taxidermists that had worked there continued to work at the new museum until its closure in 2014. The many specimens made by members of the Tang family were then moved to the brand new museum inaugurated in 2015 in Jing’an District, which is now one of the largest natural history museums in China. Through these specimens, the legacy of the Shanghai Museum (RAS) still lives on.

For more about the Shanghai Museum, habitat dioramas, and environmental awareness in China, see The Shanghai Museum and the introduction of taxidermy and habitat dioramas into China, 1874–1952 from Archives of Natural History, Volume 48, Issue 1.

Today, most of Sowerby’s personal archives are preserved at the Smithsonian Institution Archives, where archivists, especially Tad Bennicoff, were very helpful while conducting research for this article.

Li-Chuan TAI is a Research Fellow at the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, which she joined in 2002 after receiving her PhD from EHESS, France. Her current research focuses on the earliest museums in China and the history of transnational scientific knowledge exchanges.

Archives of Natural History is the journal of the Society for the History of Natural History, providing an avenue for the publication of research on the history and bibliography of natural history in its broadest sense. Published since 1943, articles cover topics such as botany, general biology, geology, palaeontology and zoology, the lives and work of naturalists and the institutions and societies to which they belong. Find out how to subscribe to the journal and/or become a member of the Society, or recommend to your library.