By Jemma Stewart

H. Rider Haggard’s Gothic Garden

In the Gothic Studies articles ‘Blooming Marvel’ and ‘She shook her heavy tresses’, I assess the ways in which floral symbolism (or floriography) in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and H. Rider Haggard’s She (1886-7) has been adapted from a distinctly masculine-Gothic perspective to influence the narrative direction of the texts. The garlic flower of Dracula and perfume within She are intertwined with the femmes fatales of these works – Lucy Westenra and Ayesha, respectively. Floriography is not limited to these two novels within the oeuvres of Stoker and Haggard – we may find further examples of floriography in Haggard’s Cleopatra (1889) where the rose, lotus, poppy and pomegranate contribute to creating a poisonous dramatic setting. The ‘gothic aesthetic’ created through the mummy’s curse narrative is enhanced by a garden of poisonous floriography.[i] This ‘gothic aesthetic’ is not just a subjective imposition, a case of reading the text through a gothic lens, but integral to Haggard’s reimagining of the narrative of Antony and Cleopatra.[ii] Floriography is not necessarily solely connected to a femme fatale but has wider implications relating to the tone, style and construction of the world of the novel – the duplicity, betrayal, tragedy and atmosphere of decay and death which run throughout the story of Haggard’s Cleopatra. Floral symbolism is more common in Victorian fictions than we might assume, and it is rarely used arbitrarily. This, I believe, is connected to the cultural impact of the language of flowers, which had its roots at the beginning of the nineteenth century and remained in circulation at the fin de siècle when Haggard and Stoker were writing.

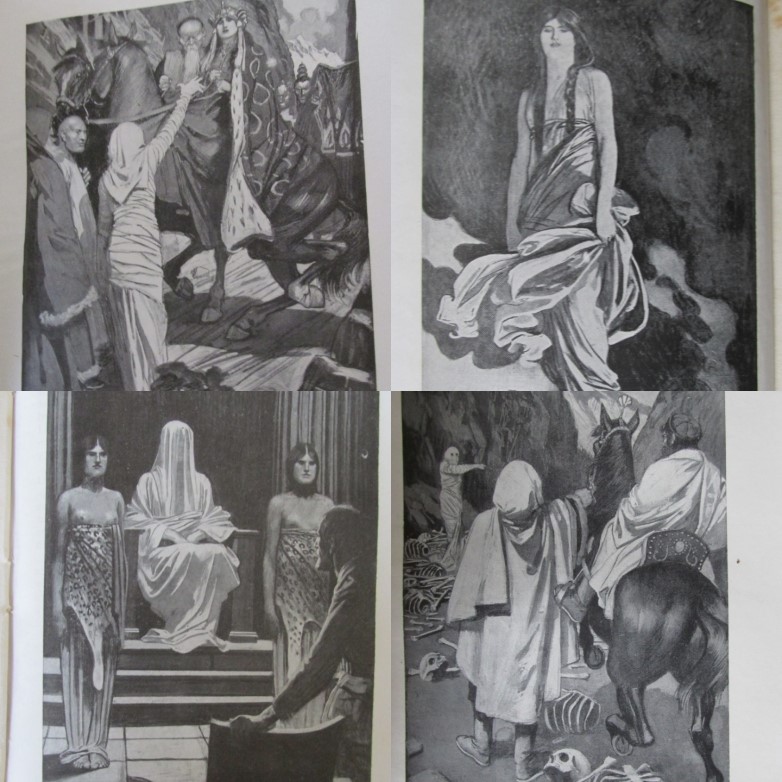

‘She grew white and silent as the corpse upon the bier behind her.’, Maurice Greiffenhagen in H. Rider Haggard, Ayesha: The Return of She (London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1905), p. 183.

‘There, on the point of the pillar, stood Ayesha herself!’, Maurice Greiffenhagen in H. Rider Haggard, She and Allan (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1921), Frontispiece.

‘It rose, it stood up, a human figure.’ Maurice Greiffenhagen in H. Rider Haggard, Ayesha: The Return of She (London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1905), p. 206.

‘There she sat, straight and still, and clothed in shining white and veiled’, Maurice Greiffenhagen in H. Rider Haggard, She and Allan (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1921), p. 142.

The poisonous flowers of Cleopatra (1889)

Contemporary reviewers saw parallels between the stories of Ayesha and Cleopatra, suggesting that ‘We have in both the supreme figure of a woman as centrepiece and pivot’,[iv] and ‘females of weird powers’[v] prove a repetitive plot device. Whilst we may think of Ayesha as a more traditional gothic icon within the ‘Imperial Gothic’, there is plenty of gothic imagery within Haggard’s historical romance Cleopatra and it is enhanced by his use of floriography.[vi] One nineteenth-century reviewer highlights the poisoned atmosphere of the tale within this reimagining:

The hero’s expiation, during years of ascetic penance, final vengeance in the preparation of the poison by which, instead of the traditional asp, Cleopatra dies, and eventual confession and sentence by his brother-priests, form a sombre closing act to this drama of treachery and crime. [vii]

[…] and though I bore no ill-will against Antony, yet he must fall, and in that fall drag down the woman who, like some poisonous plant, had twined herself about his giant strength till it choked and mouldered in her embrace.[viii]

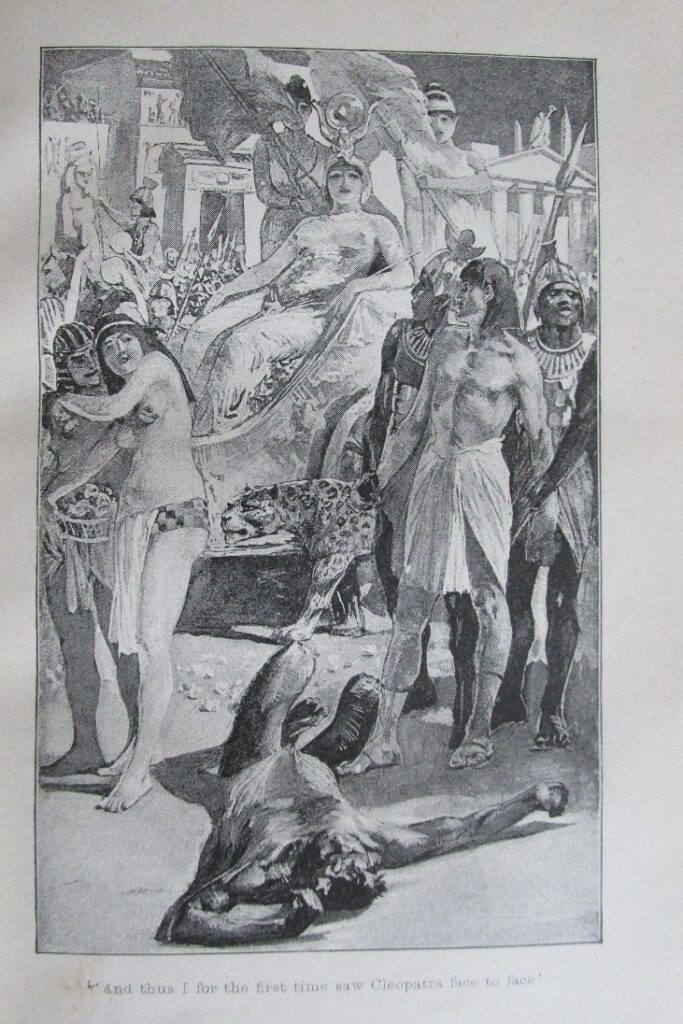

Cleopatra, with eyes ‘hued like the Cyprian violet’ (90), is one of Rider Haggard’s femme fatales. She is shrouded in scent throughout the story, reflecting the true use of perfumes in Ancient Egypt as well as her status as an enduring icon in the cultural imagination. Described as ‘this wanton squandering the wealth of Egypt in chariots and perfumes’ (92); the ‘Perfume came from her hair and robes’ (146); her ‘perfumed breath’ (152); and, her ‘perfumed chamber’ (145). Jack Goody elaborates on the use of perfume in Ancient Egypt:

Odour was an important constituent of the culture of the toilette and this feature of flowers could be conserved even if their appearance could endure only in dried form.[ix]

Being concerned about the physical perpetuation of the body as a condition of eternal life, the Egyptians developed the art of embalming. For treating the dead, as for treating the gods and the living, they needed unguents, incense and perfume, partly to create pleasant odours to combat the foul stenches but more importantly to please the recipients. The trade in spices and aromatics, which was later taken up by Rome, was of fundamental importance to the country. (Goody, p. 43)

But Haggard’s floriography doesn’t end with perfume– in fact he cultivates a veritable poisonous garden for his historical romance, employing his extensive knowledge of Ancient Egypt and distorting traditional meanings within the language of flowers to enhance the tragic mood, to function as portents of doom, to ensnare or trick protagonists or antagonists accordingly. Cleopatra herself is a connoisseur of poisons. The idea that this femme fatale tests a series of poisons for their effectiveness on unwitting slaves, watching their slow demise in order to create a perfect death for herself is particularly macabre; ‘“I have caused six different poisons to be given to these slaves and with an attentive eye have watched their working”’ (296).

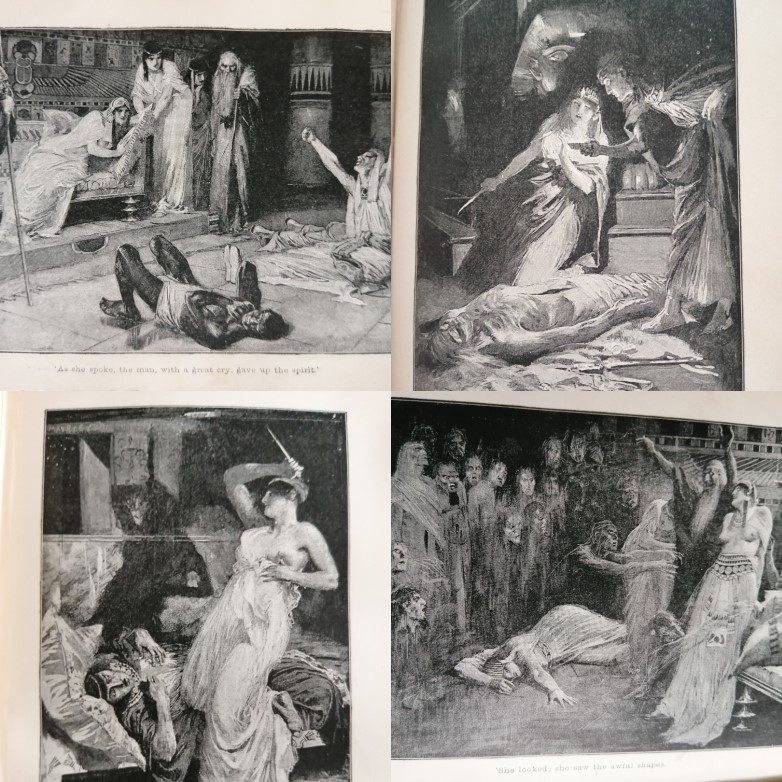

‘As she spoke, the man, with a great cry, gave up the spirit’, Maurice Greiffenhagen (296).

‘She held it up to the light and gave a little cry’, Maurice Greiffenhagen (188).

‘She looked, she saw the awful shapes’, Maurice Greiffenhagen (323).

‘“I’ve won,” she cried’, Maurice Greiffenhagen (152).

Move on to Part 2 of this article.

[i] Karl Bell, ‘Gothicizing Victorian Folklore: Spring-heeled Jack and the Enacted Gothic’, Gothic Studies 22:1 (2020), pp. 14-30 (pp. 26-7).

Roger Luckhurst, The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[ii] Alexandra Warwick, ‘Feeling Gothicky?’, Gothic Studies 9: 1 (2007), pp. 5-15 (p. 7).

[iii] Patrick Brantlinger, ‘Mummy Love: H. Rider Haggard and Racial Archaeology’, in Taming Cannibals: Race and the Victorians (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2011), pp. 159-179.

[iv] Anon., ‘Cleopatra’, Sporting Gazette, 30 November 1889, p. 3.

[v] Anon., ‘Critical Notices: Cleopatra’, Time, 10 October 1889, pp. 446-47 (p. 447).

[vi] Patrick Brantlinger, ‘Imperial Gothic’ in Andrew Smith and William Hughes (eds.), The Victorian Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), pp. 202-216.

[vii] Anon, ‘Notes on Novels: Cleopatra’, Dublin Review, 22 October 1889, pp. 441-41 (p. 442).

[viii] H. Rider Haggard, Cleopatra: Being an account of the fall and vengeance of Harmachis, the Royal Egyptian, as set forth by his own hand, New Edn. (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1891), p. 300. All other references refer to this edition – page numbers in brackets.

[ix] Jack Goody, ‘In the beginning: gardens and paradise, garlands and sacrifice’ in The Culture of Flowers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 28-72 (p. 38).

Gothic Studies is the journal of the International Gothic Association, and covers the field of Gothic studies from the eighteenth century to the present day, providing an international platform for dialogue and cultural criticism in the sphere of Gothic from within every period and media form. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.