I first encountered Jean-François Lyotard’s work in the mid-1980s, after the publication of the English translation of his book The Postmodern Condition. It was a text that created quite a stir in the English-speaking academic world, drawing a lot of both praise and criticism. I was one of those to be critical, as in the first thing I ever wrote about Lyotard, a journal article for Radical Philosophy, where I argued there was a nihilistic quality to his thought.

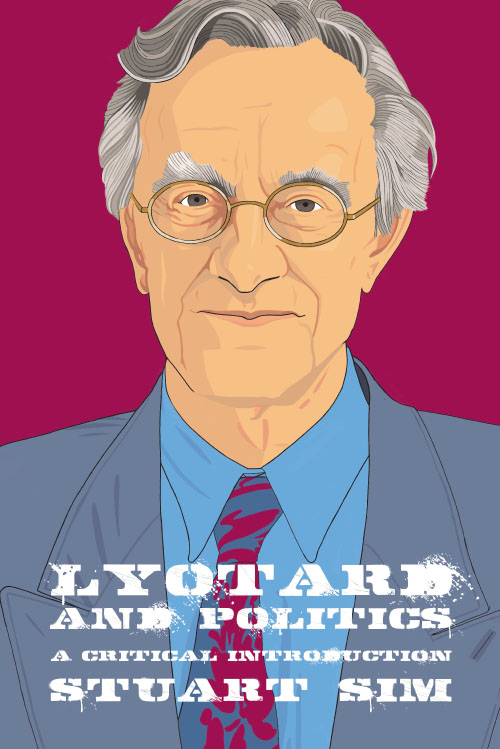

The success of The Postmodern Condition sparked the translation over the next few years of several other works by Lyotard, which revealed a much more complex, subversive and wide-ranging thinker than The Postmodern Condition alone suggested. By the point I went on to write a monograph on him in 1996, I was much more sympathetic towards his work and I have continued to be so ever since, editing The Lyotard Dictionary for EUP (2011) before my new study of him for the ‘Thinking Politics’ series, Lyotard and Politics. I now consider Lyotard to be a major voice in the history of scepticism, one we can learn much from in our troubled times.

Lyotard v Marxism

The book’s title says it all: Lyotard is an intensely political thinker, whose commitment is apparent throughout his very substantial body of writings. Here is someone who engaged with Marxism, colonialism, fascism, Judaism, the 1968 événements, cybernetics, the death of the sun, modern and postmodern art, film, literature, music and much more, always with a keenly political eye and sceptical attitude. He was undeniably one of the most politically oriented thinkers of his age and that is what I am out to convey in Lyotard and Politics, which ranges over his major works and their wide variety of topics, with a particular interest in Lyotard’s turn away from Marxism.

Lyotard is one of the most provocative of the generation of post-Marxist theorists who emerged in the later decades of the twentieth century – as his blisteringly hostile attack on Marx in Libidinal Economy demonstrates. His work in this area still has considerable resonance in our contemporary situation, where the left is struggling to make its voice heard in a world turning increasingly to the right – and more worryingly, the extreme right – in ideological terms.

Little Narrative v Grand Narrative

Lyotard’s concept of the ‘little narrative’ remains one of his most important contributions to political debate, urging us to resist the appeal of the ‘grand narratives’, or universal theories, of our culture and fight injustice in a deliberately small-scale, targeted way. Little narratives are expressly designed for the short term. The objective is to prevent any of them developing into a full-blown ideological grand narrative that then becomes as authoritarian and restrictive of individual creativity and ingenuity as its rival counterparts (and they are to be found from politics and religion right through to the arts and humanities). Lyotard’s dislike for all-explanatory theories is a constant over his career, from his early unease about what lay behind Algeria’s revolutionary struggle against French colonialism, to his anger about the conduct of the French Communist Party during the événements, and then his rather apocalyptic vision of the dangers posed by the rise of techno-capitalism in the later stages of his life.

Lyotard himself avoids putting forward his own grand narrative, proposing instead a flexible ‘philosophical politics’ which strives to defend difference and diversity whenever and wherever it is being suppressed. Those philosophers who defend grand narratives (mere ‘intellectuals’ as he dismisses them) are betraying their discipline, using it to reinforce the hold that the powerful exert over the rest of us. Lyotard maintains a staunchly anti-authoritarian stance as a thinker, being perpetually on his guard against any possibility of turning into a mere ‘intellectual’.

Lyotard and the Arts

Lyotard had a lifelong fascination with the arts, particularly painting, and that is another central concern of the study. The arts were clearly a major source of inspiration to him, an area where he could test out his political theories, and it is an aspect of his character that deserves to be better known. The breadth of his interests signals a philosopher with a constantly enquiring mind, always ready to tease out the political implications of whatever he is analysing and bringing an innately sceptical sensitivity to the task. Lyotard really needs to be seen as one of the most impressive thinkers of his generation, a philosopher well worth getting to know much better.

About the author

Stuart Sim is a retired Professor of Critical Theory at Northumbria University. He is the author of several works on Jean-François Lyotard, including Jean-François Lyotard (1996) and Lyotard and the Inhuman (2001), and editor of The Lyotard Dictionary (2011). You can find out more about his new book Lyotard and Politics on our website.