In this five-part series, Geetha Ramanathan, author of Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), explores over a century of African American films and what they tell us about African American history both on and off screen.

African Americans have long sought to narrate their history and themselves in film, to draw out the complexity of African American culture, how it is not homogenous, how it is rich and dense with the hugeness of the universal and narrow and specific with the detail of the particular, and above all, how it bears no resemblance to dominant depictions. Among the African American films that perform this work are:

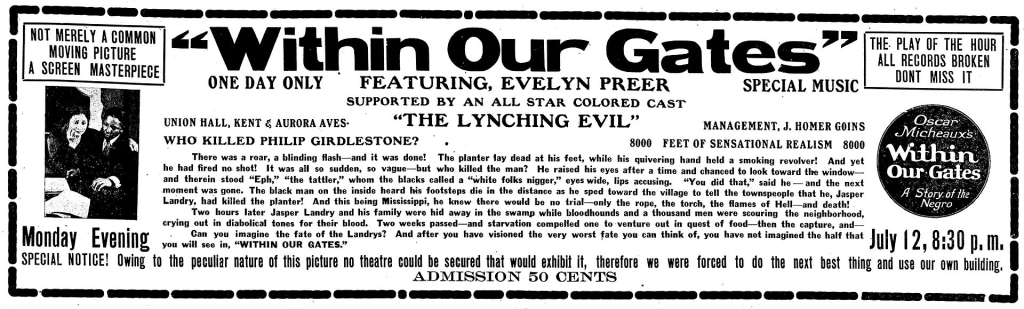

“Within Our Gates” Oscar Micheaux. USA: Micheaux Book and Film Company, 1919

Starting with this film is uncanny; not only does it envision a nation in which African Americans lead the way to a better nation, it also reveals the dark history of lynching in the country, making a brilliant conceptual connection, through the cinematic cut, linking the rape of black women to the lynching of black men. Intended as a response to the infamous Griffith film, “Birth of a Nation,” and absurdly pegged as “history written in lightning” by the then occupant of the White House, the history of the film’s reception and its censorship for fear of “riots” in American cities will seem all too familiar to contemporary audiences.

The story is loosely organised around Alma, who has come up North to seek funding for a school for Black children in the South. Looking at the film’s images of White men, women, and children enjoying the “barbecue” in their town in conjunction with images of state violence and repression makes for an uneasy and difficult scrutiny, forcing us to question Micheaux’s optimistic conclusion. In a recent humanities seminar organised by the University of California, Angela Davis pointed out the central importance of visual imagery in drawing attention to police brutality and racial injustice. Micheaux’s film shows us that there is a century-long history of African American visual artists who have struggled to set the record straight.

“The Scar of Shame” Frank Perugini. USA: Philadelphia Colored Players Film Corporation, 1927

“Race” films as they were known addressed Black audiences who flocked to Black theatres in large numbers. “The Scar of Shame” entertains issues of what was called “caste,” or colour prejudice within the African American community, and its intersection with race.

The film tells the story of a young woman, working in a Black boarding house, who is routinely abused by her stepfather. Rescued by a light-skinned upper class educated Black man boarding there, the protagonist believes she has stepped into the middle-class life, complete with romance. However, her rescuer, a Black Beethoven in the making, refuses to acknowledge her to his mother who wishes him to marry within the set.

The seriousness of the address primarily to a Black audience, shifts the film form decisively away from an exterior perspective on African American society to an interior one. The film’s focus on the female and her dilemma within the community make it among the first feminist films within the larger contexts of race and class in American film history.

“Losing Ground” Kathleen Collins. USA: Kathleen Collins and Ronald K. Gray, 1982

“Losing Ground” similarly explores themes of feminism, race, and class from an interior perspective. The director, among the first film professors in the US, stated that her aim was merely to present the people she knew, the lives that they lead that were largely invisible in the era of blaxploitation films. Collins deliberately veered away from the dominance of the urban background of many African American films and chose to film her work in domestic interiors and in up-state New York, deliberately using the techniques of what could loosely be called Romantic painting. A dramatist herself, her inter-arts approach —drama, painting, film—subtly celebrates the versatility of the African American artist.

The film features the complex desire of a philosophy professor to be both an intellectual and find the ecstatic, a path seemingly foreclosed in western annals. The first feminist film to portray female desire to establish and retain authority as a woman (note that I do not say “as a Black woman”) leads us to philosophical questions on Black femininity and masculinity in US culture. The visual texture of the film points to a different direction in African American films, one that sought richness in the very palette, and sought to give African American audiences pleasure in imagery, as distinct from narrative success, a rare phenomenon in the history of American film. Julie Dash, who worked with Collins in New York, was to be influenced by this aesthetics of “surfeit,” rather than that of paucity.

The films discussed above are available in some regions via the Criterion Channel.

Learn more about the films of Kathleen Collins in Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

About the Author

Geetha Ramanathan is the author of Kathleen Collins: The Black Essai Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2020). She is Professor of Comparative Literature at West Chester University where she teaches Comparative Literature, film and Women’s Studies (including Feminist Film and African American Film). Her interests include modernist, feminist and third world literature.