Modernists were obsessed with technology, and often made it a feature of their inventive art and writing. But have you ever wondered whether any modernists took the next step, and actually tried their hand at inventing?

In this series of blogs, Eric White introduces some modernists who have, and whom he’s written about in his new book Reading Machines in the Modernist Transatlantic Avant-Gardes, Technology and the Everyday (EUP 2020).

Rose (and Bob) Brown’s Reading Machine

Poetry aficionados, media archaeologists and scholars of modernism might have heard of the ‘godfather of the e-reader’ Bob Brown, and his infamous ‘Reading Machine’ – but his wife Rose is an equally compelling figure. In fact, her story changes how we understand the connections between technological and literary innovation, and their capacity to promote social change – and with one exception, it has remained untold.

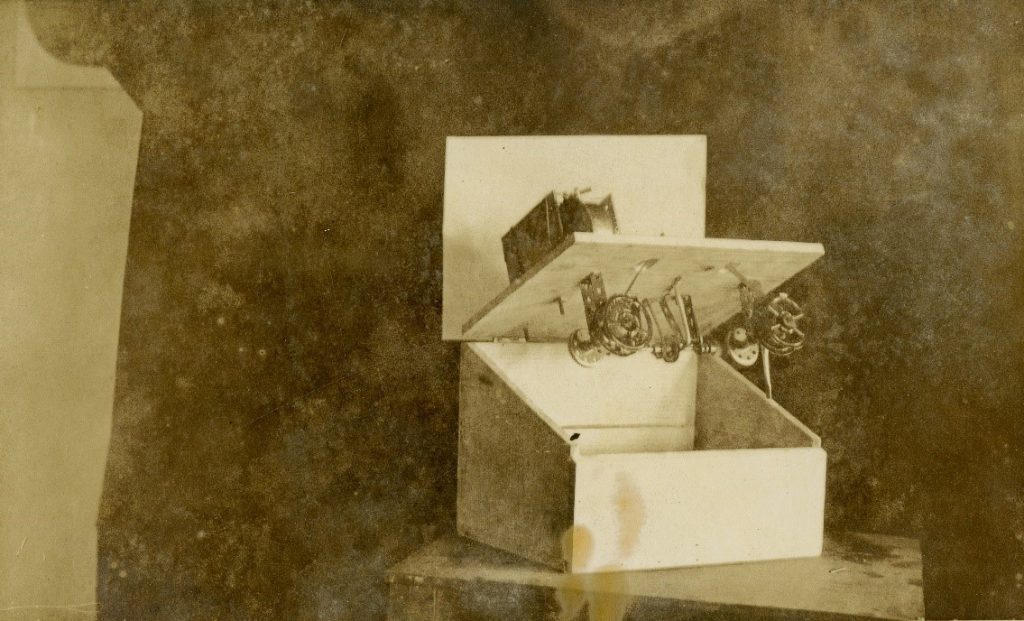

Bob dreamed up his ‘reading machine’ in 1915 while writing imagist poetry and trading shares in Greenwich Village. His invention combined an early form of microfilm technology with new type of writing that he called the ‘readies’ (after the ‘talkies’ in cinema). The result was a single stream of magnified, flamboyant text that looked like Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons in telegraphese read through a stock-market ticker. Bob returned to the invention occasionally in the 1920s, but when he and Rose settled in the expatriate enclave of Cagnes-sur-mer, France in 1929, they invited their modernist friends (including Stein, Alfred Kreymborg, Ezra Pound, and William Carlos Williams) to write samples for this prototype technology.

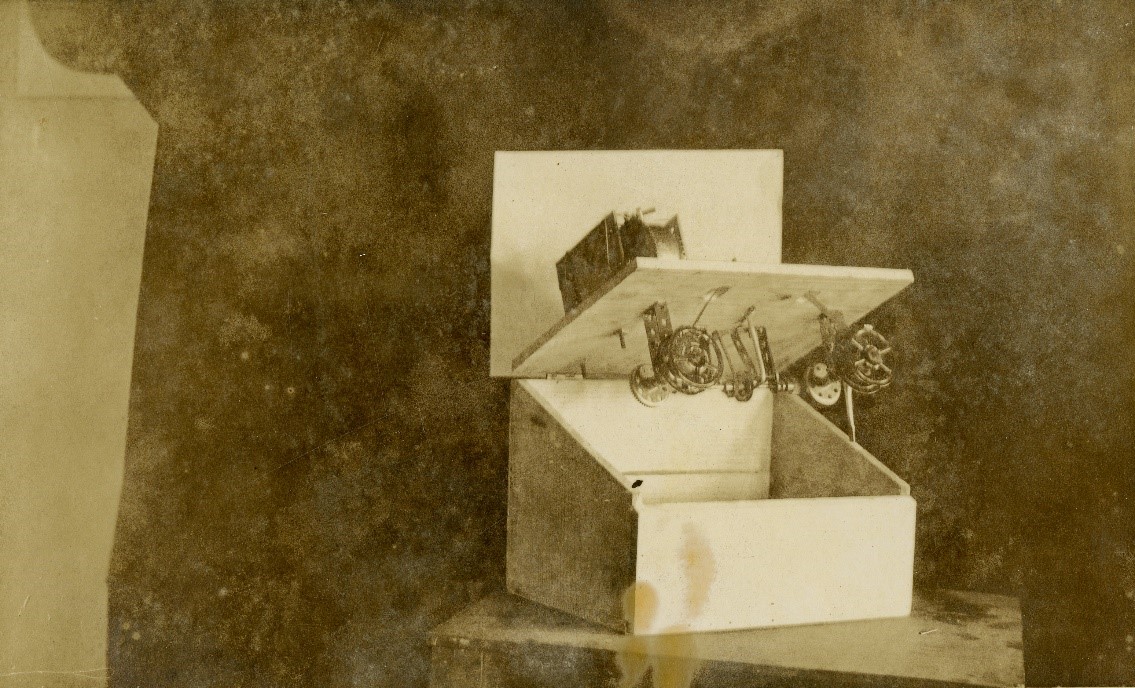

The resulting anthology Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine (Roving Eye Press, 1931) has just been reissued by EUP as a critical facsimile edition, edited by Craig Saper and myself. As well as collection of ‘readies’ by 45 writers, the collection featured a blurry photo of a prototype reading machine built by the American surrealist painter Ross Saunders in summer 1931. However, I discovered a photo in the archives (below) that shows its inner workings in far greater detail. Contrary to the critical consensus, and following some retro-engineering workshops at makerspaces in Oxford, this device almost certainly worked as Bob described.

Despite the surge of interest in Bob’s machine in the early 1930s, critics usually write off the project as one of many avant-garde casualties of the Great Depression.

However, as the archives reveal, this isn’t actually the case.

Transatlantic Reading Machines

Due to the brilliance and hard graft of Rose, another reading machine took shape in America, where the Browns returned after losing their second fortune in the Depression. In all likelihood, by the end of 1932, Rose Brown’s reading machine was very much alive!

Her correspondence describes a compact, battery powered machine that used a ground-glass system to magnify the text. Here are a few forms it may have taken:

the first is an illustration for a commercial prototype included in Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine (above); the second is a 1937 sketch by modernist artist and readies contributor Hilaire Hiler (below):

Bob’s cousin Clare Brackett, who ran the National Machine Products Company (NMPC) in Detroit, gave Rose a semi-functional prototype with working electro-mechanics, but Rose still needed to complete the readies medium and optics. Ingeniously, she and the pioneering lithographer Hugo Knudsen produced a micrographic readie using standard 35 mm nitrate film and an elaborate photo-composition method. As Bob explained in an unpublished essay, ‘Rose made the first moving readie film – – all of [Voltaire’s] Candide [. . .] Rose had it done in one line on Teletype, pasted it on a roll of wall paper and Knudsen photographed it down to invisibility’.

Rose Brown’s Reading Machine and Social Change

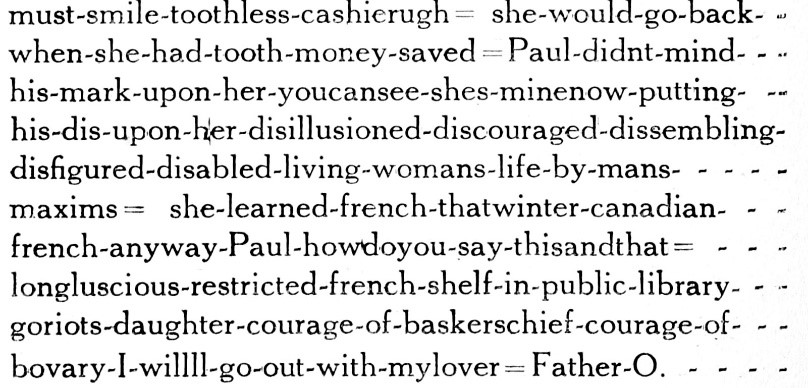

Rose’s choice of Candide had a political resonance in the Great Depression, since Rose and Voltaire both critiqued colonial rule. While in France, Rose launched a new career as a journalist, and wrote on both culinary and political topics, including the 1931 famine in Niger, which was partly caused by the French colonial government’s negligence. Her anthologised ‘readie’ ‘Dis’ also expressed her desire for social change, but by using reading technology and literary experiment rather than political journalism. ‘Dis’ details working-class women’s struggle to survive the daily grind in Hell’s Kitchen. Rose commodifies every aspect of the women’s day in the story. The equals signs tally up the abuses they suffer, but also, their ability to surmount them:

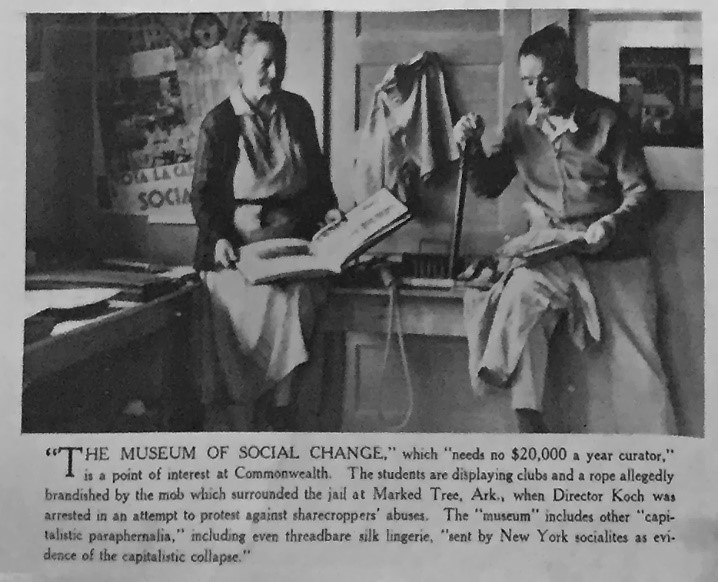

Rose Brown’s reading machine accompanied the Browns on their extraordinary journeys in the mid-1930s, where they wound up as faculty members of Commonwealth College in rural Arkansas. At Commonwealth, the Browns set up the Museum of Social Change, which exposed the insidious effects of industrial capitalism through a dialectical arrangement of objects. The photo below shows Rose holding a scrapbook detailing strikes and civil rights protests organised by Commonwealth College and local sharecroppers.

From Commonwealth, the Browns organised tours to the Soviet Union in 1935-36, where they attempted to develop the reading machine with Moscow Polytechnic Museum. The experiment ended in failure, but when they returned to the US, they resumed their work on the reading machine. In the late-1930s, they tried to develop it with several microfilm concerns, including the ill-fated ‘Optigraph’ consortium. However, the Browns eventually lost the machine and the Candide readie after they travelled to South America in the early 1940s.

Rose died tragically from a sudden illness on the Brown’s plantation in Persepolis, Brazil, in 1952. Bob eventually returned to the US and remarried, but though he continued his literary experiments, he stopped working on the reading machine shortly after Rose’s death. Perhaps this is because he recognised that the idea belonged to Rose just as much as to him. However, as I argue in my book, the idea also belongs to the patchy and incomplete story of inter-war modernism, broadening its scope, muddying its generic boundaries, and presenting a gloriously complex picture of cross-disciplinary innovation.

About the author

Eric White is Senior Lecturer in American Literature at Oxford Brookes University. Originally from Vancouver, Canada, he has taught at the University of Cambridge, Anglia Ruskin University and the University of Edinburgh, and has held fellowships at the Beinecke Library, Yale University, the University of Edinburgh, and the University of Oxford. Eric is PI and co-founder of the Avant-Gardes and Speculative Technology Project, which re-imagines modernists’ inventions using Augmented Reality.