By Sara Peterson

In recent years, the cultivation of opium poppies in Afghanistan has become a news item, with reports from the United Nations and the United States Government documenting record highs (no pun intended) in opium production. Now we have evidence that the association of Afghanistan with opium has resonances deep in the country’s history.

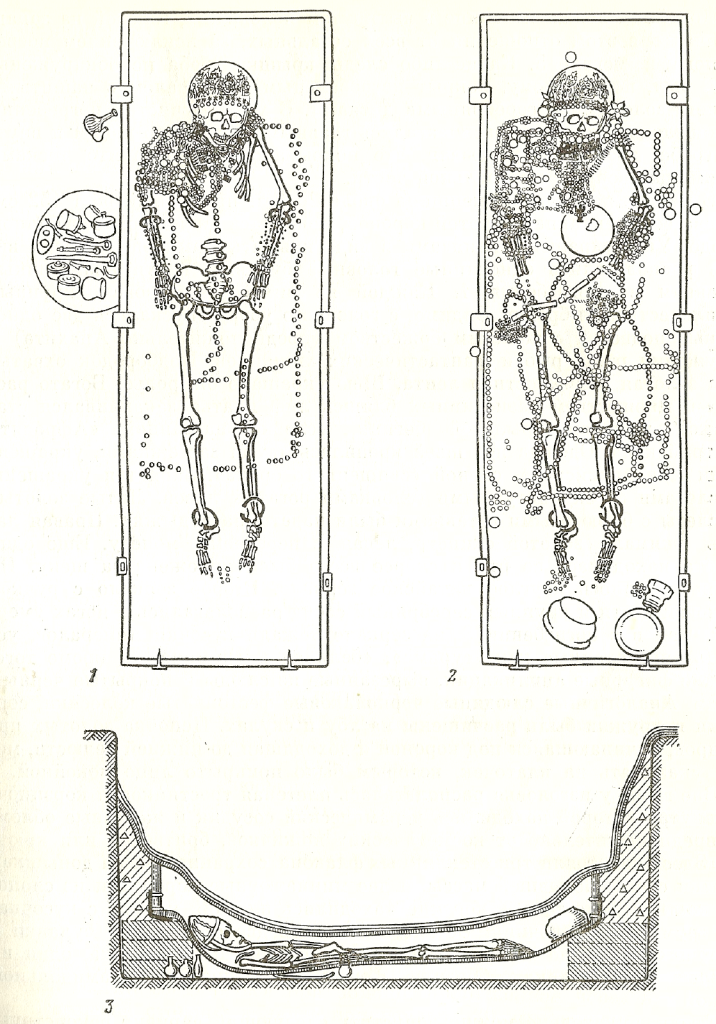

In 1978, the Russian archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi excavated six spectacular burials dating to the 1st century AD at Tillya-tepe in northern Afghanistan. One grave contained a man who was interred with the paraphernalia of a mounted warrior, including weaponry and the foreparts of a horse; while five other graves each contained the body of a richly-dressed woman. Four of these women wore copious gold jewellery, and their clothing was covered with thousands of appliqués; while a fifth, younger female was accompanied by far fewer possessions. At this time, northern Afghanistan occupied a pivotal position on the so-called ‘Silk Roads’, and the fruits of long-distance trade associated with these routes is reflected in the Tillya-tepe grave-goods, which included: Chinese mirrors, an Indian ivory comb, a Roman coin from emperor Tiberius’s reign, and jewellery decorated with imagery appropriated from the Graeco-Roman art.

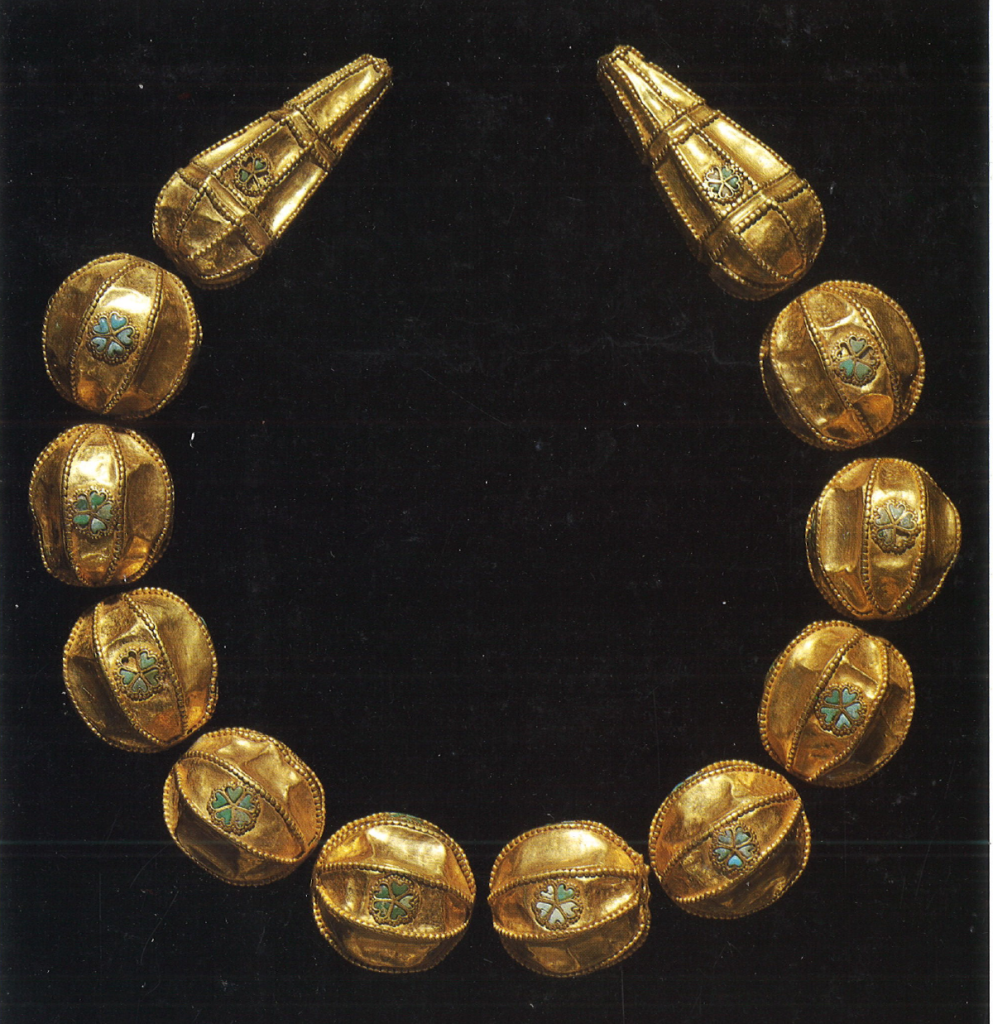

The most important of these Tillya-tepe women was buried wearing an elaborate gold floral crown and holding a sceptre. Around her neck was a heavy gold necklace, its ten substantial beads shaped as opium poppy capsules (from the Papaver somniferum plant), decorated with dozens of turquoise-inlaid poppy flowerheads. She also wore a large brooch shaped as a poppy flower and owned what appears to be an incense burner decorated with a poppy. This highest status female owned the most significant objects with poppy imagery, while three of the four other women also wore jewellery and appliqués enhanced with similar poppy ornament, including brooches and beads stitched onto clothing. Neither the warrior nor the junior woman had possessions decorated with opium poppies.

The ancestral origin of these Tillya-tepe people was among the pastoral tribes occupying the steppe-lands of eastern Eurasia, extending from the north Pontic and Caspian areas in the west, across Central Asia and as far as Siberia and Mongolia in the east. There is archaeological evidence for the use of opium among these cultures, as well as other psychoactive substances such as cannabis (Cannabis sativa)and ephedra (Ephedra spp.) the source of ephedrine, suggesting that such drugs played an important role in these nomadic communities.

Opium gets a bad press these days, and yet we know from Dioscorides and Pliny, more-or-less contemporaries of the Tillya-tepe people, that its beneficial properties were well-understood in antiquity. Opium was used to cure many ills, being especially valued for its capacity to relieve pain and to procure sleep. However, the dangers of opium were also recognised, and it was regarded as a poison if used in excess. Throughout the history of mankind, plant-based remedies have dominated medicine. Indeed, the paramount role of plant medicine continues today among those societies for whom modern synthetic remedies are either unavailable, or too expensive, or are seen as undesirable. In addition, in the past opium certainly played a role inmagico-religious rituals, particularly those relating to death – an association which may be connected with opium’s ability to soothe the grief of mourners, or, in extremis, its capacity to induce death.

So, with this information in mind, we return to the four Tillya-tepe women whose possessions were decorated with opium poppy iconography. These women were buried with caches of small vessels and implements, including knives, and it is postulated that these items were ‘tools of their trade’, related to activities involving opium. Perhaps they handled opium in some professional capacity, since such life-saving or life-destroying drugs were often retained under the aegis of elite women, who understood the social value and dangerous potential of plant knowledge. In light of the common association of cult and healing in pre-industrial societies, medical remedies might be combined with religious rituals for optimum efficacy. Do the Chinese mirrors, carefully laid on their chests, imply some sort of apparatus used for divination? If so, perhaps we could view them as priestesses, performing a societal role as figures with medical and religious authority, controlling the use of opium for pharmacological, funerary and cultic activities, thus giving these women power over life and death.

Afghanistan is the journal of The American Institute of Afghanistan Studies, dedicated to the cross-cultural study of Afghanistan and its surrounding regions, delving into its rich history from a wide variety of humanities-focused angles. The journal covers all subjects in the humanities including: history, art, archaeology, architecture, geography, numismatics, literature, religion, social sciences and contemporary issues from the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods. Read more articles from the journal, find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.